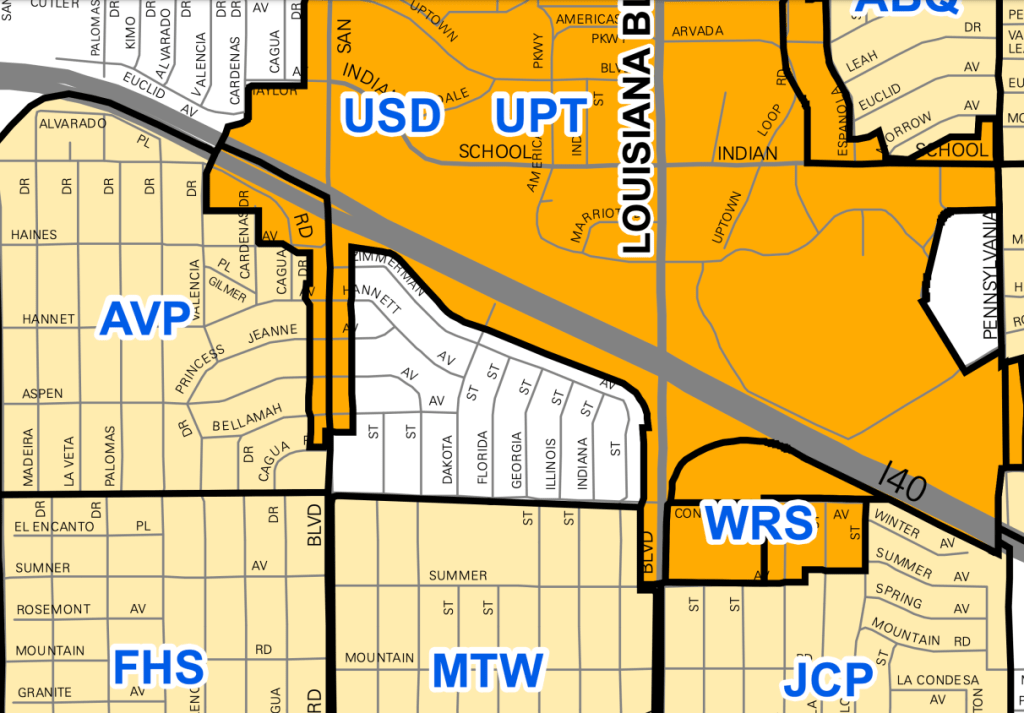

The Mark Twain Neighborhood Association (MTNA) is attempting to expand its boundaries in what can only be described as a strategic land grab to consolidate power and resist zoning changes brought by O-24-69. Their goal? To absorb a neighboring, unaffiliated area and use it as a tool to push back against progress while simultaneously lamenting their own neighborhood’s decline. This contradiction exemplifies a broader issue within Albuquerque’s neighborhood association system, which often resists the very changes necessary for revitalization.

The Fear-Driven Expansion

The special meeting set for March 15 is framed as an effort to strengthen the association’s influence in the wake of “major new challenges” such as “upzoning,” NM Expo redevelopment, and what they call “homeless incursions.” Their language is revealing—this is not about improving the neighborhood for all but about maintaining control and keeping new residents and ideas out. Their attempts to double their membership are not driven by a desire for inclusivity but by a desperate bid to resist inevitable urban change.

