In the Name of the Modern

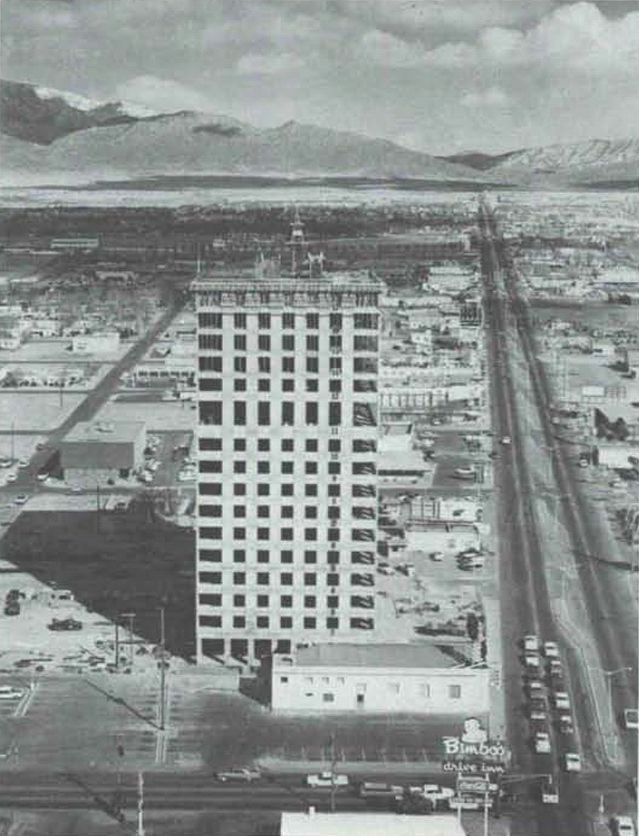

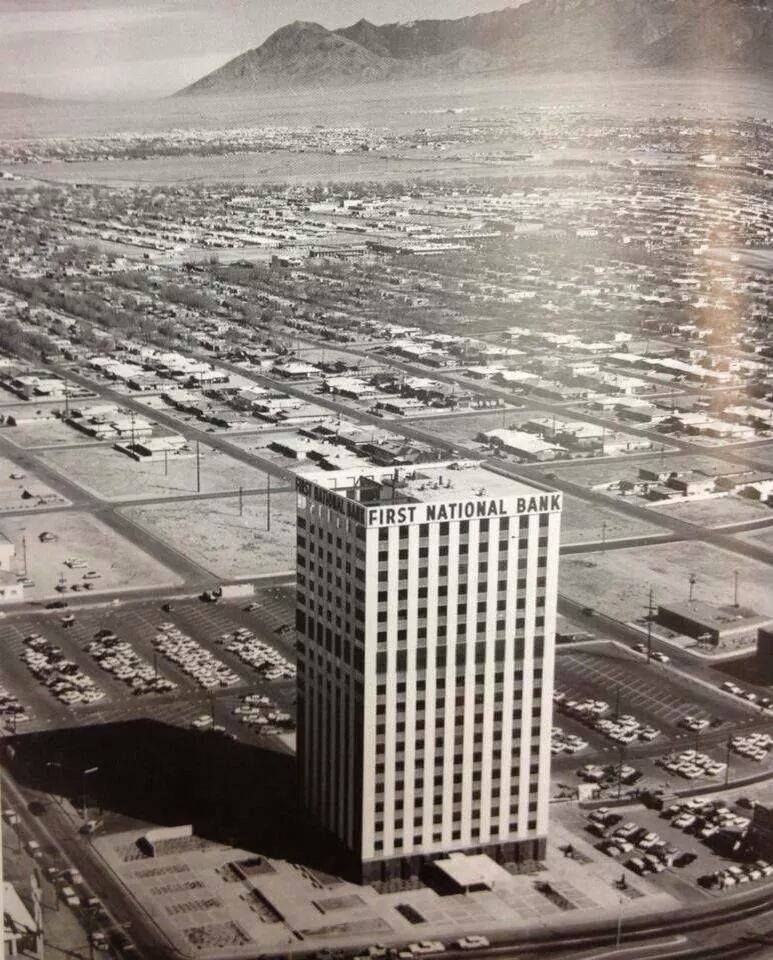

The tallest building in New Mexico opened its doors on a Saturday in February.

A crowd filed through the lobby of the new First National Bank Building East, admiring the glass and steel, the imported Italian marble, the modern lighting fixtures, the hospitality room that could seat a hundred. They signed guestbooks. They shook hands with assistant cashiers. They registered for a chance to win one of fifty $50 savings accounts. The bank had been chartered in the teeth of the Depression, but now, thirty years on, it had more than $100 million in deposits and a branch network that stretched as far as the city’s ambitions.

From the sidewalk, the new tower shimmered in gold leaf. Rising 213 feet into the sky at Central and San Mateo, it was declared “Albuquerque’s newest and most striking landmark,” likened, maybe with some irony, to the Eiffel Tower, the Statue of Liberty, the Taj Mahal. A monument, in glass and concrete, to growth1.

But what was striking wasn’t just the height. It was the location.

This wasn’t the city center. It wasn’t even close. The building stood miles from Downtown, far from the courthouse square and the old hotels Franciscan and Alvarado, and the brick storefronts along Gold. This was East Central, a stretch of Route 66 where the city bled into tract housing, drive-ins, car lots, motels. And yet it was here, not Downtown, that the bank planted its flag.

Here was where the people were going.

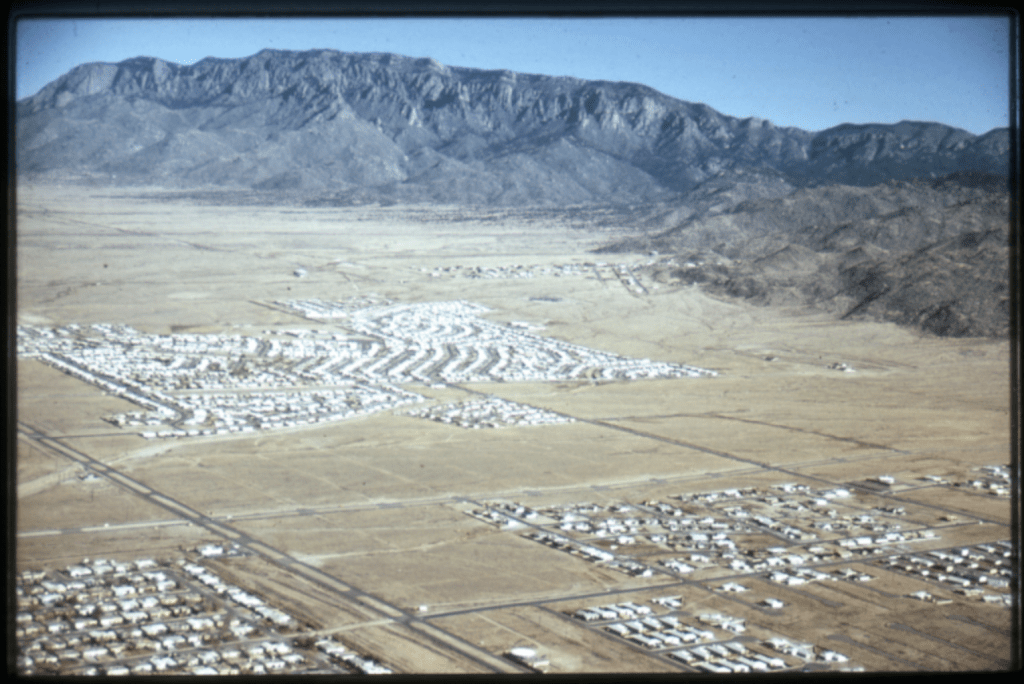

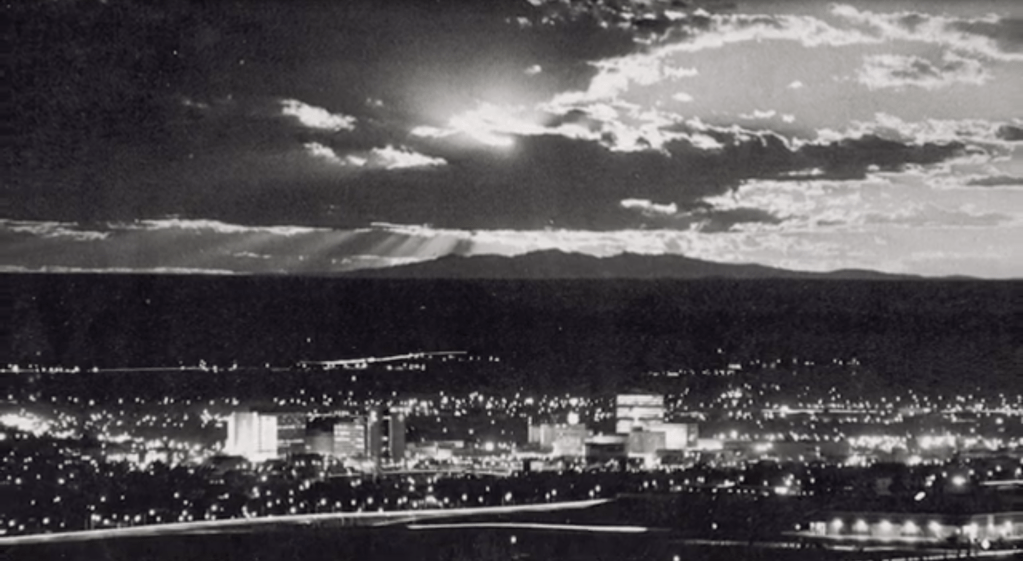

By 1963, Albuquerque was not just expanding—it was rearranging itself. The center was no longer central. Downtown had grown sleepy, dusty, left behind. The future—modern, mobile, master-planned—was happening somewhere else.

The bank’s East tower didn’t just represent this shift. It performed it. A skyscraper on the suburban fringe. A real estate department built to handle the business of growth. A new kind of landmark for a new kind of city: decentralized, horizontal, ever outward.

This was the beginning of an era. Of freedom behind the wheel. Of three-bedroom ranch homes with picture windows and carports. Of the “amenities” promised by zoning maps and FHA loans. Of a land use pattern designed not to enrich the center but to bypass it.

The age of the modern had arrived—not as a theory, but as a building, and a parking lot, and a thousand cul-de-sacs to follow.

Zoning Becomes a Footnote, Urban Renewal Arrives

In the same year the bank tower opened its doors on East Central, the city began to acknowledge what it had long resisted: the 1959 zoning code was already obsolete.

The consultants said as much—Harland Bartholomew & Associates, a St. Louis firm with forty years of experience and the prestige of having shaped cities from coast to coast, came on to help the city chart a new course. Their analysis, published in 1962, called the old ordinance “extremely sketchy.” It could not be salvaged. It needed to be replaced. The entire city, they wrote, had changed too quickly and too dramatically to retrofit old regulations2.

By 1965, the new ordinance was ready.

But zoning was no longer front-page news. When the final reading was announced, it appeared quietly on page A5 of the Journal, tucked between refuse bids and streetlight approvals3. The reform that once took years of wrangling and wide-eyed debate had become a footnote, a given, a tool of the modern city rather than a question.

Opposition didn’t come from civic organizations or civil rights groups. It came from the Home Builders Association, concerned mostly about parking requirements and a provision that shifted public hearings to a new “buffer” officer who would summarize citizen testimony in writing. They voiced their complaints, extracted some amendments, and moved on4.

Zoning, once controversial, had become administrative. Despite being tucked away on page A5 and passing with little protest, the new ordinance carried consequence. One provision, long sought by Albuquerque’s planning staff but historically resisted by Downtown businesses and residents, finally passed: mandatory parking requirements. It marked more than a regulatory update. It was a symbolic pivot—a quiet but decisive step away from the dense, walkable core and toward a future shaped by wide lots, private driveways, and surface parking.

The requirement did not arrive in headlines, but its effects would echo for decades. Like other Western cities, Albuquerque was following the gravitational pull of the automobile—and the promise of personal freedom its advertisers and lobbyists so expertly sold.

Urban renewal, by contrast to zoning, had just begun to assert itself.

On the same day the zoning ordinance passed its third and final reading, the front-page headline celebrated something else: the unanimous approval of Albuquerque’s first federally assisted urban renewal project5.

The $2 million plan for South Broadway was called a “face lift,” a term as surgical as it was euphemistic. Over 500 buildings would be cleared. Nearly 600 families would be displaced6. The neighborhood—long the center of Black life in Albuquerque—would be flanked on one side by a new freeway and on the other by this so-called model redevelopment.

