How Las Cruces’s Bold Zoning Reform Helps Us Envision Albuquerque’s Future

In a quiet but transformative move, Las Cruces just passed one of the most progressive zoning reforms in the United States.

While it hasn’t (yet) made national headlines, Realize Las Cruces has been making waves in New Mexico’s urbanist circles—and for good reason. Passed in February 2025 and upheld this month after a failed NIMBY-led petition effort, the reform replaces decades of exclusionary, inflexible zoning with a character-based system rooted in organic growth, mixed-use neighborhoods, and walkable urban design.

As we noted in our original coverage (“Las Cruces Just Beat the NIMBYs. New Mexico Should Take Notes.”), the Realize Las Cruces overhaul is more than a local planning update—it’s a template for how cities across New Mexico, and the country, can build a future grounded in flexibility, equity, and sustainability. Where traditional zoning codes stifle creativity and restrict housing to protect the status quo, Realize Las Cruces unlocks possibility.

It simplifies development rules into clear, intuitive categories based on the context of a place—rural, suburban, or urban—and allows communities to evolve naturally in response to changing needs. It legalizes middle housing, corner stores, and entrepreneurship. It prioritizes walkability and transit in urban centers and strikes a healthy balance for mobility in suburban areas. And it does all of this while embracing the complexity and diversity of real neighborhoods.

This piece explores the DNA of Realize Las Cruces—and asks: What would a “Realize Albuquerque” look like?

We’ve already started sketching the map. Now it’s time to see how this framework, so successful in Las Cruces, could serve as a guide to reshape Albuquerque’s future—from Downtown to the Westside, from UNM to Cottonwood, and beyond.

What Realize Las Cruces Does

Realize Las Cruces replaces a fractured, outdated zoning code with a streamlined, character-based framework that reflects how people actually experience place: as rural, suburban, or urban. It’s not just what this ordinance allows—it’s how clearly it communicates it. Zoning is laid out in an intuitive table: three character areas, three residential districts (NH-1 to NH-3), and three density tiers—low, medium, and high. The result is a zoning system that is accessible, transparent, and future-ready.