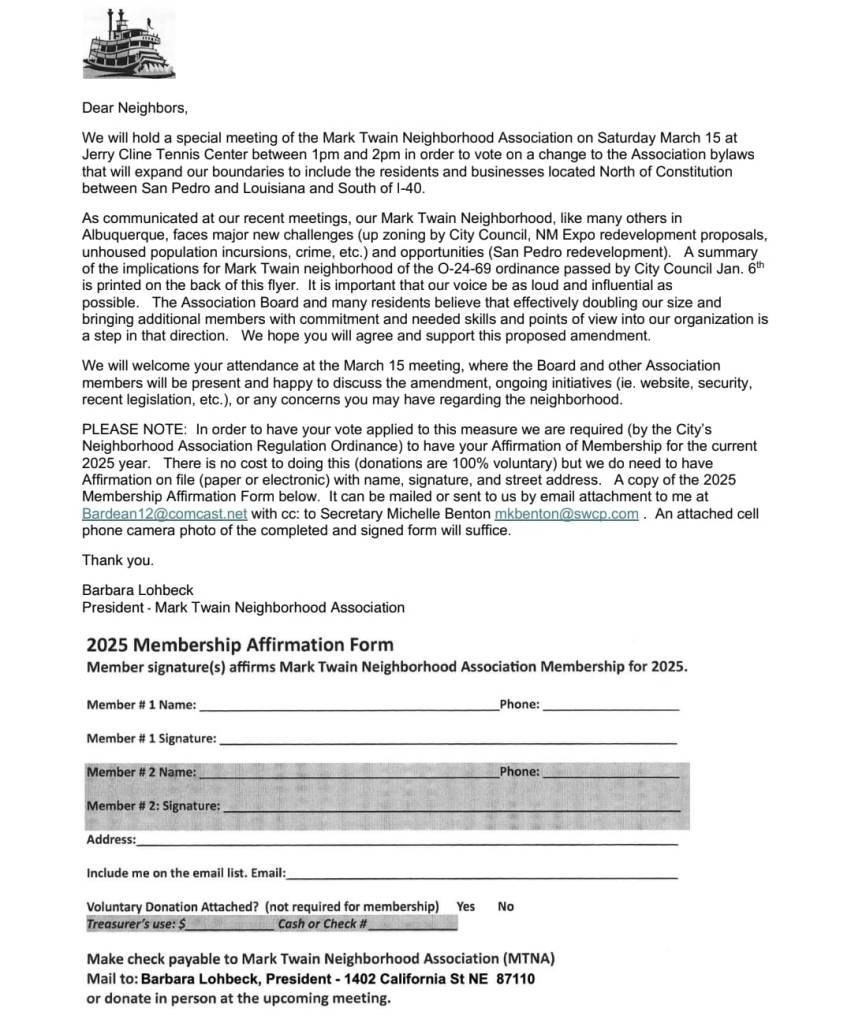

A letter sent to residents lays out the association’s rationale, full of coded language about protecting the neighborhood while simultaneously admitting to its struggles. The notice, which has not been made publicly available online and is difficult to access, highlights the lack of transparency in these decisions. Below is a screenshot of the notice sent to residents (or, “members,” rather):

The Contradictions of NIMBYism

MTNA leadership often voices concerns about disinvestment and neighborhood decline, yet their actions contradict their stated worries by opposing policies that could drive reinvestment and renewal. And yet, when efforts are made to increase density, bring new investment, or improve infrastructure, they respond with aggressive opposition. This contradiction was on full display at the recent NM Expo redevelopment meeting, where some neighborhood leaders loudly denigrated proposed improvements. If they acknowledge their neighborhood is struggling, why are they so committed to blocking revitalization?

The Trumpian Playbook: Fear, Exclusion, and Power Hoarding

The rhetoric coming from MTNA’s leadership mirrors national political fearmongering: portraying change as an existential threat, using dehumanizing language to describe vulnerable populations, and seeking to maintain control by any means necessary. Their president’s reference to homelessness as “homeless incursions” is particularly telling—it frames unhoused people not as community members in need of support but as an invading force to be repelled.

At the same time, MTNA does not even try to hide that this annexation effort is about consolidating power. By expanding their borders, they can artificially boost their influence in city politics, ensuring that their opposition to housing reform carries more weight. They are not interested in solving the problems they complain about; they are interested in maintaining the status quo, even if that means presiding over a neighborhood in decline.

O-24-69 presented a direct challenge to their control. This zoning reform opens the door to more multifamily housing, mixed-use development, and townhomes, breaking the stranglehold of restrictive single-family zoning. Additionally, it requires neighborhood associations like MTNA to engage in good faith, democratic outreach to the communities they claim to represent if they wish to appeal a development project. This is likely why MTNA is so aggressively expanding—if they can artificially inflate their membership now, they can later claim to represent a broader base when trying to block future development.

Ironically, their own notice underscores how selective they are in curating their membership. The notice states that bringing in new residents and perspectives could help strengthen their voice while emphasizing the importance of “committed members.” This language signals that they are not seeking a genuine cross-section of their community but rather filtering for those who align with their predetermined agenda. Their lack of transparency—failing to widely share the notice and with their webpage mysteriously taken down—reinforces that their goal is not to elevate diverse voices in the neighborhood but to suppress them.

This selective participation further exposes the issue of giving these groups disproportionate influence in city government. O-24-69 has already demonstrated widespread public support, with the overwhelming majority of public comments and emails to city council in favor of the change. Yet, neighborhood associations like MTNA leverage their status to exert outsized influence, despite lacking a true democratic mandate. Their focus on “members with commitment” rather than all residents reveals their fundamentally exclusionary nature and highlights the dangers of allowing these organizations to have a privileged role in shaping Albuquerque’s housing and investment policies.

The History of Fear-Based Opposition to Zoning Reform

This kind of reactionary resistance to zoning reform is deeply rooted in America’s history of racial and class exclusion. “Neighborhood character,” a phrase often wielded against lifting bans on new housing, has long been a dog whistle used to justify segregation, exclusionary zoning, and redlining. It is no coincidence that those who most loudly oppose O-24-69 often invoke vague fears of crime, unhoused people, declining property values, and a loss of “community cohesion”—all historically coded ways to argue against housing that would accommodate lower-income and diverse residents.

MTNA’s actions fit into this broader pattern of exclusion. Instead of welcoming new residents and investment, they are attempting to seize more control to prevent change, despite their own frustrations about their neighborhood’s decline. Their fear of O-24-69 is not about genuine concern for the community—it is about maintaining an outdated, exclusionary vision of what their neighborhood should be.