The language was clinical. “Improved circulation.” “Terminal facilities.” “General obsolescence.”

But what was being removed weren’t just buildings. They were homes, stores, corner lots, churches. Lives arranged around alleys and porches and small shared yards.

City officials, backed by the John Marshall Community Association, claimed 80 to 95 percent of the area’s residents supported the plan. But the reader, seasoned by decades of selective neighborhood input and long accustomed to the performative consensus of civic commissions, must ask: whose voices were recorded? Who was even in the room?

The push for South Broadway signaled a pivot. Zoning would recede into technical administration. Urban renewal would rise in its place, armed with federal dollars and a new vision of what the city should be.

Gone was Clyde Tingley—the old patron of Albuquerque urbanism, skeptical of freeways, wary of federal oversight, a political force unto himself. With him gone, so too was the last barrier to wholesale federal intervention.

Albuquerque had arrived late to urban renewal. Dallas and Phoenix were years ahead. But what the city lacked in timing, it would make up for in ambition. The goal wasn’t just improvement—it was erasure and replacement.

This was the beginning of a new chapter in land use: one that didn’t ask where people wanted to live, but decided where they should.

Thoroughfares & Arterials — The Stroad As Policy

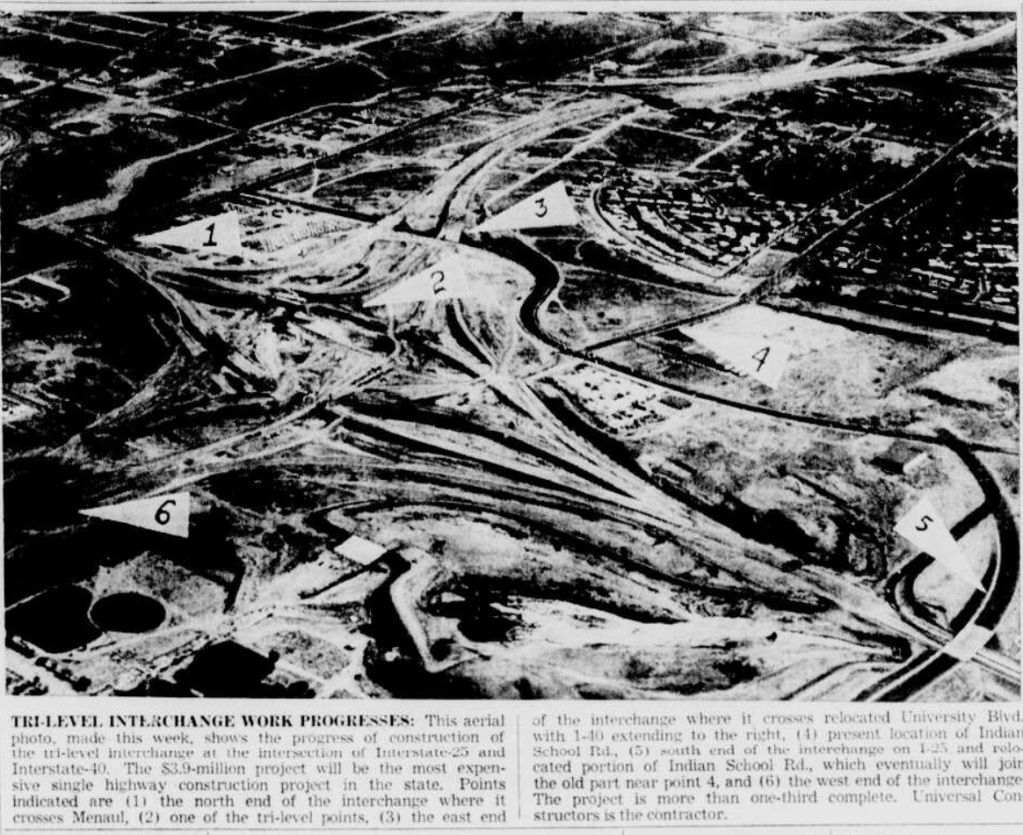

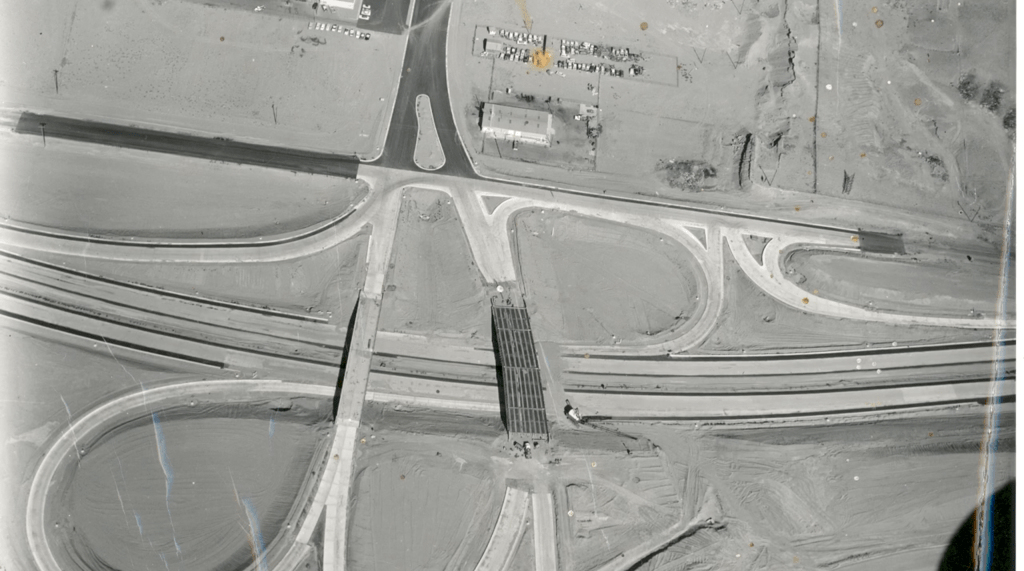

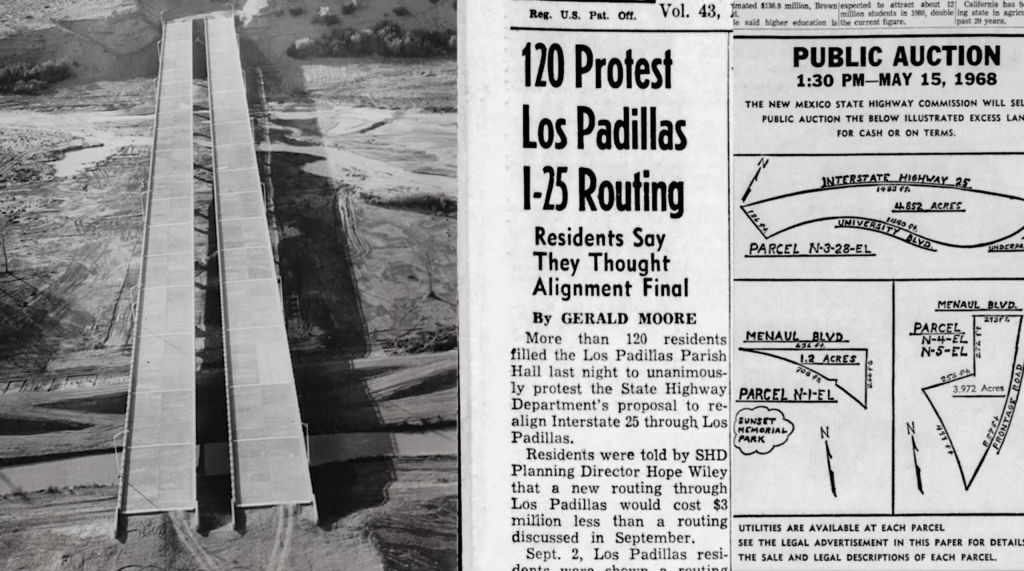

That same day in 1965, as the zoning ordinance passed almost anonymously on page A5, the front page also carried another sign of the times: an aerial rendering of a three-level freeway interchange, a knot of concrete designed to carry Albuquerque into its future.

The interchange would become known, in time, as the Big I. It was to be the most expensive public works project in the city’s history up to that time, linking highspeed superhighways that would replace the old Routes 66 and 85.

Here was the city’s new vision in literal overpass form—zoning tucked away in the back pages, while roads ascended front and center, crisscrossing over entire neighborhoods.