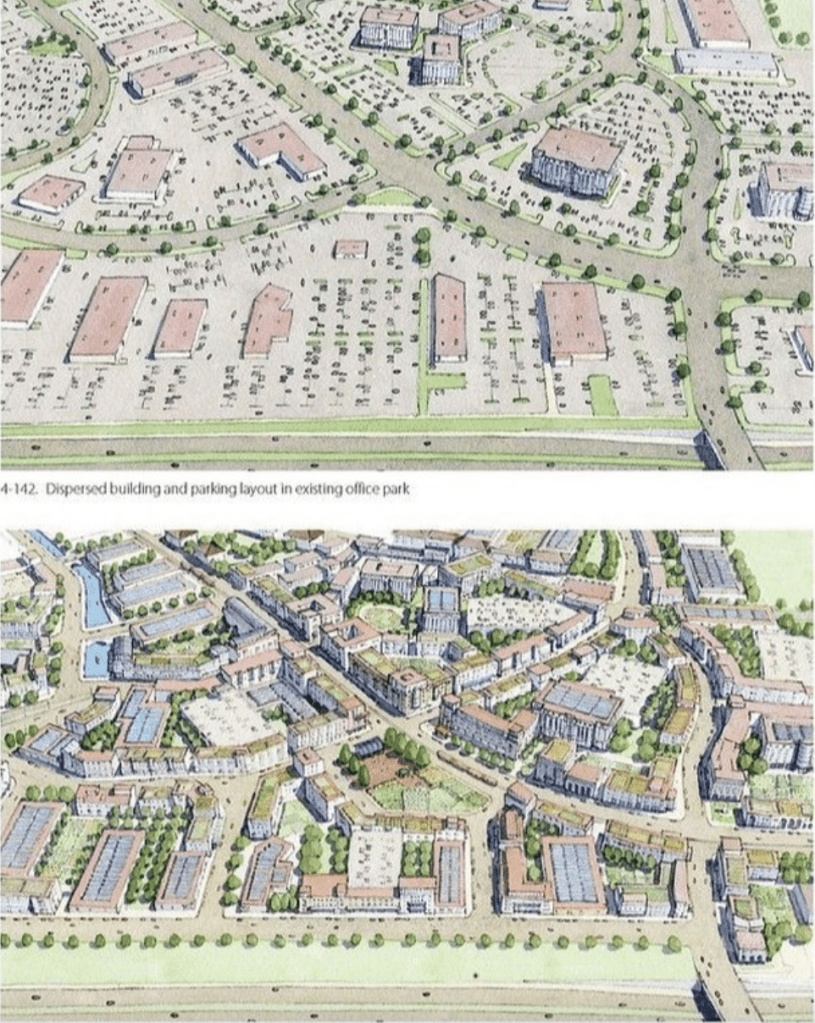

The Suburban Character Area covers the familiar landscape of residential neighborhoods, commercial corridors, and light industrial clusters. These areas, as defined by the code, contain “contemporary development where land uses are dispersed among distinct neighborhoods, retail centers, and office parks.” But unlike many zoning schemes that treat suburban areas as static or car-bound, Realize Las Cruces acknowledges the importance of mobility. It explicitly considers the needs of drivers, pedestrians, cyclists, and transit users—signaling a shift toward more equitable suburban planning. Crucially, it permits incremental density: in a typical suburban context, a ¼-acre lot can now host a fourplex by-right. That small shift alone legalizes an enormous amount of attainable housing, while preserving the underlying scale and character of neighborhoods. It also opens the door for new local nodes to emerge organically, supported by small-scale retail and everyday services.

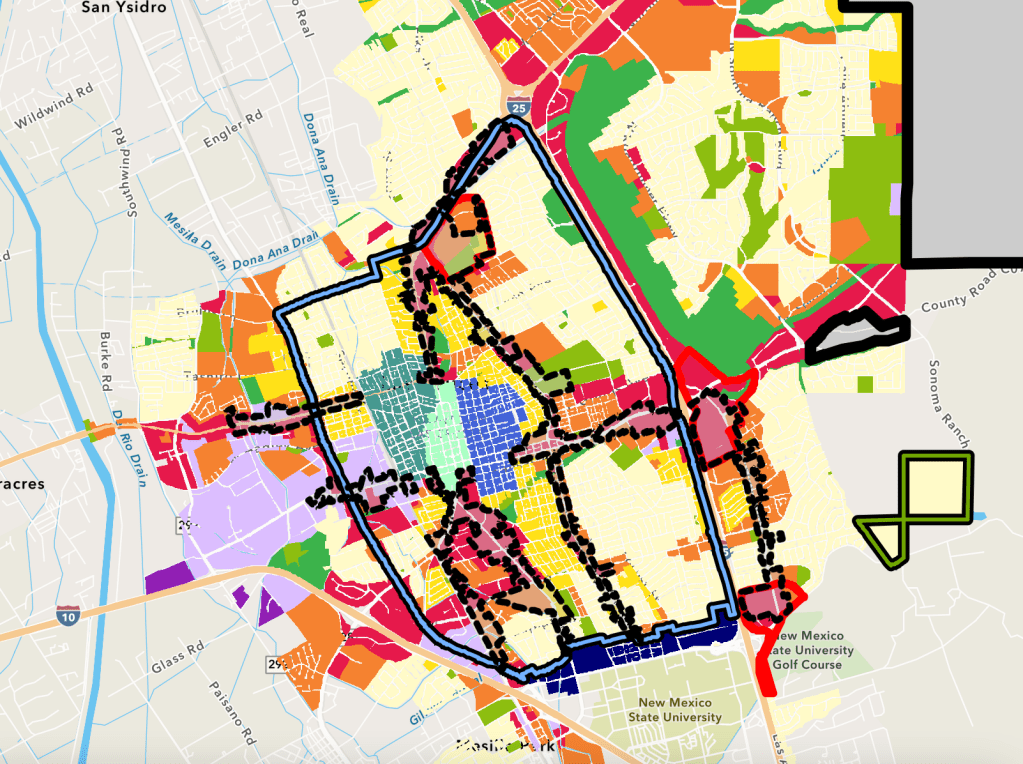

The Urban Character Area reflects the city’s denser cores, including Downtown and center-city neighborhoods (Outlined in the zoning map below). In these areas, the code calls for compact, walkable development and prioritizes the needs of people—not just cars. By design, urban areas under Realize Las Cruces support apartment buildings, vertical mixed use, and small-scale retail, all by-right. The code also reduces or eliminates parking minimums in many urban contexts, enabling buildings to be shaped around their surroundings and users, not outdated formulas. Transit, walkability, and human-scaled infrastructure aren’t afterthoughts—they’re central pillars.

