The debate over reclassifying Menaul Blvd reveals who gets to shape the city’s future and whose fears are still driving land use policy.

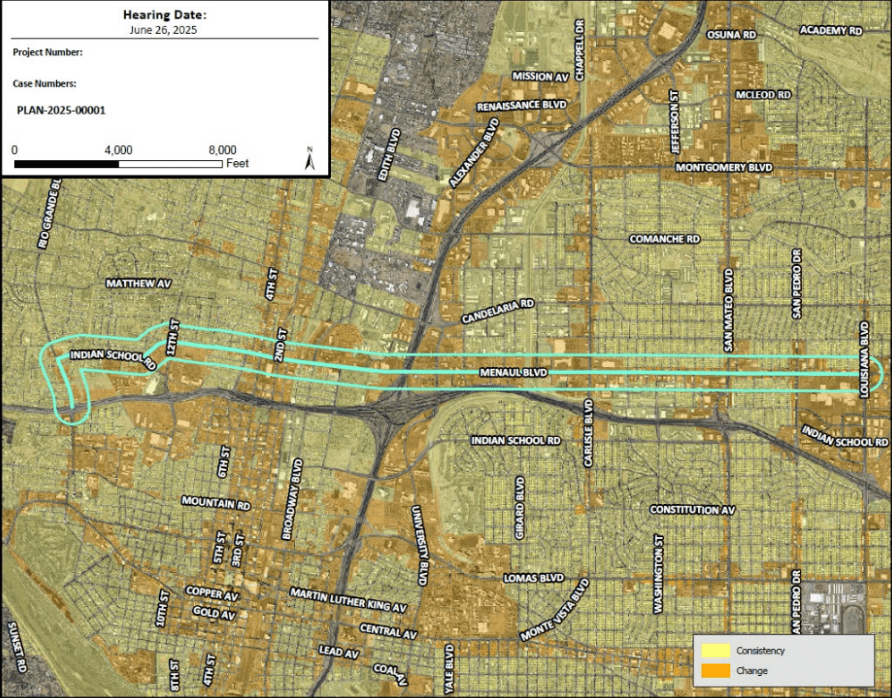

Albuquerque’s Environmental Planning Commission (EPC) is considering a deceptively modest change to the city’s Comprehensive Plan: reclassifying Menaul Boulevard from a “Multi-Modal Corridor” to a “Major Transit Corridor.” On paper, it’s just a map update. But in practice, it’s a statement about where and how this city should grow—and who gets to shape that future.

A Long-Awaited Shift Toward Coherence

Menaul has been a transit workhorse for decades, but its land use designation has lagged behind. After the lines serving Central Avenue and San Mateo, Route 8—serving the Menaul corridor—is one of the busiest in the city. The ABQ Ride Forward Network, adopted in 2024, identified it as one of the city’s most important east-west transit routes. Service on Route 8 is set to increase from 40-minute headways to buses every 15 minutes during the day—one of the biggest reliability upgrades in the system.

The redesignation does not force zoning changes, but it lays essential groundwork. It aligns the city’s long-range land use framework with transit investments already underway. It unlocks tools for mixed-use development, walkability improvements, and context-sensitive density in areas already slated (or desperately in need of) for growth.

The Public Response: Enthusiastic, Informed, and Overwhelmingly Positive

Residents from across Albuquerque weighed in, and the message was clear: they support the change. Dozens of comments from transit riders, renters, young professionals, and neighborhood association members called the redesignation a critical step toward affordability, climate resilience, and more equitable development.

“Menaul is becoming more than a road. It’s a corridor for people.” — Public comment

“Far from undermining neighborhood character, modest infill and walkable design reveal that our communities are even more vibrant and resilient than we’ve allowed them to be.” — Letter of support

Groups like Strong Towns ABQ and Generation Elevate New Mexico called the update long overdue, pointing out how it supports broader goals of reducing car dependence, expanding access to housing, and fostering investment in underutilized urban corridors1.

This is what planning looks like when it works: a thoughtful re-alignment of public policy with public investment, supported by a growing coalition of residents ready to move past 20th-century sprawl.

Opposition Echoes Familiar—and Concerning—Rhetoric

Yet not everyone is on board. Some traditional neighborhood associations and coalitions, particularly in the North Valley and Martineztown, submitted letters of opposition. Many call for a deferral, citing concerns about public process. But several go further, invoking language that raises red flags.