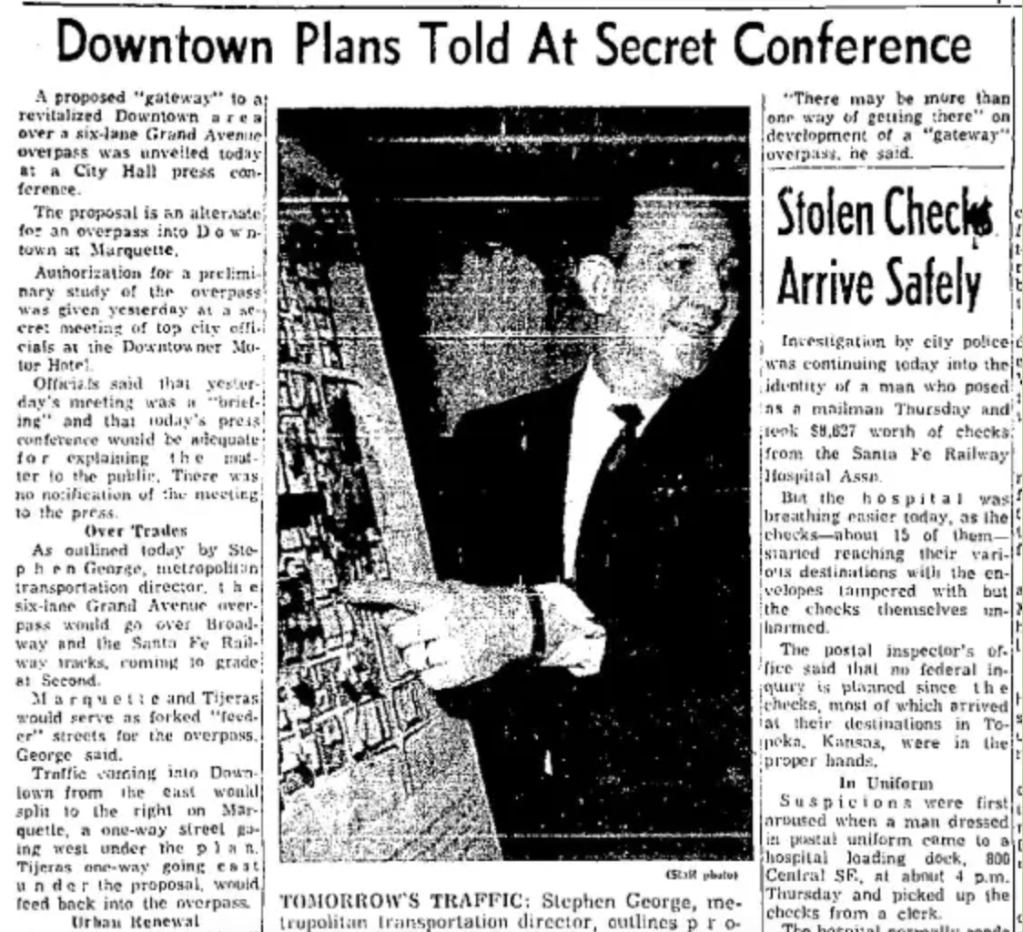

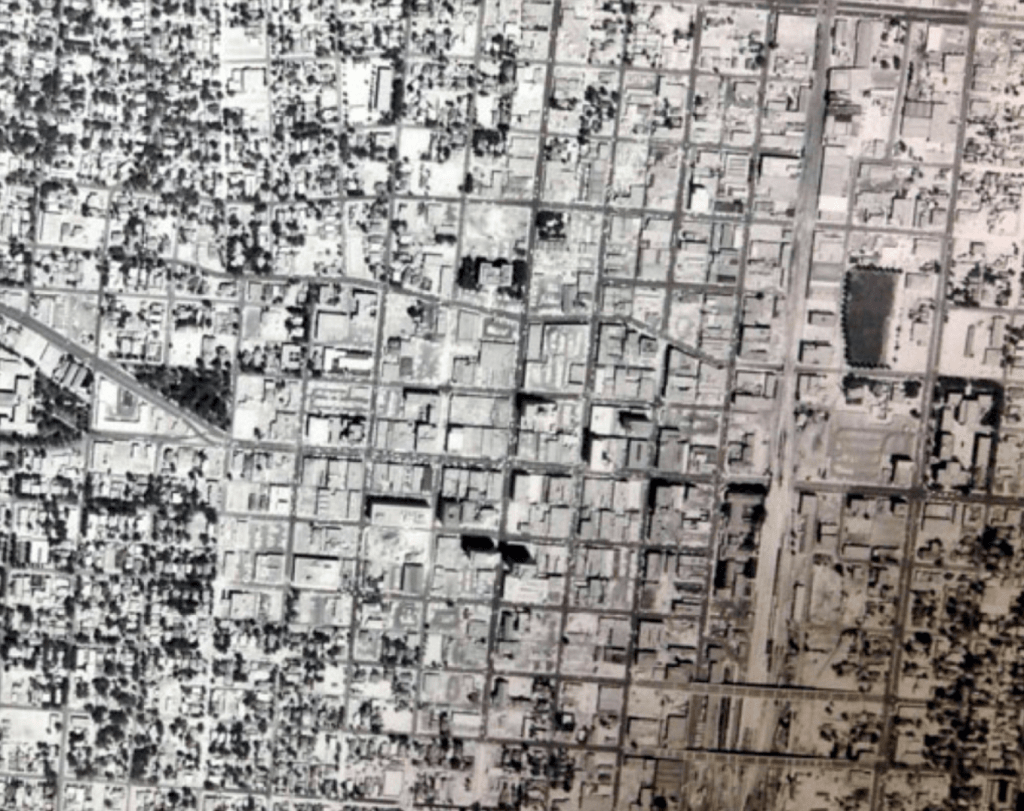

Downtown, by then, had become a problem in need of solution. City planning reports described it as stagnant, underutilized, and incomplete. There were too few roads, they said, and far too little parking. Side streets were narrow, awkward, and misaligned. Retail struggled and offices looked elsewhere. The people who remained—mostly older, poorer, browner—were not the ones officials imagined would carry the city forward7.

So the planners dreamed up something new: a Downtown designed for commerce, density, vitality—and cars.

They saw the central area as a blank canvas, a zone of potential despite the fact that in many ways, Downtown was still a vibrant neighborhood. Their studies spoke of mixed-use towers, new apartments, civic centers, sunken garages, arterial access, and high-speed approaches. One 1965 report promised that Downtown would “ultimately be served by terminal facilities, freeways, and interstate bus lines.” The lack of surface parking and quick access, it warned, was “a major deterrent” to the district’s appeal.

Albuquerque was late to urban renewal—but not late enough.

Not late enough to learn the lesson other cities would come to grasp too late themselves: that a city cannot raze its soul and expect prosperity to take its place.

Trying to plan for everything—jobs, residents, shoppers, commuters, traffic engineers—they ended up planning for no one.

And so they began to level it. Block by block.

Some wounds were surgical, or presented as such, like the redevelopment of South Broadway. Others were blunt-force.

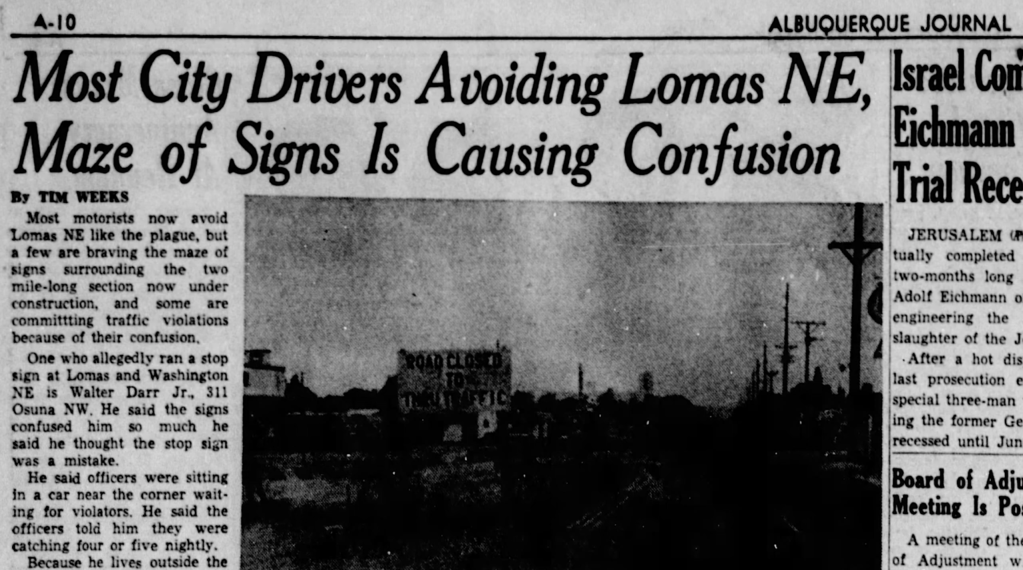

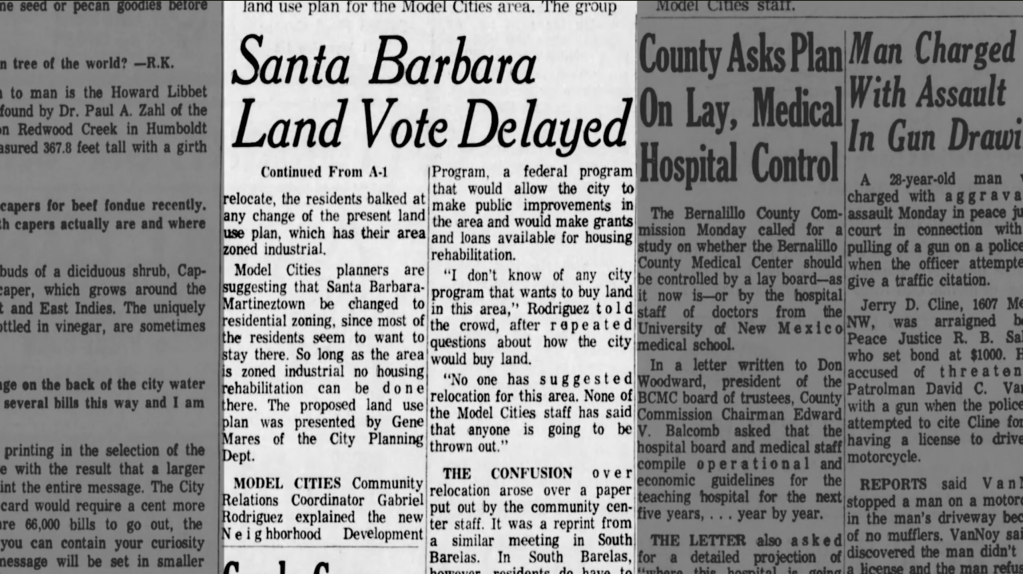

Lead and Coal were widened, cutting fast one-way trenches through residential neighborhoods. University Boulevard was straightened and expanded. In the process, it plowed through early 20th-century sanitariums, some with garden courtyards and river-stone walls, repurposed as apartments or clinics or small hotels. By the 1960s, they were declared “blight” and “shanty towns.” Neighbors and officials alike demanded their swift removal8. Lomas was rerouted and expanded to serve the new superhighway, adding links to Downtown for the suburban commuters that would one day stream down the boulevard into the gleaming office towers. Like the sanitariums on University Avenue, large portions of Santa Barbara-Martinez Town were also labelled blight to help along this march toward progress.

City Manager Sam Engel praised the changes. This, he said, was how a modern city should work: fast-moving arterials feeding into a dynamic Downtown, connected to an expanding grid of high-capacity expressways9.

And for a moment, it looked like momentum. The maps filled in. The highways advanced. And the new Downtown, they assured the public, was just over the horizon.

But it never quite arrived.

Instead, what came was emptiness. Emptiness wouldn’t be seen in the plans. The plans themselves were exciting.

The Battle for the Center: A City Looking Elsewhere

A Blank Canvas (With Better Parking)

In the mid sixties, there was a moment, quiet but telling, when Albuquerque came close to turning its back on Downtown for good.

The question wasn’t rhetorical, It was literal. Where, exactly, should the city put itself? Where should its government meet, where should its deals be struck, its conventions held, its decisions staged?

By then, Downtown was a question mark. The hotels were closing. The old train depot was struggling amidst rapidly declining ridership. Civic life, to the extent it existed, had begun migrating east. Shopping followed the subdivisions. The streets that once held the city’s weight were now holding parking lots and vacancy signs.

So it was not absurd, at least not then, to imagine a new city center far from the one it already had.

A March 1968 Albuquerque Journal article reported that a site near Winrock Shopping Center was being seriously considered for the city’s new Convention Center10. Another editorial proposed placing the civic center in “an area adjacent to Coronado Center,” citing ease of access, fresh image, and parking abundance as selling points.

The land around these rising malls shimmered with possibility: wide boulevards, no traffic jams, no history to get in the way. Developers promised a blank canvas and a clean break—civic identity, if you like, in the form of a mall-adjacent parking lot.

The Journal covered these ideas with the civic optimism only midcentury could muster. Civic leaders toured sites, engineers sketched mockups and the city’s future seemed, briefly, like it might take place in Uptown or at the base of a new freeway interchange.

And yet, Downtown lingered.

There were editorials. Counterproposals. A stubborn belief—articulated more in nostalgia than in vision—that a city needed a center. Eventually, Downtown won the bid. Civic Plaza was sited near the remnants of Fourth Street. The Convention Center rose on the bones of demolished boarding houses, beloved department stores, and forgotten bars.

But the fact that it was ever a question—whether to abandon the core entirely—tells you everything about the city at that moment. Not just what it was willing to do. But how close it came to doing it.

Downtown Albuquerque: Ambition by Demolition

As the freeway interchanges took shape and arterial roads carved deep into the city’s fabric, Albuquerque faced a crossroads, not just of traffic, but of civic identity.

What, exactly, should Downtown become? With the Big I rising to the north and retail and residents migrating east and then west, planners and city leaders began to reimagine the core—not as a relic to preserve, but as a canvas to reshape. They looked to other cities undergoing urban renewal: San Francisco, Phoenix, Dallas, Denver. Mixed-use towers. Civic centers. Structured parking. A new Downtown designed not for what it was, but for what it might become by 1980.

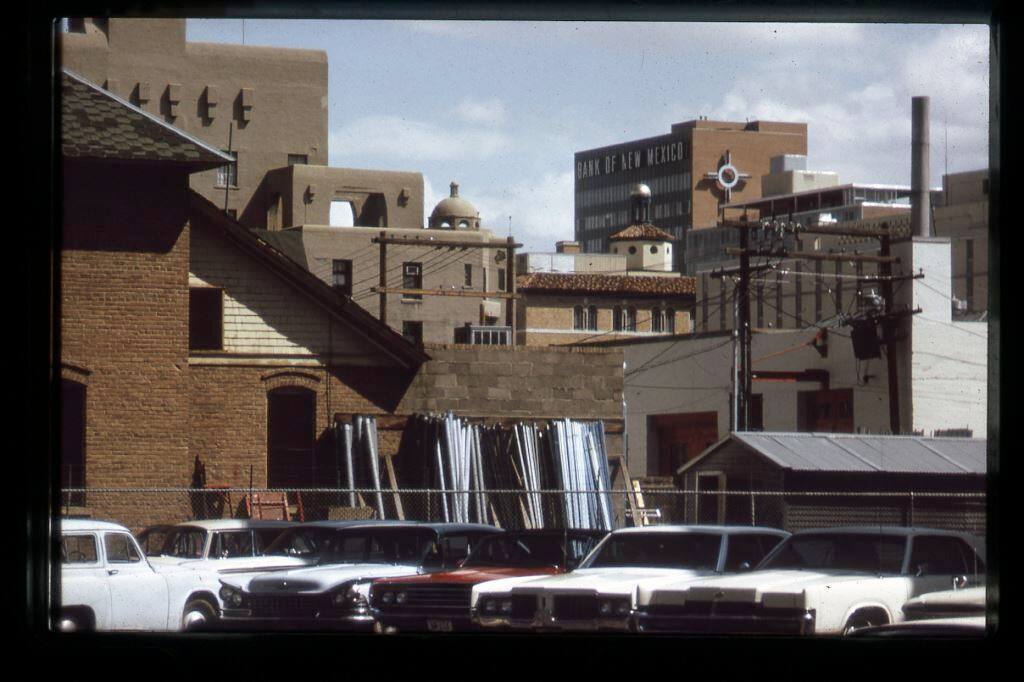

Reports framed the existing grid as obsolete, worrying old roads were unwelcoming to motorists. Investment had stalled, shoppers had fled, and old buildings were seen as liabilities more than landmarks. In response, the city launched a wave of planning studies and redevelopment proposals aimed at “revitalization”—a term that, in practice, meant erasure and replacement.