This flexible and context-sensitive approach marks a sharp departure from the rigidity of traditional zoning. For decades, zoning codes have artificially segmented land use and prevented neighborhoods from evolving. They’ve outlawed the very patterns that define great places—mixed-use blocks, gradual density increases, neighborhood retail. Realize Las Cruces reverses that logic.

Its three neighborhood districts reinforce that principle:

- NH-1 focuses on residential use, scaling from 2 units per acre in rural areas to 40 in urban areas. Imagine a home with a casita at the low-end, and a small courtyard apartment with 8-10 units at the high end.

- NH-2 encourages horizontal and vertical mixed use, allowing for services and housing to co-locate—with up to 50 units per acre in urban zones.

- NH-3 is a transitional district, designed to blend retail, office, and housing while maintaining compatibility with adjacent neighborhoods, and allows up to 60 units per acre.

As density increases, so too does the flexibility of allowed uses. Small daycares, workshops, and cafes are legal in most residential zones. Mixed-use apartments and corner stores are allowed without needing a hearing, a variance, or a political fight in many urban areas. This system doesn’t just legalize housing—it restores the possibility of neighborhood life.

By foregrounding how people move through space and how communities change over time, Realize Las Cruces positions itself not just as a zoning reform, but as a civic design tool. It brings land use, transportation, housing, and economic development into alignment—something few zoning documents ever manage.

Las Cruces didn’t just modernize its zoning code. It created a flexible, humane framework for how a city can grow—and grow well and equitably.

What Realize Las Cruces Didn’t Do—and Why That Matters

One of the most impressive things about Realize Las Cruces isn’t just what it changed—it’s what it didn’t include. The reform didn’t lean into popular-sounding policies that, in practice, have been shown to backfire. Chief among them: inclusionary zoning mandates.

While the phrase “inclusionary zoning” sounds like a win for equity, cities across the country are learning hard lessons about the unintended consequences of these policies. Portland, Maine, offers a cautionary tale. After a 2020 referendum led by that city’s Democratic Socialists of America chapter imposed sweeping inclusionary requirements, housing production, or at least permitting, collapsed. According to the city’s own analysis, Portland permitted 941 units (84 affordable) in 2021—before the new rules. By 2023, that number had fallen to just 18 units—none of them affordable. Debate there is intense, as the city is now seeing permitted units come on line, stating that housing production has reached a “new high,” while detractors point to the plummeting permits to show that trouble is on the horizon as the effects of the ordinance begin to be felt.

However, Las Cruces chose a different path: real inclusion through legalization. By opening the door to diverse housing types—casitas, townhomes, fourplexes, apartments—the city is enabling a broader mix of income levels to access neighborhoods that were previously off-limits. Instead of rationing affordability through a small, set-aside percentage of wait-listed units, Las Cruces expanded the overall housing supply—creating more options, more competition, and more price points across the board.

When it comes to subsidized affordable housing, zoning reform is one of the most effective tools cities have. In Austin, Texas, a 2025 study found that the city now leads the nation in affordable housing production—not because of inclusionary zoning, but because of a streamlined permitting and zoning framework paired with targeted tax incentives for nonprofit and mission-driven developers (source). As that study notes, when affordable housing already faces slim margins, a slow, restrictive process can kill projects before they even begin. Las Cruces avoided that trap and made space for mission-aligned developers to succeed.

There is, however, one item on the reform wishlist that Las Cruces didn’t fully check off: abolishing parking minimums. That said, the city significantly reduced or eliminated them in many places—especially within the Urban Character Areas. And that alone is a huge step. Parking requirements have long distorted urban form, raised development costs, and stifled walkable design. By dialing them back, Las Cruces has made room for more flexible, sustainable, and human-scaled development.

In short, Realize Las Cruces didn’t settle for symbolic wins. It pursued structural ones. And it succeeded.