“This plan creates a pipeline from historically underserved areas into higher-income neighborhoods… exacerbating social friction by artificially forcing connectivity between neighborhoods with very different needs.” — Opposition comment, June 2025

This language may sound innocuous, but it carries a troubling echo. Similar arguments were used to block MARTA’s expansion into suburban Atlanta in the 1970s, explicitly to prevent “undesirable” riders from crossing neighborhood lines2. In cities across America, opposition to transit investment has often masked deeper fears: of change, of integration, of housing that isn’t just for the already-comfortable.

Albuquerque should not repeat those mistakes. Equity doesn’t mean freezing neighborhoods in place—it means opening up access, opportunity, and mobility to everyone, especially those historically left out.

“Areas of Consistency” Shouldn’t Mean Areas of Inertia

Several opponents argue that Menaul’s western segments lie within so-called “Areas of Consistency,” planning jargon for zones meant to preserve existing character. But character isn’t policy. And these designations, like Character Protection Overlays (CPOs), have too often been weaponized to block even the most incremental change.

Despite the alarm in some public comments, these protections remain in place. The redesignation doesn’t override zoning or force upzoning. The fears being raised are preempted by the very rules critics claim are under threat.

What this conversation does highlight, however, is a deeper current running through Albuquerque’s planning history, one shaped by protectionism, exclusion, xenophobia, and a fear of change. We’ve seen it before: when neighbors stalled The George, a modest infill development near an ART station, despite its alignment with citywide goals. Other appeals have delayed or defeated housing near high-frequency transit, preserving dysfunction in the name of “neighborhood character.”

Planning based on protectionism, rather than potential, leads to stagnation—not stability.

A National Movement Albuquerque Should Join

Cities across the country are recognizing that land use and transit planning must evolve together. From Portland to Minneapolis, Los Angeles to Austin, corridors like Menaul are being reimagined as hubs of walkable, mixed-use, transit-connected life—not just wide lanes of traffic and parking lots.

Albuquerque doesn’t need to reinvent the wheel. But we do need to get serious about aligning our policies with our values and goals. This redesignation is part of that work. It’s not a silver bullet but it is a crucial step toward a more coherent, equitable city.

The redesignation isn’t just about buses. It’s about unlocking the full potential of a corridor that stretches from some of Albuquerque’s most culturally and economically significant nodes: from Downtown and Old Town, past the Indian Pueblo Cultural Center and Plaza Avanyu, through the Menaul Metropolitan Redevelopment Area (MRA), all the way to Uptown.

This stretch of Menaul has long felt like a paradox: geographically central, but economically and physically fragmented. The MRA was created to change that. Already, Councilor Fiebelkorn has proposed allowing property owners in the area to selectively upzone for mixed uses, enabling housing, studios, workshops, small-scale industry, and street-level retail that can bring life and jobs back to this corridor3.

With Route 8 set to run every 15 minutes, this spine of Albuquerque could evolve into something more than a traffic conduit. Like Broadway in Denver—once a fading arterial, now a thriving arts district—Menaul could become a linear neighborhood: a place to live, work, create, and connect.

The Major Transit Corridor designation gives this vision a foundation. It supports transit. But it also supports housing, placemaking, economic revitalization, and cultural connection. It sets the table for Albuquerque to reclaim a neglected space at the heart of its map—and make it a place people choose to be.

Let’s Not Miss This Moment

The EPC has a clear choice: follow the voices demanding a future-oriented, transit-supportive city or let a few entrenched interests slow things down in the name of “process.” The reality is that the public has spoken and the Council recently approved Transit’s plan. The investment is underway. And the opportunity is real.

Let’s make Menaul a corridor for people—not just cars. Let’s pass the redesignation.

The EPC will hear and decide on this change on Thursday, June 26th, 2025.

- https://documents.cabq.gov/planning/environmental-planning-commission/2025/06-June/48%20Hour%20Materials/Agenda_2_PLAN-2025-00001_Comp%20Plan%20Amend_Menaul%20MTCorridor.pdf ↩︎

- https://kinder.rice.edu/urbanedge/new-study-examines-how-historic-racism-shaped-atlantas-transportation-network ↩︎

- https://www.krqe.com/news/politics-government/new-proposal-would-let-albuquerque-businesses-turn-property-into-housing/ ↩︎

Leave a comment