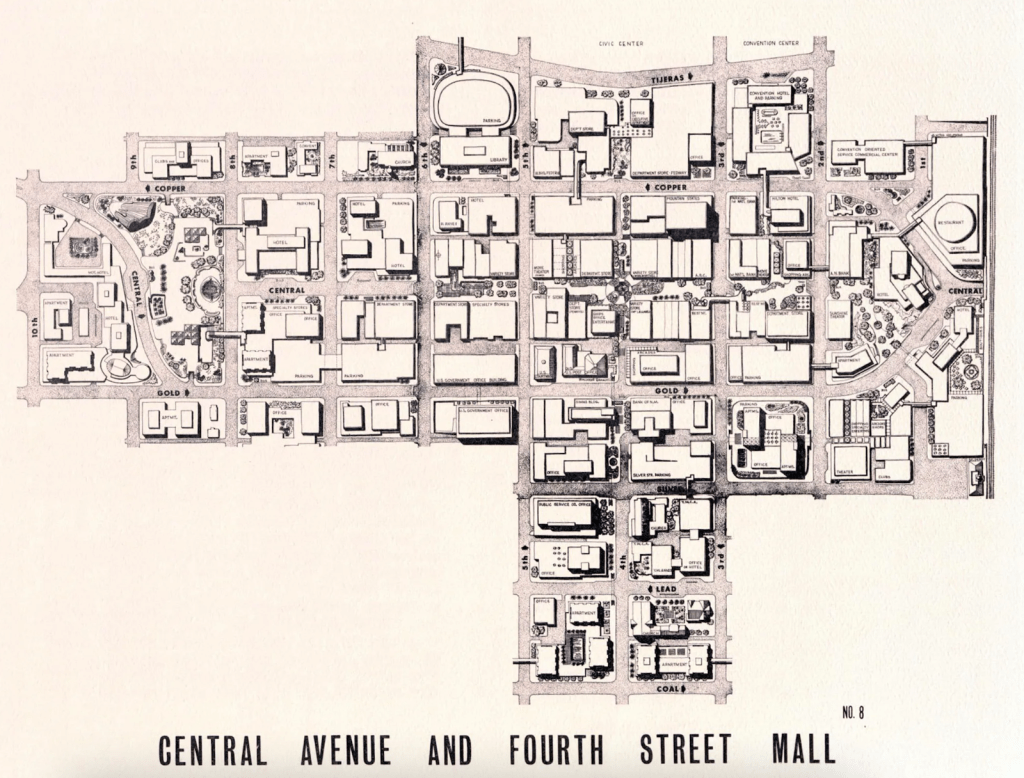

Civic Plaza was envisioned as the anchor. The Convention Center would follow. Offices, government buildings, and pedestrian malls would complete the plan. It was bold, forward-looking, modern—and in many ways, deeply flawed.

But Downtown, against the odds, held on.

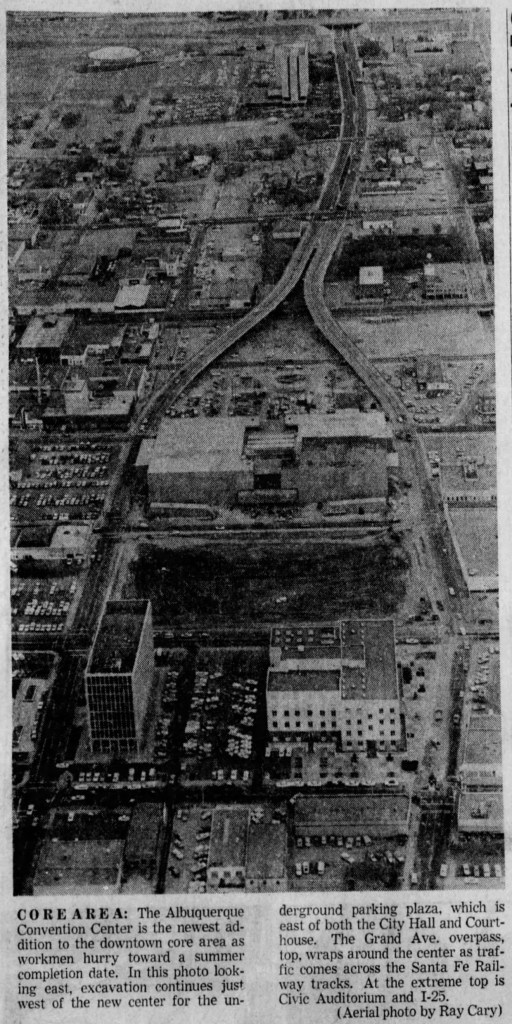

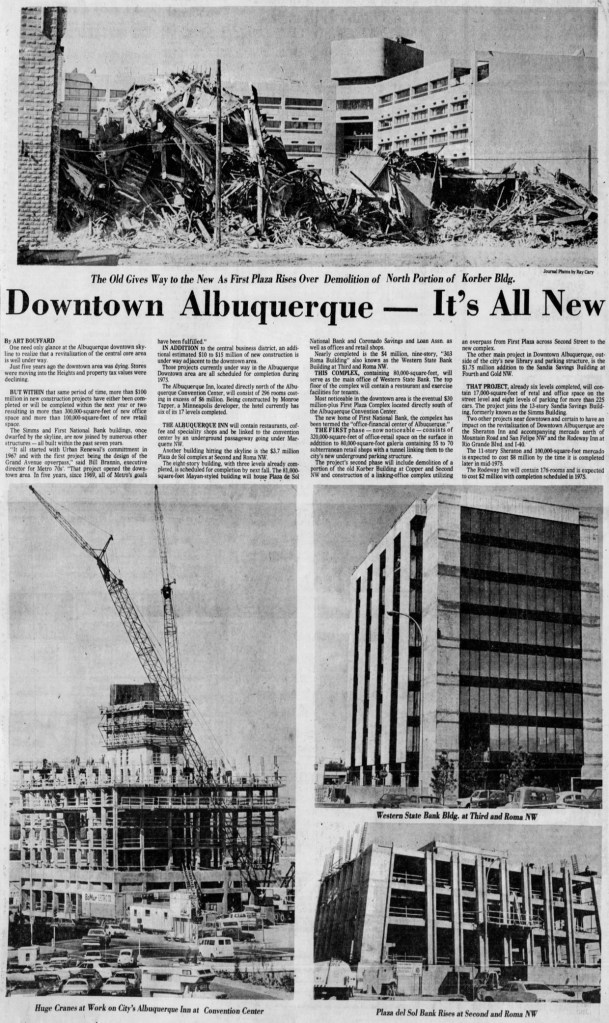

After years of delay, civic leaders chose to anchor Albuquerque’s future in its core. The Convention Center was ultimately sited west of the railroad tracks, just north of the old City Hall and east of the Courthouse. The First Plaza Galleria and the Plaza del Sol rose in its wake. New banks went up on Roma and Third. In newspaper clippings from 1972, bulldozers flatten blocks of the Korber Building, promising that “Downtown Albuquerque—It’s All New.” Cranes towered over the construction of the Convention Center, casting long shadows on cleared lots and demolition dust.

Yet what the city imagined as renewal now reads as removal.

In these photos, we see the physical traces of erasure: block after block flattened, cleared for structured parking or left fallow. The “core area”, as one caption put it, was now defined by overpasses and underground garages. Where homes, hotels, and neighborhood shops once stood, the city created plazas and arterials. Gold Avenue and Copper Avenue were widened into one-way, multi-lane stretches; Fourth Street was turned into a pedestrian mall and blocked off at Central—ironically eliminating the spine that once animated the city.

It was, in many ways, a textbook case of modernist planning. Various Downtown Plans, starting largely in 196511, envisioned a district of clean lines, glass towers, sunken walkways, and efficient circulation. A “Hall of Justice” with a parking podium was imagined on what is now Martinez Town. It also called for a civic plaza that would “bring the people back” and imagined Central Avenue as a pedestrian spine—a space for festivals, strolling, and public life. Fourth Street would be pedestrianized too. Surrounding this new heart would be structured parking, widened boulevards, and high-speed access from every angle.

It sounded bold. Progressive. Even utopian.

And to be fair, much of it was onto something. The plan recognized, correctly, that car-oriented expansion had hollowed the center. It saw that people needed a place to gather, not just shop. But it misunderstood what makes those places work. When you build pedestrian spaces to function like indoor malls—sanitized, segmented, anchored by government buildings and parking garages—you haven’t recreated the energy of a city. You’ve built a facsimile. A stage set. A civic gesture more than a civic habitat.

In trying to preserve urban life, the planners froze it. They imagined Downtown as a showcase rather than a workshop—something to be admired from afar, rather than inhabited. And in doing so, they built a space that could not compete on its own terms. Albuquerque wasn’t alone in this. Las Cruces did the same with its Downtown pedestrian mall, and cities across the country followed suit. The result, almost everywhere, was the same: empty walkways, vacant storefronts, office towers that drained at five. A model built for people that somehow forgot to invite them in.

The result was a cityscape that emptied out. “People-centered” in theory, it proved sterile in practice. The Civic Plaza, a concrete expanse flanked by bureaucratic towers, remains underused even today, despite years of programming, art installations, and revitalization efforts. It is a space without shelter or shade, designed for symbols rather than citizens. A stage for the idea of public life, not public life itself.

This was the paradox of Downtown renewal: it sought to rebuild Albuquerque’s center, but did so by removing the very ingredients that once made it work—density, small parcels, fine-grained commerce, streetlife, and social friction. In one photo, the entire civic core appears surgically excised from the city grid, surrounded by parking and highway-like roads. A new downtown, yes—but for whom? And at what cost?

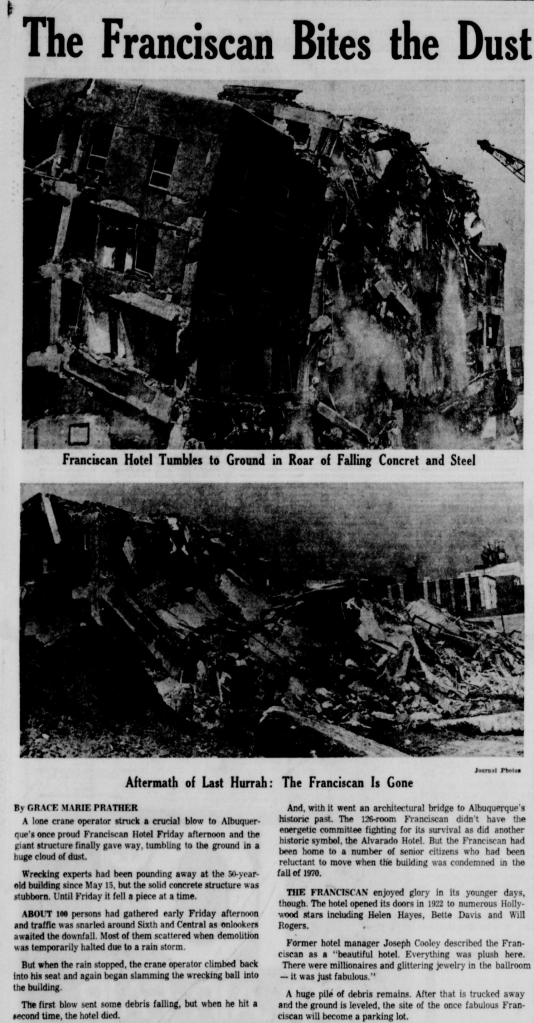

It was a moment not noted in plans or policy briefs, but it said as much about the future as any rendering could. One structure rose while another fell. One built for the new image of Albuquerque: sleek, glassy, unencumbered. The other, fallen from favor, was cast aside with all the solemnity of trash day. The city had made its choice.

This, too, was the modern. Not just in the towers or the arterials, but in the ease with which something could be unmade. A historic hotel, a street grid, a neighborhood, a community of workers, artisans, bankers, bellboys, and bureaucrats—none were sacred if they stood in the way of momentum.

Much of this vision was formalized in the Tijeras Urban Renewal Plan, adopted in the early 1970s. It treated the downtown grid as a canvas for surgical reinvention. The plan mapped out the removal of so-called “blighted” blocks around Tijeras, Gold, and Copper, clearing space for government buildings, pedestrian malls, structured parking, and new arterial realignments. Like so many plans of its kind, it promised revitalization through removal—public plazas where homes once stood, office towers in place of shops, high-speed roads to deliver the people who would never stay. It was urban renewal not as repair, but as rupture.