Realize Albuquerque: A Vision Forward

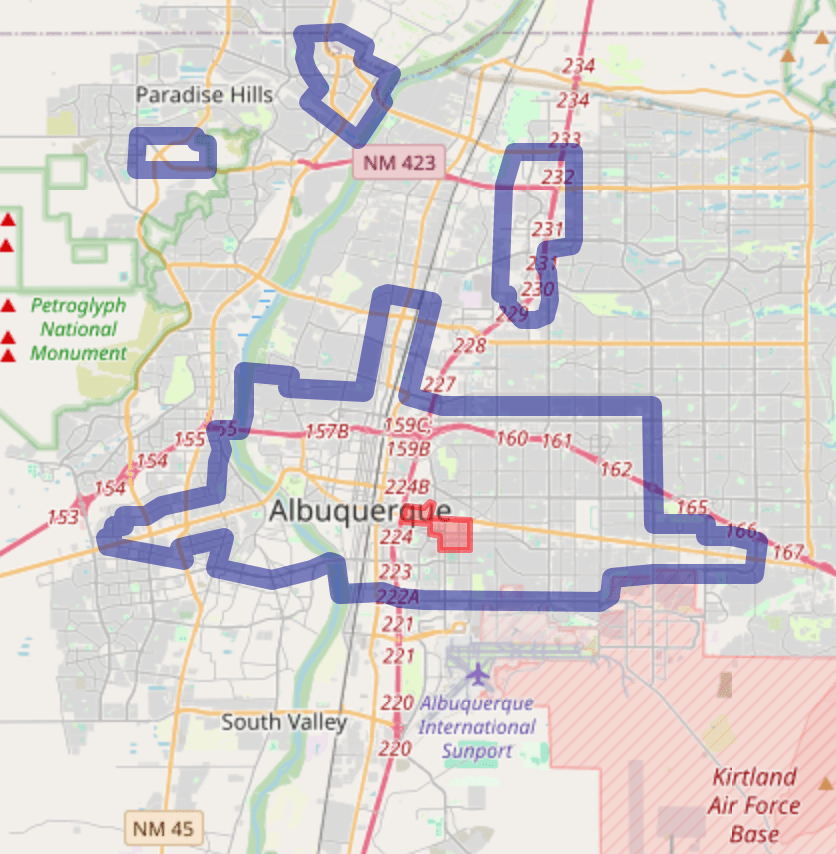

So what would a “Realize Albuquerque” actually look like?

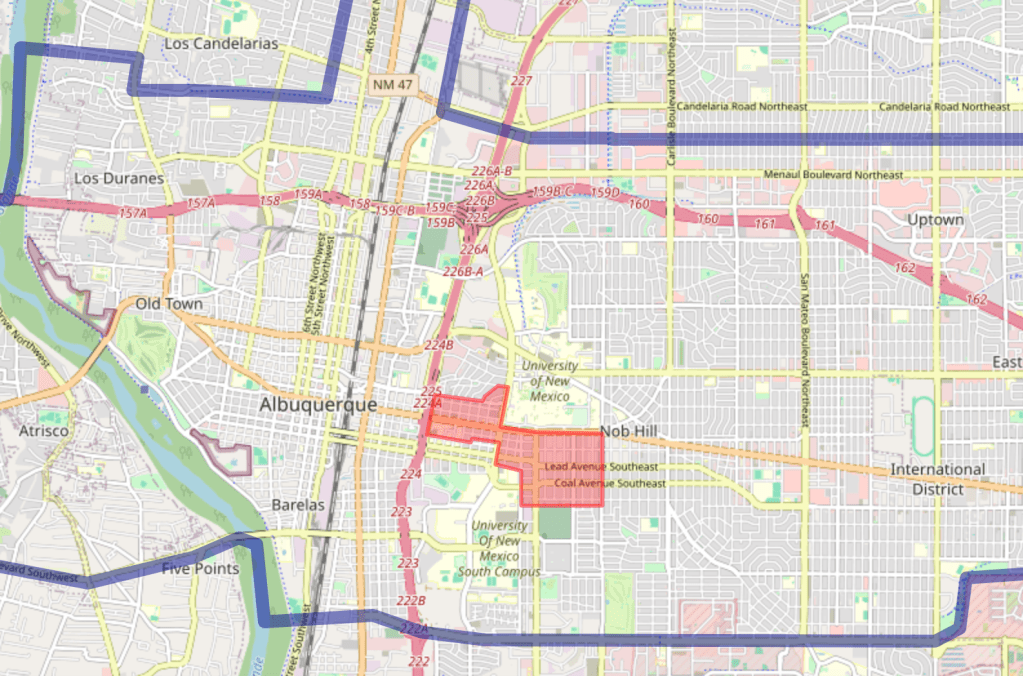

Start at the heart: a re-zoned, revitalized Central Albuquerque, where small apartment buildings, cafés, casitas, and corner stores are legal again. Where neighborhoods like Nob Hill and UNM don’t shrink with each census count but grow, filled with students, teachers, professors, health workers, and families. Where the bones of great urbanism already exist, and we finally let them breathe. Liberating them from exclusionary and arbitrary rules like the “neighborhood edge,” parking minimums, and suffocating height limits.