A Path Forward: Addressing Concerns with Real Solutions

Despite their obstructionist tactics, it’s important to recognize that the fears of MTNA members—about disinvestment, rising crime, and neighborhood change—are real. The issue is that their approach to solving these problems is counterproductive, alienating, and exclusionary. Rather than trying to wall off their neighborhood from change, they should embrace the benefits that O-24-69 can bring over time.

- More density means more investment. Increased housing options attract new residents, bringing economic activity and revitalizing struggling commercial corridors like San Pedro.

- Mixed-use development fosters safety. More eyes on the street, more businesses, and more foot traffic help create a safer environment than empty lots and declining homes.

- Neighborhood stability comes from affordability. Young people and families leaving is a direct result of unaffordable housing. Allowing townhomes, multiplexes, and mixed-use buildings helps create a community where residents of all income levels can stay and contribute.

MTNA members, in a sense, are also victims of a flawed system that pits existing homeowners against the future. Rather than bemoaning that their neighborhood was “touched” by O-24-69, they should see it as an opportunity. Many areas of Albuquerque remain burdened by exclusionary zoning that stifles growth, disallows necessary housing, and prevents reinvestment. Being included in O-24-69’s reforms is not a curse—it is a chance to lead the way in revitalization. Instead of fighting change, they could be advocating for how best to use these new tools to improve their community.

A System That Enables Exclusion

This case is not unique—Albuquerque’s Neighborhood Recognition Ordinance grants these groups outsized influence while lacking real democratic accountability. Their meetings are often difficult to find information about (this special meeting, for example, is not listed online, and their city website link is broken), and they function more as private clubs for longtime homeowners than as representative bodies for entire communities. The structure of these associations allows them to punch far above their weight in shaping city policy while shutting out renters, young people, and lower-income residents.

Crucially, the residents of the unaffiliated area that MTNA seeks to annex have not petitioned for representation. Neighborhood associations often claim that they exist to bring communities together, to provide an opt-in system for civic engagement, and to represent the voices of their neighborhoods. However, this attempt to expand is not coming from residents seeking inclusion—it is coming from an established association looking to solidify its power. Instead of fostering organic community participation, MTNA is attempting an undemocratic expansion that further illustrates the need for reform in how neighborhood associations operate in Albuquerque.

This type of land grab has been seen before in Albuquerque, and it played a role in the demise of previous neighborhood recognition systems. If Albuquerque does not want history to repeat itself, the city’s Neighborhood Recognition Ordinance must be reformed to ensure that representation is democratic, that petitions for neighborhood association inclusion originate organically, and that expansions of this nature are barred.

Exposing the Flaws, Pushing for Change

MTNA’s actions highlight the urgent need for reform. While previous discussions about neighborhood association overreach have focused on Seattle’s successful efforts to curb NIMBY power, this case provides a local, real-time example of why Albuquerque must take similar steps.

Neighborhood associations should not have unchecked power to block housing, hoard influence, and use exclusionary tactics to prevent necessary change. At the very least, transparency must be improved—meeting notices should be publicly accessible, leadership structures should be more democratic, and their role in city planning should be re-evaluated to ensure they are not merely obstructing progress — and needed homes.

With neighborhood associations under increasing scrutiny in New Mexico and across the country, some cities have abolished them altogether due to their obstructionist tendencies. Rather than resisting change, advocates within these groups should consider how to be better stewards of their influence. There are neighborhood associations in Albuquerque doing the hard work of outreach and resident representation—why not learn from them? As of now, they are alienating people that could be allies in other areas and contributing to the problems that are putting them under the microscope for the first time. The question is: what path will neighborhoods that function like Mark Twain take?

Mark Twain, the man, spent much of his career satirizing greed, corruption, and exclusionary power structures. It is bitterly ironic that a neighborhood bearing his name is now engaged in the very behavior he would have ridiculed. If Albuquerque truly wants to build a more inclusive and thriving future, it must recognize neighborhood associations that operate like MTNA for what they are: barriers to progress that serve a select few at the expense of the many.

Addendum: What you can do

Contact your City Councilor today and ask them to support amendments to the ordinance that:

- Bar land-grabs like this one from occurring now or in the future

- Require all neighborhood associations to comply with open meetings laws.

- Mandate transparency in leadership, outreach, and decision-making.

- Urge city officials to create new, democratic public input processes that reach Burqueños where we are and that represent us – not just wealthier, older coalition and association members.

Let’s make Albuquerque a city that represents all its residents—not just a vocal few.

Contact your councilor:

District 1 – Louie Sanchez

Email: lsanchez@cabq.gov

District 2 – Joaquín Baca

Email: joaquinbaca@cabq.gov

District 3 – Klarissa J. Peña

Email: klarissapena@cabq.gov

District 4 – Brook Bassan

Email: bbassan@cabq.gov

District 5 – Dan Lewis

Email: danlewis@cabq.gov

District 6 – Nichole Rogers

Email: nrogers@cabq.gov

District 7 – Tammy Fiebelkorn

Email: tammyfiebelkorn@cabq.gov

District 8 – Dan Champine

Email: dchampine@cabq.gov

District 9 – Renée Grout

Email: rgrout@cabq.gov

Leave a comment