At its edges, the plan stretched even further. Whole swaths of Martinez Town, one of the city’s oldest and most culturally rich neighborhoods, were labeled “blight” to make way for new civic facilities—a high school, an auditorium, widened thoroughfares. In the end, Albuquerque’s tardiness to the urban renewal playbook spared Martinez Town the full weight of destruction. The school and auditorium were built east of the neighborhood instead, tucked along the sandhills that would soon be carved out for Interstate 25. But the damage, though partial, was real12. Grand Avenue (now Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard) was widened, claiming homes and history. Broadway was straightened. Mountain Road was cut into pieces. The projects may have been scaled back, but the scars remain.

It is tempting to say Albuquerque got off easy compared to cities like Detroit or Los Angeles. But trauma doesn’t measure itself in relative terms. To be declared “blight” is not a wound that heals easily. Suspicion of local planning still lingers, passed down through generations. Even today, the ghost of the Tijeras Plan lives on—not just in the vacant lots and widened arterials, but in the deep mistrust of official language, of promises dressed in community benefit.

What the city failed to bulldoze, it slowly extracted. Investment drifted east to the mesa, then north to the Heights, then west beyond the river. And while some of Downtown’s most extreme interventions were never realized—Central Avenue was never fully closed, for instance—others were. Copper and Gold were converted into one-way couplets for high-speed traffic, only recently restored to something more human-scaled. Fifth and Sixth. Second and Third. Each one carved up the grid in the name of “circulation.”

What remains is neither historic preservation nor modern vision—just a patchwork of loss. Meager attempts have been made to repair it. But the empty lots persist. And with them, the memory of hotels, workshops, boarding houses, community halls, and the people who once gave Downtown its pulse.

Albuquerque did not destroy its downtown in the way of Los Angeles or Detroit. It spared many of the buildings, many of the blocks. But it hollowed them out. It gutted their context. It turned density into vacancy, and vibrancy into vacancy studies. It chased vitality with blueprints and models and, when that failed, with demolition crews.

What emerged was not a new city, but a rehearsal. A version of urban life flattened and widened to fit a parking minimum. A Downtown designed to impress from the air, not to be walked on foot.

And yet, the bones remain.

The city did not move to Winrock or Coors. It stayed. Bruised, cratered, disconnected—but present. Even now, the ghost of the Franciscan lingers in the sunlight on Central, just as the echo of jackhammers haunts the quiet mornings on Civic Plaza. Downtown is still here. But so is the memory of how easily it could have been erased.

On the same weekend that bank tellers shook hands and served coffee under imported marble on San Mateo Boulevard, a lone crane operator downtown struck a final blow. Concrete groaned, the roof gave way, and the Franciscan Hotel, once among the city’s proudest addresses, tumbled to the ground in a roar of dust and rebar. Fifty years of memory collapsed into a pile of debris. By dusk, the site was leveled. The hotel that once hosted Helen Hayes and Will Rogers would become, in time, a parking lot.

The Shape of Things to Come

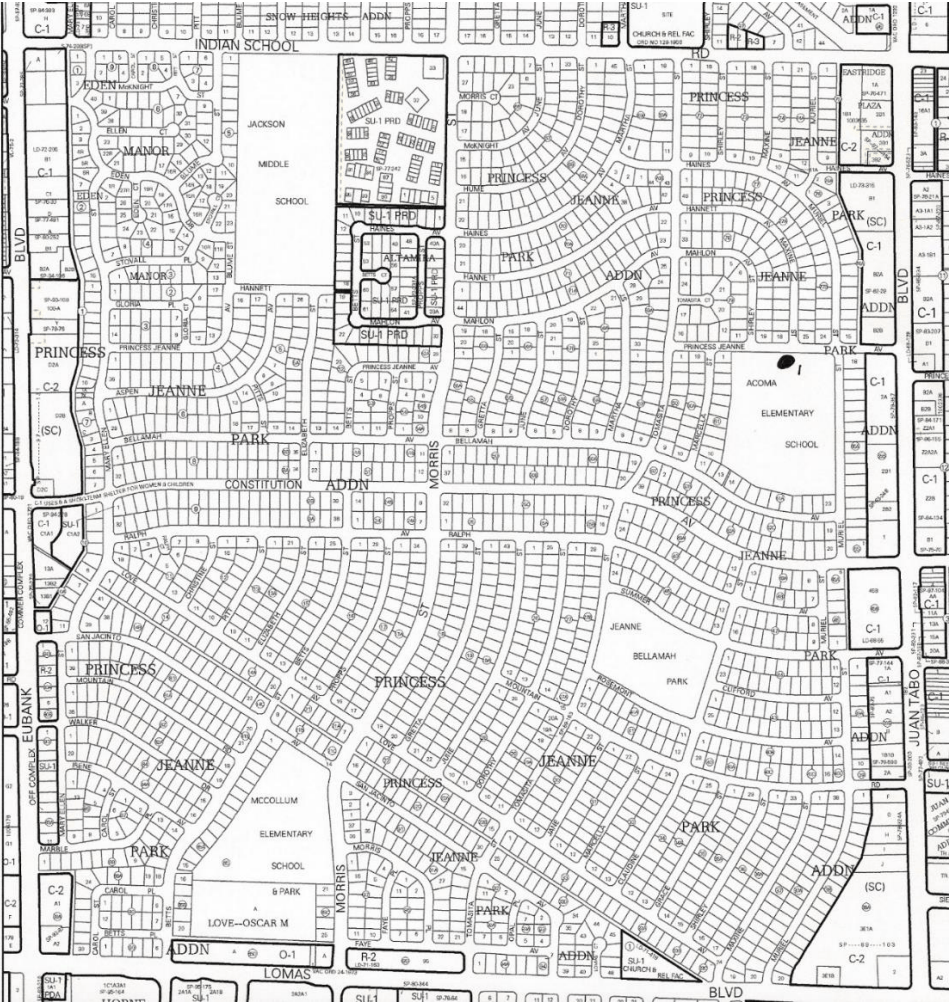

There are neighborhoods that emerge, and neighborhoods that are declared. Princess Jeanne was the latter.

Built in the 1950s and early 60s by developer Dale Bellamah, Princess Jeanne was more than a subdivision. It was a brand and a model. A suburban experiment scaled to the size of a city’s eastern expanse and bringing it in line with the large tract developments now springing up from East Coast to West Coast. The ads called to the modernist appeal saying “Open the door on tomorrow.” Another said, “Everywhere you look the view is new when you have a new subdivision, new streets, and all-new models of all-new homes.” These phrases promised not just shelter but an entire way of life—sprinklered lawns, rear-facing kitchens, two-car driveways, and a sense of order so absolute it bordered on choreography. As UNM’s Modernism Project notes, this marketing wasn’t just aspirational: it was exclusionary. It advanced a sanitized vision of postwar domesticity rooted in whiteness, conformity, and rigid gender roles: “images of cheerful housewives, orderly lawns, and nuclear families framed the neighborhood as a haven for respectable, middle-class (implicitly white) domestic life.13”

Each cul-de-sac had its own rhythm. Homes came in variations; ranch, pueblo revival, pitched gable; but the differences were cosmetic. What mattered was the pattern: setbacks, sidewalks, street widths calibrated for the car. A zoning map brought to life and a future delivered one poured slab at a time.

In Princess Jeanne, Albuquerque built not just houses but a thesis. Here was the argument for private life over public life, for quiet over friction, for amenity over encounter. The street became the unit of social order. The garage replaced the plaza. The front yard was not a place to gather—it was a signal: of tidiness, of propriety, of staying in your lane. Earlier suburban developments largely continued Albuquerque’s grid patterns toward the east with minor variations. Princess Jeanne disrupted the grid, played more into setbacks and uniformity and would in many ways become the blueprint for the city’s next era14.

This wasn’t sprawl as mistake; it was sprawl as aspiration.

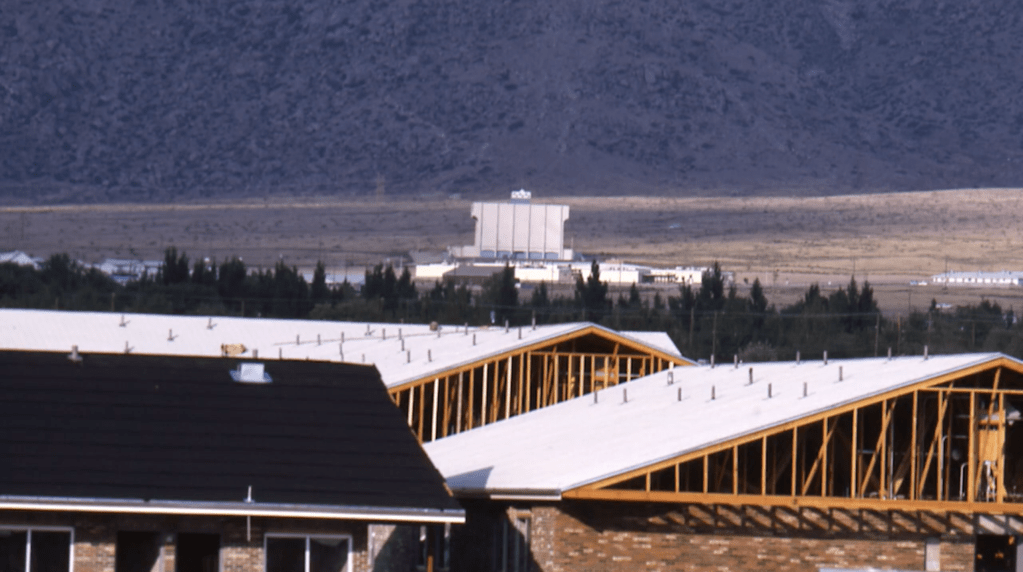

And it wasn’t just happening in the cul-de-sacs. A few miles west, on Louisiana and Indian School, a new kind of civic gravity was taking shape.

Winrock Center opened in 1961 as a marvel of the age15: an indoor, climate-controlled shopping mall that promised luxury, leisure, and escape. Developed by Winthrop Rockefeller and anchored by stores like Montgomery Ward and JCPenney, it was less a retail destination than a declaration that Albuquerque’s center of gravity was shifting.

Here, amid polished floors and piped-in music, a new kind of public life emerged: one made of indoor storefronts instead of sidewalks, atriums instead of plazas. It was modern, manicured, and unmistakably suburban. And it worked. Winrock and its neighbor, Coronado Mall, became magnets for investment, siphoning attention, energy, and capital away from the aging Downtown core and accelerating white flight.

Civic leaders noticed. By the mid-60s, there were serious proposals to site civic centers near these rising commercial centers. A city that once formed around a train depot and courthouse now imagined its future anchored to a shopping mall parking lot.

And yet It felt like optimism. The Cold War was ambient but distant and the military and labs continued to funnel families into the Southwest at a high pace. The West was still imagined as an open canvas and for many who moved into these homes; young families, GI Bill beneficiaries, engineers lured by the labs; it was the dream made real. A mortgage in reach, a room of one’s own, in a neighborhood named after the developer’s wife.

Princess Jeanne gave form to a broader shift. No longer was the city a place of density and interdependence. It could now be a collection of islands linked by arterials, buffered by private yards, zoned for predictability. If Downtown had once symbolized common space, Princess Jeanne represented its opposite: a city turned inward.

This physical template would be repeated, block for block, on the mesa and beyond the river. What began as a hopeful eastward push would later be cloned on the Westside at scale. If Princess Jeanne was the pilot program, the Westside became the proof of concept—cul-de-sac after cul-de-sac stretching toward the volcanoes, each one a faint echo of Bellamah’s original promise.

Albuquerque’s suburban experiment wasn’t an accident. It was engineered by developers, planners, and politicians who saw growth as both inevitability and gospel. In the 1960s and 70s, that gospel found its patron saint in city leader, then Senator, Pete Domenici, who helped steer federal funding to roads, labs, housing, and hospitals16. It was a pro-growth consensus so complete it became invisible. The shape of the city came to reflect the ideology of its stewards.