Within this core, the area around UNM deserves its own special treatment—a high-density, mixed-use designation that recognizes the gravity of this institutional anchor. UNM is not just a university; it’s the heart of a regional education and medical hub, flanked by Presbyterian Hospital, Lovelace Medical Center, and a future developments on both the North and South Campuses. Like University City in Philadelphia or the neighborhoods around the University of Southern California in Los Angeles, Albuquerque can leverage its flagship campus to create a thriving urban district. That means housing for students, faculty, and health workers. Shops, offices, and cultural venues. Transit-oriented development anchored by ART, and the return of true university-town vitality along Central Avenue. The bones are already there. We just need to zone—and believe—for it.

Currently, the area is zoned for mixed use but only along Central. Just one block away, on Silver Avenue, a proposed coffee shop was recently appealed for being “out of context,” an old, racist term still used in planning. Aside from that, though, let’s be honest: the “context” is one block from an ART station and a major institution. The context doesn’t prohibit mixed use, it demands it. That’s the kind of procedural mismatch that keeps Albuquerque stuck. Rezoning the entire UNM sector to allow more organic, place-based development isn’t just smart policy: it’s essential. We can’t keep holding ourselves back, especially adjacent to our largest employer and one of the state’s most powerful centers of gravity. If Philadelphia or Los Angeles feel too distant, look no further than Tempe’s university area developments. We can have the same at UNM. After all, the center of the universe is located just next to UNM’s duck pond.

But this vision doesn’t stop at the core.

Envision a reimagined Cottonwood area, primed for “sprawl repair,” no longer just a sea of surface parking, but a dense, walkable hub. A mix of housing types from apartments above retail to townhomes along shaded side streets. ART buses now connect the area seamlessly to the core, while new shops and services cater not just to mall-goers, but to a new generation of westside residents who want a true neighborhood—not just a shopping destination. At a natural crossroads of the western half of the metro area, and already home to a transit hub, the area could help give westsiders more job opportunities (and fewer headaches in cross-rio traffic). This plan would allow Albuquerque to create a true center, bringing in tax revenue, sustainability, and new life to an area that is beginning to show very visible signs of decay.

At Journal Center, the Rail Runner becomes the spine of new housing, light industry, and office growth, turning the area into a modern transit village. Already a job center, the area currently lacks good transit connections, including to its Rail Runner Station. Leveraging its central positioning between both I-25 and the railway, Journal Center could become a true center, with housing, cycling, and serve as a revitalized hub for Northeast Albuquerque. Connections to Downtown and Santa Fe help anchor it.

In Volcano Heights, we retained its designation as an Urban Center as it is currently defined in the Integrated Development Ordinance (IDO). Envisioned as an urban center planned with respect to the Petroglyph National Monument and with input from neighboring tribal nations, it was originally seen as a future way to bring jobs to the westside in a sustainable and respectful manner. However, the area remains largely undeveloped today. Recently, the city approved proposals to expand Paseo del Norte through the corridor. Anchoring the area with new transit lines, townhome developments along narrow, sustainable streets, and strong active transit connections will build on the momentum of the Cottonwood area’s sprawl repair and help prevent further sprawl to the west of the volcanoes.

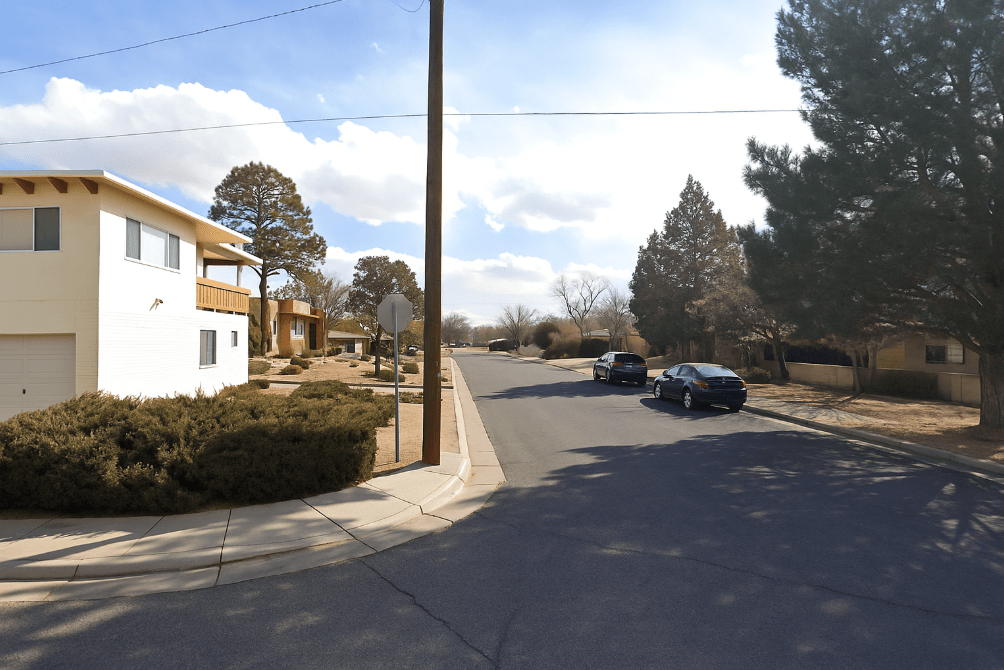

And across the Northeast Heights and suburban areas of the westside, quarter-acre lots evolve, allowing for homes in scale from single-family homes to duplexes and fourplexes. Quietly and organically, this allows these areas to evolve to its needs and desires, just as we described above in Las Cruces.