Many of those stewards left their names behind: Bellamah. Snow. Hoffman. These were not neighborhoods so much as signatures—autographs etched into asphalt and deed restrictions. Dale Bellamah perfected the model with Princess Jeanne. The Hoffmans helped shape the East Mesa’s early contours—first with Hoffmantown, then with scores of single-family subdivisions stretching east toward the Sandias. These men transformed former grazing lands and flood-prone arroyos into tract homes, shopping plazas, and cul-de-sacs. Their legacy is still visible today. Hoffmantown Shopping Center’s mid-century sign towers, a little weathered now, over the corner of Menaul and Wyoming—a monument to an era when suburban growth was the city’s organizing principle, and eastward was the only direction that mattered.

The Westside’s eventual rise, via Taylor Ranch and beyond, would carry the Bellamah aesthetic across the river. What was once an exception became the rule: driveways and carports over doorsteps, traffic volumes over walkability, a city built to be driven through. Trees planted in medians, not to shade children on sidewalks or walkers in the sun, but to wither, diseased and gas-choked, in the exhaust of passing traffic. The people were never meant to be near them anyway.

But at its root, the story began here: in Princess Jeanne. In the idea that a good city was one where neighbors could live side by side without ever needing to share anything more than a fence line. The lifestyles that had long dominated the Southwest, in Pueblos and Spanish Plazas, and in land grant homesteads, were quickly being left behind. At the same moment that Princess Jeanne promised private refuge, Uptown offered its public counterpart: modernity for sale.

Winrock Center was more than a mall. It was an axis. A retail cathedral where the city’s emerging wealth and attention began to gather. Between the carports of the East Mesa and the air-conditioned corridors of Louisiana Boulevard, the geography of aspiration shifted. The energy that once radiated from the courthouse square now pulsed from the escalators of JCPenney. The new Albuquerque wasn’t forming around a plaza—it was forming around a parking lot.

And in that belief, Albuquerque found its new pattern.

Westward Ho: Dreams, Dead Ends, and the View from the Mesa

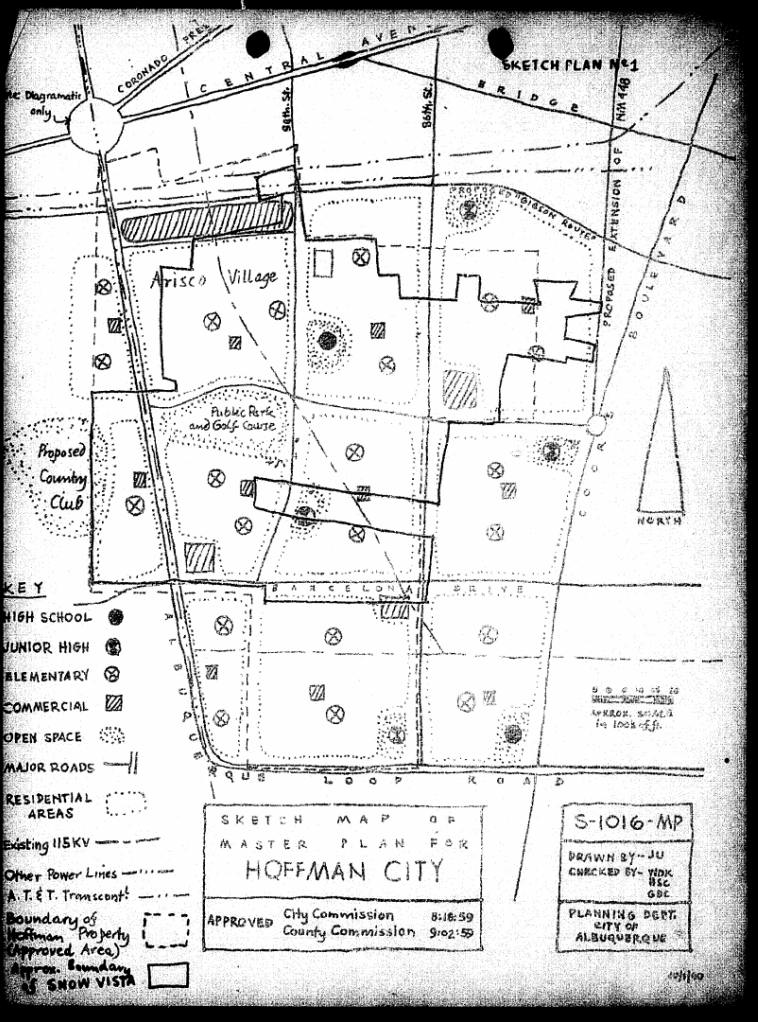

Hoffmantown was one of the East Mesa’s first proofs of concept, a master-planned center of commerce and subdivision, wrapped in midcentury optimism and financed by the engine of sprawl. Its signage still towers above Menaul and Wyoming, a weathered monument to a dream that mostly came true. But its twin across the river, Hoffman City, would never see the same fate.

That story begins at the end of the fifties, just as steel rose at San Mateo and Central for the new National Bank Building, and Winrock Mall began to take shape on the East Mesa. Sam Hoffman—the developer behind Hoffmantown—was looking west.

In 1959, he purchased a vast tract of land on the Southwest Mesa, part of the historic Atrisco Land Grant. His goal was audacious: to build a master-planned city bearing his name. Hoffman City. A place of subdivisions and schools, plazas and arterial roads. A new Albuquerque, but with fewer interruptions.

The East Side had been easy. Its land was cheap, its titles clean. Princess Jeanne, Hoffmantown, Snow Heights—each followed the same formula. Poured slabs, setbacks, promises. But the mesa was filling in and prices were climbing. As such, Hoffman’s gaze drifted across the river, to land developers had long avoided—agricultural, hard to reach, and complicated by centuries of communal ownership17.

The Westside was part memory, part margin. It was still mostly farm and ranch land and still held in trust by descendants of the Atrisco Land Grant. But even there, pressure was building. Trustees were open to proposals that would leverage the land and create value for its residents. Offers were growing. The east had been easy but it wouldn’t remain so for much longer and the west still held the promise of scale.

And so the deal was struck.

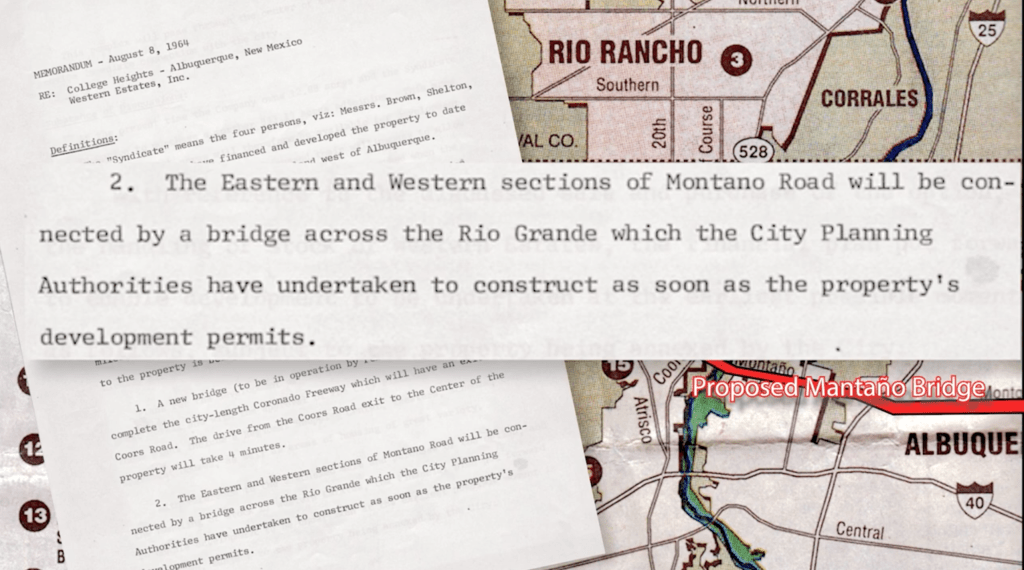

The Atrisco Land Grant, held in trust for the benefit of its descendants, had long resisted large-scale sale. But Hoffman persuaded trustees with a vision of transformation: thousands of homes, shopping centers, schools, and sweeping arterials that would stitch the mesa into the urban fabric. His plans even envisioned new bridge connections on an expanded Gibson Boulevard as well as through the Tijeras Arroyo on a new Albuquerque loop road tying together the city’s edges. “The subdivision, to be known as Hoffman City, is expected to contain shopping centers, schools, churches and be a city in itself” Hoffman stated to the Albuquerque Journal in 195918.

The trustees approved the deal, but their support alone wasn’t enough. Under the terms of the Atrisco Land Grant’s governance, any sale of land required a vote from the resident heirs. A public hearing was called. Debate was vigorous. Some spoke of opportunity, of how development would increase the value of the grant’s remaining holdings and bring long-overdue resources to the community. Others urged caution. The land, they said, held more than monetary worth. “The grant,” one opponent argued, “is culturally valuable,” a living inheritance to be preserved “for their children, just as their ancestors had done for them.”

In the end, the scale tipped toward growth. The vote passed by a wide margin—432 in favor, 115 against. It wasn’t without controversy. Only resident heirs were allowed to vote; 158 ballots cast by non-resident heirs were disqualified. But the outcome was clear: the land would be sold, and Hoffman City would move forward.

It marked Albuquerque’s first great leap across the Rio Grande.

But almost as soon as the ink dried, problems began to surface. Hoffman grew increasingly frustrated by delays. The Federal Housing Administration objected to his schematic plans, calling the layout of parks, schools, and roads “inconsistent with good planning.” Legal troubles followed. Some of the deeds Hoffman had acquired turned out to be forgeries—“about 10 per cent,” according to a later Journal report. The dream that had seemed so close at hand began to slip away. Infrastructure never materialized. Construction stalled. Lawsuits lingered.

The grand experiment was beginning to unravel not with a bang, but with a flurry of memos, rejections, and unmet deadlines.

Then came the tragedy. On the morning of October 13, 1959, Sam Hoffman was found dead alongside his wife, Jean Lucille, in their Phoenix apartment19. The scene was quiet. A maid had been unable to enter; the apartment manager opened the door. Inside, everything was in order—no struggle, no chaos, only a short note left behind: “The strain was too much.”

Hoffman had shot his wife in bed before turning the gun on himself. It was, as one headline put it, a murder-suicide that came “only weeks before the start of his latest housing project on the Albuquerque West Mesa.” He was 54. She was 46.

The news sent shockwaves through Phoenix and Albuquerque alike. Hoffman had not only been a builder of homes but a builder of cities—his name etched into streets, subdivisions, and shopping centers. He had arrived in Albuquerque nearly a decade earlier and helped reshape the East Mesa with developments like Hoffmantown and Inez. He was, in 1954, the second largest homebuilder in the nation.

Just days before his death, he had been preparing to return to Albuquerque to begin construction on Hoffman City. Friends said he’d sounded ready. The land deal had been finalized, 650 homes already sold, and the first 500 were scheduled to break ground as soon as FHA approval came through. But behind the progress, trouble had accumulated: challenges with the FHA, disputed deeds, delays in planning. His wife had been ill. Hoffman, friends said, had grown increasingly worried. It was all too much.

His death stunned colleagues. “It was a shock to all of us,” said a local supervisor. “But the project will go on.” The company, Hoffman Homes, Inc., was a family-run enterprise. His son, Jack Hoffman, and other relatives would continue the effort. The Atrisco board expressed confidence the plan would proceed. The city had annexed the land. The machinery of growth, once set in motion, would not stop.

But something had shifted. The man whose name had launched a city across the river was gone. In his place, others would work piece by piece to bring the reality of Albuquerque’s westside development to life.

The project would be passed into new hands. Ed Snow—another major developer, better known for his work east of the river and his namesake neighborhoods like Snow Heights—acquired the rights to what had once been Hoffman City. He rebranded it Snow Vista, hoping to salvage the dream and recast it in more pragmatic terms.

Annexation into Albuquerque, requested by Hoffman, was carried on by Snow. Though some descendants of the Atrisco Land Grant filed suit to stop it, the City Commission sided with the developer. “The City Commission today approved annexation of a 9,000-acre tract on the West Mesa, part of the Atrisco Grant, after being assured by city staff and legal counsel that the action was valid and in good faith,” reported the Albuquerque Journal on July 14, 196020.