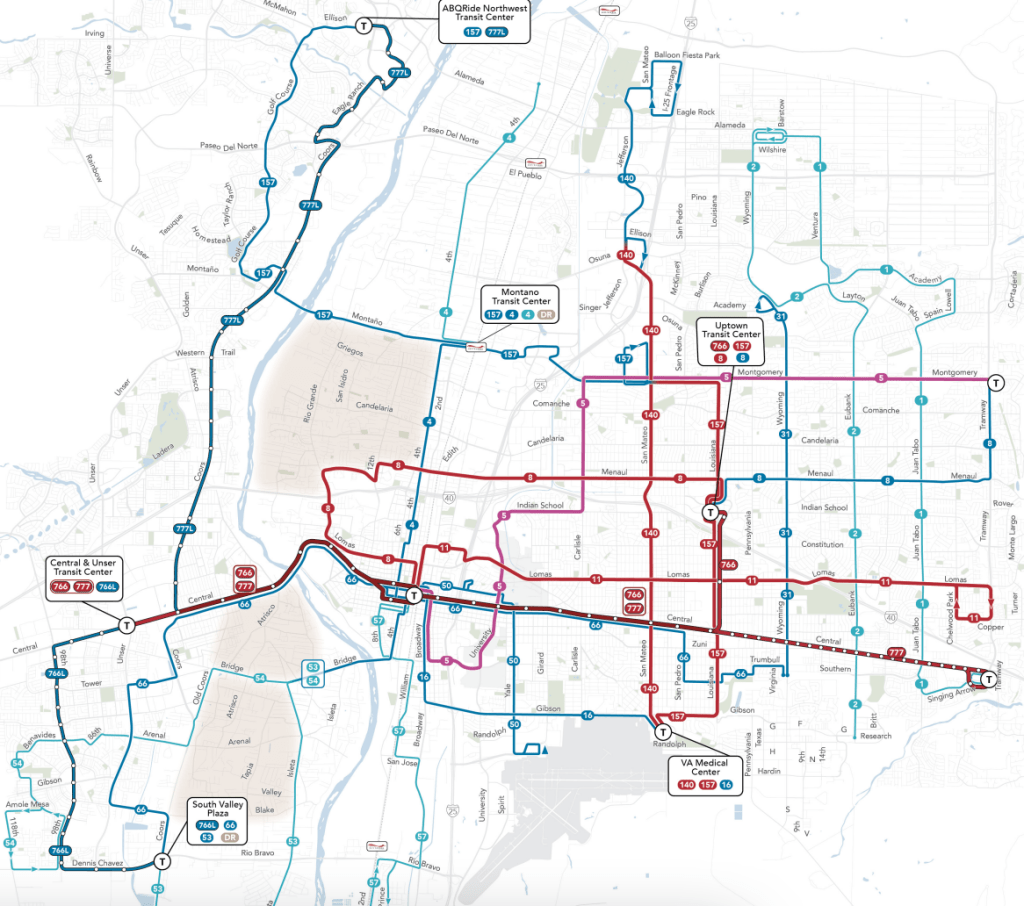

This is how we begin. By defining our Urban Character Areas, starting with a strong and coherent Central Albuquerque zone. But also identifying key sites across the metro that are already primed for new energy, better land use, and more equitable growth. Then, we allow our suburban areas to evolve, too. Families can split a home into a duplex, renting out part of it as a studio apartment for extra income, and retaining the value of their home (and ability to keep it in a good state of repair). Entrepreneurs can turn a backyard shed into a small workshop for their business, or provide childcare for neighbors commuting into Central Albuquerque on enhanced ART lines, which would now serve areas like the Southwest Mesa thanks to the ABQRide Forward Initiative.

This is what “Realize Albuquerque” can be. Not a utopian dream, but a realistic, replicable strategy rooted in what already works—and what our city urgently needs.

From Zoning to Justice

Legalizing apartments in neighborhoods shouldn’t be controversial. It already exists here. Walk the streets around Jefferson and Marquette, or Monroe, Quincy, and Adams. You’ll find a natural mix of housing types—single-family, casitas, fourplexes, and small apartments—coexisting beautifully. These areas were built in the post-war era, long after Huning Highland but before zoning became a tool to sterilize our city’s housing patterns. Yet time and again, when reforms are proposed, opponents claim that places like Nob Hill, Huning Highland, or West Downtown are somehow unique—that the “context” is different, and that post-war areas can’t support the same flexibility. But neighborhoods in the Highland District prove otherwise. The mix already exists. The “context” argument isn’t just flawed—it’s often a stand-in for preserving exclusion. It denies renters and entrepreneurs access to opportunity, and it weaponizes nostalgia to protect scarcity.

Equally vital is legalizing neighborhood retail—a long-overdue correction to zoning’s exclusionary history. As Yoni Appelbaum explains in Stuck, exclusionary zoning wasn’t just a policy failure—it was a tool of segregation. These land use rules first emerged to target small businesses run by Chinese immigrants in Modesto, California, before spreading nationally as a way to uphold racial and economic separation. Once the Supreme Court began striking down explicit racial covenants, zoning stepped in to do the same work more quietly. Ending the ban on corner stores, small grocers, and cafés is more than a zoning reform. It’s a matter of economic justice, of social resilience. These are third places where community grows and everyone gets a chance to stake their place within the larger community.

Bloomberg reports in “The Corner Store Comeback” (October 2, 2024) that “planners around the country are learning more and more the background of zoning—its extreme limitations, extreme exclusion and how zoning doesn’t really deliver the communities we want to live in. Communities happen organically; communities happen because of flexibility.” Urbanist groups like Strong Towns have been documenting this shift for years, noting how zoning reform can reignite neighborhood-scale commerce and human-scaled development. Their 2024 piece, “Loosen Up: How Mixed-Use Zoning Laws Make Communities Strong”, lays out the case plainly: when we stop outlawing neighborhood businesses, neighborhoods get stronger.

“One of the things you have to have in combination with middle housing is the ability to have business incubation space,” said Pasadena Planning Director Laura Dock. “People want to be in neighborhoods and be entrepreneurs at the same time, and having to expend a lot of capital because space isn’t nearby prevents a lot of people from entering the market.” Las Cruces understood the assignment—and got it done.

And yet in Albuquerque, appeals continue to be filed against basic projects like a coffee shop on Silver Avenue, next to a bus rapid transit station. As Las Cruces Councilor Johana Bencomo put it, “You should ask yourself where that segregationist tendency comes from.”

A “Realize Albuquerque” initiative would let our neighborhoods breathe. It would allow evolution—casitas here, a fourplex there, a new café at the corner. And most importantly, it would shift power from rigid rules and performative obstruction to a people-first model of planning.

Las Cruces has shown what’s possible. Albuquerque shouldn’t settle for less. Our city doesn’t have to start from scratch. Las Cruces just handed in the right answers. All we need to do is stop pretending the test isn’t in front of us.

Let’s stop defending decline, let’s envision a better future for Albuquerque. Let’s realize our future.

Leave a comment