But the problems that had haunted Hoffman didn’t vanish. The land remained remote and difficult to service—far from utility hookups, infrastructure still years away, and made only more complicated by its legal and geographic inheritance. The grand, contiguous subdivision envisioned in the 1950s had to be remapped, sliced into parcels, redrawn to fit the contours of what was economically feasible. Snow, despite his experience and connections, faced the same slow bleed of delays, red tape, and mounting costs. Snow Vista, like Hoffman City before it, never materialized as promised. By the late 1960s, the housing market had slowed, and Snow, like many developers stretched between ambition and infrastructure, found himself under pressure. Mounting debts and lawsuits from creditors followed. In 1968, at just 45, Ed Snow died of a heart attack. Officially, it was natural causes, a cardiac arrest. The stress of transforming the mesa into subdivisions had taken its toll21.

Yet some traces remain. The road grid, in places, echoes the original schematics—vestigial angles and cul-de-sacs sketched by Hoffman, then redrafted by Snow. On 98th Street, a ribbon of asphalt winds across the mesa. It was supposed to be part of the neighborhood’s arterial spine. Today it has an accompanying bike path: the Snow Vista Trail. To cyclists and joggers, it’s a route. To the city, it’s a name without a neighborhood. A ghost of what could have been.

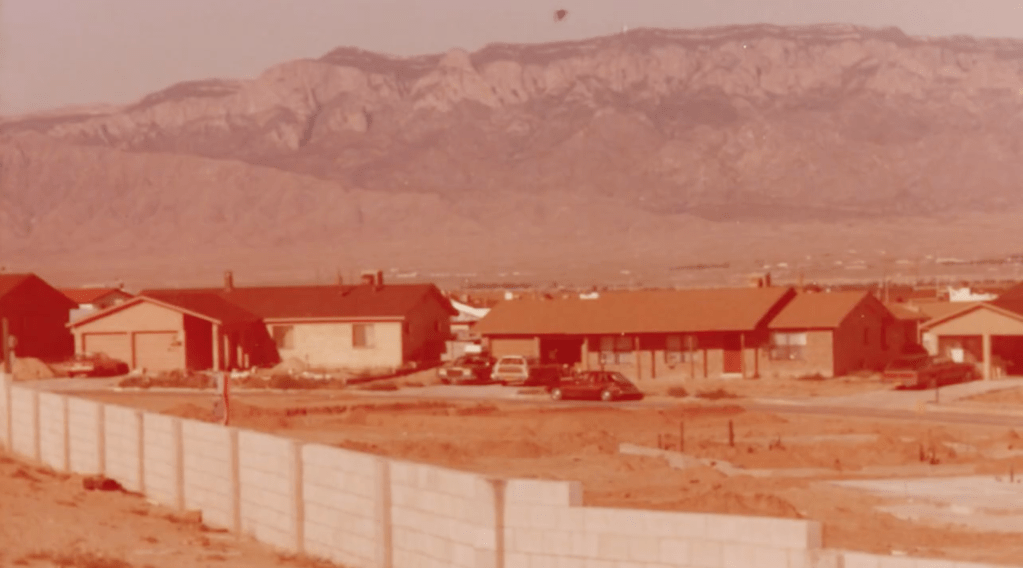

But the mesa would not stay empty for long. What began as Hoffman’s vision and Snow’s salvage attempt eventually yielded to market momentum and a rebounding housing market. In the absence of a singular, master-planned development, a patchwork of smaller builders stepped in. Ranch lands and homesteads were purchased and subdivided. Utilities were extended. Suburban templates were cut and pasted across the mesa. By the 1980s, the rim of the Westside was dotted with thousands of homes—driveways and garage doors facing the street, wide arterials guiding traffic out and in, schools and strip malls stitched in after the fact.

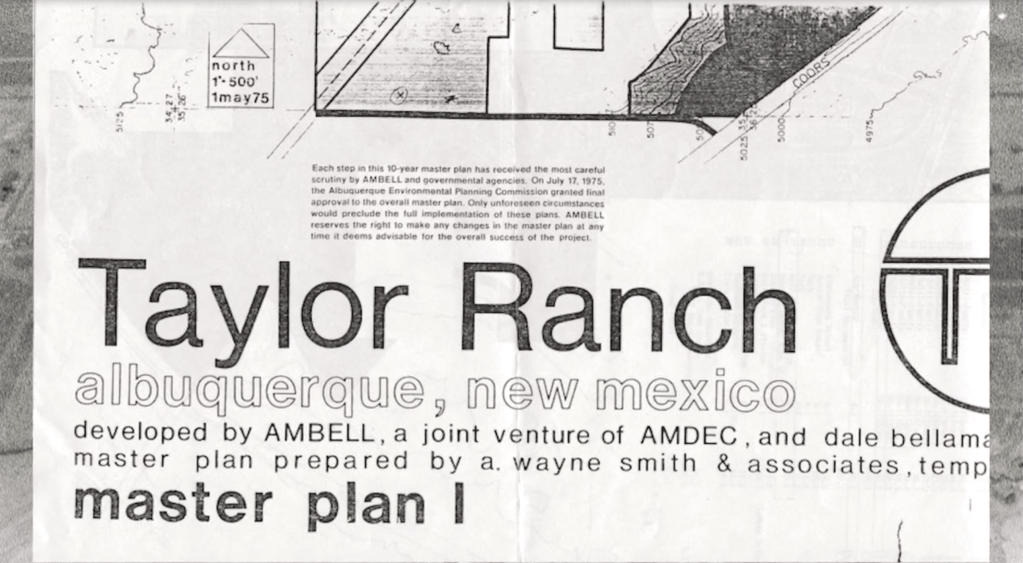

Taylor Ranch would become the standard-bearer on the Westside, and its aesthetic, a repeat of the Bellamah model, defined what came next. The cultural memory of the Atrisco Land Grant faded, buried beneath sidewalks and stucco. What had once been a bold leap across the river became routine. Not a city, but a stretch of subdivisions. Not a plaza, but a parking lot. The kind of growth that didn’t need a name.

The Westside’s eventual rise, via Taylor Ranch, Paradise Hills, and beyond, was less a break from the past than its reproduction at scale. Where the East Mesa had experimented with subdivision and sprawl, the West Mesa committed fully. Neighborhoods spread like ink on paper—wide-lot homes with low-slung silhouettes, fronted not by porches but by garage doors. Arterials carved deep lines across the mesa, organizing life around traffic flow rather than community form.

Joan Didion once wrote, “We tell ourselves stories in order to live.” Albuquerque, in its westward march, told itself it was protecting the land even as it consumed it.

Long before developers ever sketched out lot lines and cul-de-sacs, much of the mesa was open land grazed by cattle. As one of the Westside’s best-known subdivisions, Taylor Ranch, took its name from a family that had arrived from Chama in the 1930s. Each winter, they drove their cattle south across the state to graze the mesa’s high desert grasses. Eventually, they settled the land, building a working ranch and raising children on what was still the city’s fringe in simple adobe homesteads22. The mesa had a different rhythm then—seasonal, deliberate, quiet.

But by the 1970s, that rhythm was broken. As Albuquerque’s housing market surged westward, the Taylors sold. What had been pasture became pavement. The ranch gave way to tract homes. The name remained, but the place was remade.

This tension wasn’t new. The Westside (and Rio Rancho) would join the rest of the city in the tradition of advertising based on climate, views, and the dramatic nature of the Southwest. For over a century, Albuquerque had sold itself through the language of health and horizon. Early 20th-century brochures promised tuberculosis patients a healing climate and “pure” air. Sanitariums dotted the desert. Writers like Jack Kerouac, DH Lawrence, and Edward Abbey extolled the space, the silence, the light. Georgia O’Keeffe rendered the landscape sacred. Nature wasn’t just an amenity: it was the brand.

Developers seized on this legacy. The escarpment, the Rio Grande, the bosque, the Sandias; each postcard-worthy in the evening light became marketing copy. “Vistas of value,” one ad promised. “The best of Albuquerque from your own backyard.” But what they sold was impossible at scale: a city cannot stay rural forever. You cannot preserve the land by subdividing it.

Here was the paradox of the Westside: communities drawn to nature yet built in ways that degraded it. Homes offered views of what they threatened: the volcanoes, escarpment, bosque, mountains. People moved west seeking space, only to oppose anything that might allow others to follow. Roads were extended. Services strained. Schools crowded. And yet proposals for density, for transit, for mixed use were met with resistance if they were even considered at all.

Even before Taylor Ranch began to stretch across the West Mesa, the City Commission had given the contradiction a name: sprawlitis23. In 1964, as Westside development was still in its infancy, the Commission created the Albuquerque Metropolitan Development Committee to study the growing tension between outward spread and core investment. Chairman Westfall explained, “For the past year and a half or so a number of people in Albuquerque have become keenly and greatly concerned over our little condition of sprawlitis.” He clarified that while the Commission supported expansion, it could not come at the expense of the city’s core.

Residents, too, were growing uneasy. The climate and landscape that once drew people for healing, inspiration, and investment was no longer viewed simply as a resource—it was becoming a backdrop under threat. And yet, they kept moving outward. Like so many Western cities, Albuquerque wanted to grow without changing. It wanted open space without limits, vistas without neighbors, roads without congestion, and neighborhoods without density.

The Westside was sold as nature-adjacent, but its growth consumed the very landscape it admired. The escarpment was preserved, in theory, through setbacks and zoning overlays but the road to that protection was paved with rooftops. Bosque access was celebrated, but limited. Trailheads were praised, but parking lots proliferated. The more people came to love the land, the more they changed it.

By 1965, the city was already planning a new bridge across the Rio Grande at Montaño, a proposal that would spark decades of political debate and protest24. Even as development surged west, infrastructure raced to catch up. Schools were built, then clinics followed. Developers cut deals for new interchanges, new arterials, new tax breaks. The “view” that once inspired awe was now framed by powerlines and rooftops.

And still, the stories continued: that the Westside offered a better life, affordability not available east of the Rio, that the mesa was limitless, that Albuquerque could grow without consequence. But a new anxiety was settling in. When the city adopted its first Comprehensive Plan in 1975, it carved out vast swaths of land for open space preservation25, a quiet admission that something was at stake. Growth would continue, but now it came with a shadow: the growing fear of what might be lost.

But the city is now learning that stories have a cost. Infrastructure is stretched, commute times climb, and those who once fled Downtown now find themselves clamoring for the very things they left behind: walkability, proximity, connection.

What began with a failed dream—Snow Vista—has become a citywide reckoning. The view remains. But the vista, as an idea, has changed.

In the end, the Westside did not become Hoffman City. But it became something else: a mirror held up to midcentury hopes and late-century contradictions. It became Albuquerque.

Protecting What We Paved: The Birth of Environmental Rhetoric in Albuquerque Planning

By the late 1970s, a new vocabulary was entering the city’s planning discourse. Where earlier decades spoke in the language of growth and efficiency, planners and residents began to adopt words like character, ecology, and preservation. Nationally, Earth Day had come and gone. Environmental impact studies were becoming standard. And in Albuquerque, for the first time, formal “Open Space” was designated in planning documents—an explicit acknowledgement that growth had consequences.

But something else was happening, too. As Michael F. Logan writes in Fighting Sprawl and City Hall, environmental activism in Albuquerque was “a relative latecomer to the political arena.” It didn’t arise from deep ecological commitment alone. Instead, it evolved as a final iteration of anti-growth politics—one that replaced earlier rhetoric of efficiency, aesthetics, or assimilation with the language of conservation and environmental stewardship. What began as booster-driven promises of health and horizon evolved into something more defensive: sprawl wrapped in sagebrush, sold as stewardship.

And beneath it all, there lingered a dream: the dream of ruralism.

Albuquerque’s postwar growth was animated by a powerful promise: that one could live on the edge of nature, close to the city but far from its problems. Developers sold it relentlessly. Advertisements promised views, space, and silence. Suburbs were not just homes but sanctuaries.

But cities are not ranches and the more people came to claim the view, the more the view receded. Roads brought rooftops and service stations. Silence gave way to the constant hum of traffic. The natural beauty that had defined Albuquerque became something glimpsed in rearview mirrors, framed by fences, buried under cul-de-sacs.

Neighborhoods like Taylor Ranch and other emerging Westside communities (as well as those now encroaching onto the Foothills) were at the forefront of this rhetorical shift. Residents spoke of protecting the escarpment, preserving the viewshed, maintaining natural slope. But the solutions they proposed—wide setbacks, large lots, and strict single-use zoning—were not conservation measures. They were design templates for car-dependent sprawl. The landscape they sought to protect was being fragmented not by dense infill or vertical growth, but by the very subdivisions they championed.

This was the paradox: the rhetoric of preservation was used to entrench development patterns that consumed far more land, generated more pollution, and locked in unsustainable infrastructure. People who moved to the Westside for the views now resisted apartments that might block them. They praised the desert tranquility while building cul-de-sacs that stretched infrastructure thin. They insisted on protecting nature—so long as it didn’t involve living near it, sharing it, or changing how they lived.

The 1975 Comprehensive Plan attempted to confront these contradictions. It formally recognized the importance of directing growth and preserving key landscapes while it also carved out large areas for Open Space, especially near the West Mesa escarpment. But it did so while still approving sprawling development across the mesa, often on the assumption that enough setbacks or green buffers would somehow make sprawl sustainable.

In reality, it only made exclusion more permanent. Environmental concerns were not applied uniformly across the city; they were most vocal where homeowners were most organized. “Character” and “ecology” became politically effective shields for preventing change. New zoning overlays promised to “protect neighborhoods,” but what they often protected was a class- and race-based vision of the suburbs.

Albuquerque wasn’t alone in this shift. Across the country, what journalist Jerusalem Demsas later called the “Cautious Green26” emerged: activists and residents who spoke the language of sustainability but opposed its real implications—density, transit, integration. In practice, they reinforced the suburban status quo: low density, high segregation, and ecological sprawl.

By the end of the decade, Albuquerque had begun to internalize these contradictions. It wanted to preserve the land while paving it. It wanted to celebrate nature without letting others live near it. It wanted to stop sprawl while building more of it. It wanted to celebrate multiculturalism while maintaining exclusion. And as the city expanded outward, environmental language helped justify it all. The sagebrush became a symbol, not of what was protected, but of what was being lost underfoot.

The Racial Geography of Growth

The story of Albuquerque’s growth is a story of encoded exclusion. It didn’t start with zoning. It started with redlining and racial covenants.

1930s Home Owners’ Loan Corporation maps divided the city into color-coded investment zones. Neighborhoods like South Broadway and Barelas; dense, walkable, and largely home to Hispanic, Indigenous, and Black residents, were labeled “hazardous” or “definitely declining.” These red zones were cut off from lending and infrastructure. Over time, they became targets: for neglect, for clearance, for erasure.

Growth was never neutral. It was mapped onto race. And nowhere was that more evident than in the widening rift between the Valley and the Heights.

As early as the 1950s, tensions over infrastructure revealed deep geographic and ethnic divides. In 1959, the city proposed a flood control project through the Sandia Conservancy District to protect neighborhoods near the river; largely Hispanic, working-class communities long vulnerable to seasonal flooding. But the solution required tax increases citywide. Heights residents, mostly Anglo and middle-class, protested. They argued they would see no benefit from the project, despite the fact that upstream suburban development had worsened runoff into the Valley. The Property Owners Protective Association, formed to fight the tax, framed the issue as fiscal fairness. But the subtext was clear: we shouldn’t have to pay for their problems27.

The issue wasn’t just about water. It was about whose needs counted. And time and again, it became clear that the Valley’s needs did not.

That divide hardened as the city expanded. In 1965, a proposed gas tax to fund road construction, primarily in the expanding Heights, was defeated, largely due to opposition from Valley precincts. In the Heights, residents demanded new infrastructure, but opposed redistribution. In the Valley, residents had endured decades of underinvestment and began to resist footing the bill for expansion they hadn’t asked for.

These weren’t just policy disagreements. They were battles over belonging—fought in the language of taxation and infrastructure, but rooted in race, class, and power. And as the city grew, those divisions deepened.

In 1969, as Albuquerque finally joined the national urban renewal movement, these same neighborhoods were placed under a microscope. South Broadway, once a vibrant community, became ground zero for displacement. Surveys conducted as part of the city’s Model Cities process found something remarkable: most residents wanted to stay. Even those living in homes labeled “substandard” said they’d rather repair than relocate28. They didn’t ask to be removed. They asked to be respected.

Albuquerque may have been spared the full devastation of urban renewal that gutted cities like Detroit or St. Louis—but the damage here was more targeted, and no less consequential. The neighborhoods it did hit were largely in the Valley: South Broadway, Barelas, and Santa Barbara-Martinez Town. Some, like Santa Barbara, were able to organize and resist the most aggressive proposals—blocking a planned Hall of Justice, a museum, and a new educational campus. But even those victories came at a cost. Large swaths of land were still bulldozed for road widening, intersection expansions, and infrastructure projects that rarely benefited the neighborhoods they disrupted. And as we explored in our piece on Interstate 25, the freeways were often routed along the edges of these same communities—creating physical barriers that cut them off from the rest of the city.

But the machinery of progress moved forward. Model Cities emphasized participation, but real power still lay with planners, engineers, and elite landowners. Decisions were made in boardrooms and ratified in public meetings few could attend. And when residents resisted, they were accused of misunderstanding the plan.

Meanwhile, the Heights and the Westside boomed. These areas, whiter and wealthier, absorbed the lion’s share of housing investment. And when the time came to vote on citywide bonds for flood control or sewer expansion—especially those benefiting the Valley’s older, poorer, and browner neighborhoods—they often said no. Bond failures in the late ’70s and early ’80s stemmed directly from new homeowners unwilling to “pay for someone else’s problems.”

By the late 1970s, bond failures to fund sewer and flood control projects were no longer isolated incidents. They had become symptoms of a broader civic fracture: a city unwilling to build equitably, and increasingly unable to imagine itself as a shared, holistic whole.

Growth was never neutral. It was mapped onto race.

But the fractures weren’t just political or infrastructural. They were spatial.

As single-use, low-density zoning became the dominant template across the city, it didn’t just dictate what could be built, it shaped who could live where. Detached homes on large lots, rigid separation of residential and commercial uses, and car-dependent street networks weren’t just aesthetic choices, they were tools of exclusion, functionally limiting access to neighborhoods for renters, low-income families, and anyone without a car (Transit, to be discussed in a future section, wouldn’t become part of the local debate until later).

The form itself was a filter and in a city where redlining had already cut neighborhoods off from capital, this new zoning regime hardened those lines into law.

These zoning codes emerged just as Albuquerque’s overt racial covenants were finally beginning to lose legal enforceability. Though often unenforced or quietly ignored, racial deed restrictions remained on the books in many neighborhoods well into the 1960s. Some of the city’s first postwar subdivisions—advertised with aspirational language about “neighborhood character” and “exclusive living”—were explicitly marketed to white buyers. Covenants barring Black, Hispanic, Native, or Jewish residents echoed the language used in cities across the country. It wasn’t until the federal Fair Housing Act passed in 1968 that such practices were formally outlawed.

But exclusion doesn’t vanish with legislation. It evolves.

In Albuquerque, exclusion evolved into form. The same postwar suburbs that once relied on covenants could now rely on code. Large-lot zoning replaced deed restrictions. Building setbacks replaced red lines. Public meetings, planning boards, and sector plans became the new battlegrounds for deciding who belonged.

The idea of community input, introduced in the Model Cities era, had been meant to elevate the voices of everyday residents. And in places like Santa Barbara, it initially worked—helping residents stave off harmful urban renewal proposals. But as that process became institutionalized, it was increasingly dominated by those with the time, resources, and property to show up. The same participatory tools that once empowered the vulnerable were quickly co-opted by the powerful. In the Heights, groups like the Property Owners Protective Association, and later, coalitions like the Westside Coalition of Neighborhood Associations (WSCONA) on the Westside, perfected this model. They organized to oppose taxes, stop development, and enshrine exclusion as public consensus. What began as a tool for justice became a shield for privilege.

The Silence in the Room

In theory, Model Cities invited everyone to speak. In practice, only a few were heard.

Zoning meetings, planning commissions, and council hearings became performance spaces for the privileged. Notices were mailed to property owners, not tenants. Hearings were held in the middle of the day or in remote locations. Community input was framed not as a conversation, but as a referendum—where showing up to oppose something carried more weight than speaking for change.

The result was structural silencing. Working people, renters, and immigrants were functionally excluded from the process that shaped their lives. The loudest voices claimed to speak for “the community,” but their community was often a cul-de-sac.

Toward the Next Phase: 1980–2008

The map was nearly filled in by the end of the 1970s.

The subdivisions stretched from the mesa’s edge to the foothills, spilling across arroyos and floodplains, wrapping around farmland and consuming the very vistas they once sold. From Princess Jeanne to Taylor Ranch, the city grew outward with an almost religious confidence in asphalt and acreage.

But something still wasn’t working.

The promises of modernism—mobility, efficiency, prosperity—had arrived in fractured form. Arterials clogged. Services lagged. Infrastructure sagged under the weight of expansion. Downtown, once the center of gravity, was hollowed out by parking lots and broken by the scars of urban renewal.

The very neighborhoods built to escape “blight” now invoked it. The language had shifted—from disease to disorder, from poverty to density—but the fear remained. Residents rallied to protect what they had, drawing lines on maps and calling them “character.” Apartments were suspect. Transit was a threat. Newcomers were welcome only at a distance.

Meanwhile, public processes designed to include were quietly excluding. Hearings became performance spaces for the already powerful. Silence hardened into policy. And somewhere in the shadows of a city built for everyone, the question remained:

For whom was it really working?

In the next era, that question would only sharpen.

The 1980s brought more growth and roads to the Westside, opening vast new frontiers of suburban expansion. The volcanic escarpment that once seemed to protect the city’s edge gave way to arterials and cul-de-sacs. Petroglyphs were fenced, buffered, and then bypassed. Rio Rancho, once a retirement experiment, became one of the fastest-growing cities in the country.

Albuquerque, too, continued to boom though never quite like Phoenix. The tension between expansion and stasis grew more visible. Growth was still desired, but increasingly on others’ terms. Zoning, once seen as a neutral planning tool, metastasized into a code of 1,200 zone-types, a labyrinth of contradictions30: harsh where flexibility was needed, toothless where clarity was required. Over time, it became one of the most byzantine and reactive codes in the country—a monument to a city trying to answer competing questions with opposing tools.

The Comprehensive Plan adopted in 1975 promised direction. Instead, it sparked a new kind of battle: not over whether to grow, but who got to decide how.

That’s where we go next.

Footnotes

- Albuquerque Journal, February 16th, 1962 ↩︎

- Albuquerque Tribune, July 26th, 1962 ↩︎

- Albuquerque Journal, October 3rd, 1965 ↩︎

- Albuquerque Tribune, October 22nd 1965 ↩︎

- Albuquerque Journal, October 13th 1965 ↩︎

- Albuquerque Journal, October 13th 1965 ↩︎

- Albuquerque Journal, July 30th, 1965 ↩︎

- Albuquerque Tribune, November 12th, 1968 ↩︎

- Albuquerque Journal, June 15th, 1956 ↩︎

- Albuquerque Journal, March 2nd, 1968 ↩︎

- Downtown Zone Study — Albuquerque Tribune – November 11th 1965 ↩︎

- Fighting Sprawl and City Hall Resistance to Urban Growth in the Southwest; Michael F. Logan ↩︎

- https://albuquerquemodernism.unm.edu/posts/cs20_princess_jeanne_park_albuquerque_nm.html#user-content-fn-18 ↩︎

- https://www.gaar.com/images/uploads/The_History_of_Albuquerque_-_Chapter_4.pdf ↩︎

- https://winrocktowncenter.com/who-we-are/history/ ↩︎

- Fighting Sprawl and City Hall Resistance to Urban Growth in the Southwest; Michael F. Logan ↩︎

- ibed ↩︎

- Albuquerque Journal, May 3rd, 1959 ↩︎

- Albuquerque Journal, October 14th, 1959 ↩︎

- Albuquerque Journal, July 14th, 1960 ↩︎

- https://www.gaar.com/images/uploads/The_History_of_Albuquerque_-_Chapter_4.pdf ↩︎

- https://acrobat.adobe.com/id/urn:aaid:sc:US:19716da8-d058-46f0-a34a-62e5cd2e3611 ↩︎

- Fighting Sprawl and City Hall Resistance to Urban Growth in the Southwest; Michael F. Logan ↩︎

- Neighborhoods at Crossroads | Taylor Ranch ↩︎

- Fighting Sprawl and City Hall Resistance to Urban Growth in the Southwest; Michael F. Logan ↩︎

- https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2024/01/housing-shortage-minneapolis-environmentalism/677165/ ↩︎

- Fighting Sprawl and City Hall Resistance to Urban Growth in the Southwest; Michael F. Logan ↩︎

- ibed ↩︎

- https://www.krqe.com/news-resources/map-racial-covenants/ ↩︎

- https://www.planetizen.com/news/2017/11/95986-albuquerque-overhauls-its-zoning-code-first-time-1970s ↩︎

Leave a comment