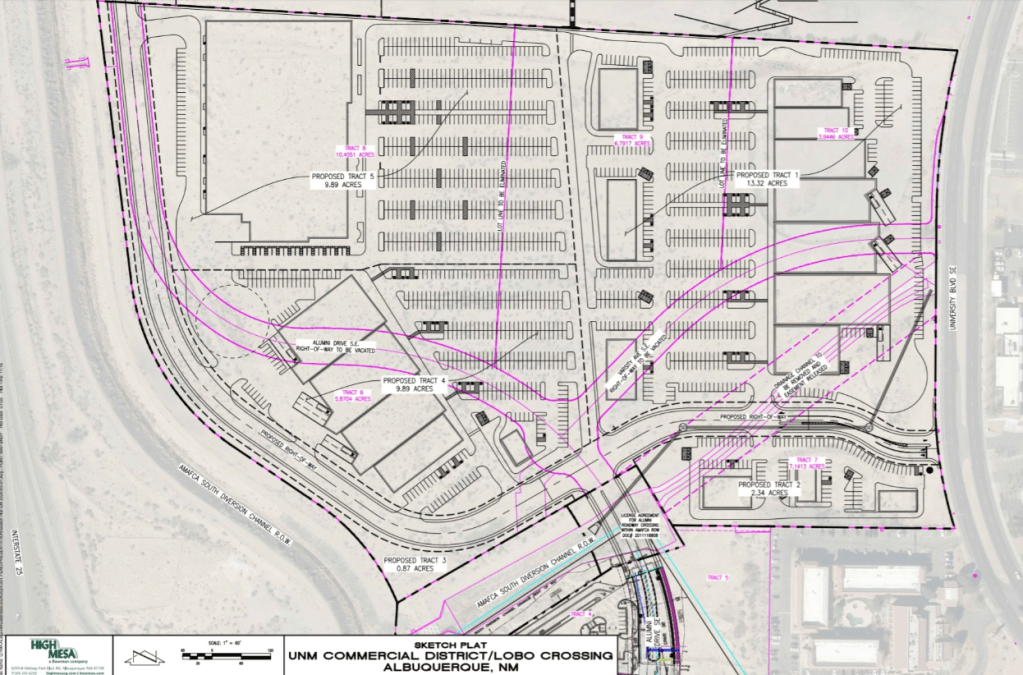

There’s a map tucked into a recent EPC filing that shows the future of UNM’s South Campus.

At first glance, it’s unremarkable: some rectangles labeled “proposed tracts,” a few looping roads, and rows upon rows of parking stalls. But look closer, and it tells a story. One of the most valuable, visible pieces of land in Albuquerque, a site between the university, the Rail Runner, the South Diversion Channel, and Downtown, is being handed over to a development pattern that could exist anywhere in the United States. It’s called Lobo Crossing, and if built as drawn, it will be a suburban shopping center surrounded by asphalt.

A Target. A few outlots. A handful of drive-thru pads. The kind of place you drive to once a week and forget about the rest of the time.

Not a place you live, or walk through, or remember.

A Wasted Opportunity

That’s what makes this moment so strange. UNM is simultaneously exploring upgrades to University Stadium, planning new facilities, and investing in the future of its athletic and academic footprint. The South Campus is on the table for reinvention, and could include mixed-use development. Yet the plan being advanced up to now feels decades out of step with the direction other universities are moving.

This land sits minutes from Downtown and UNM Main Campus. It borders existing infrastructure that could easily support a new kind of development—walkable, transit-ready, and deeply integrated with the university. It could be a bridge between campus and city, a genuine university district that ties UNM more closely to Albuquerque’s life and economy. It could also be a new, bustling Downtown neighborhood, providing homes, jobs, and businesses to the entire region.

Instead, the current proposal doubles down on a layout that isolates, flattens, and wastes space. If this sounds harsh, it’s only because the stakes are high. Every surface lot built today is a hole we’ll be trying to fill tomorrow.

University Boulevard, which cuts through the project area, could be one of the great urban corridors of the Southwest: a tree-lined boulevard with housing, classrooms, cafés, and bus rapid transit lanes linking students to Downtown, Main Campus and the Sunport. Instead, it’s being treated, still, as a stroad. Something to drive through, quickly, not arrive at.

The Mission Valley Example

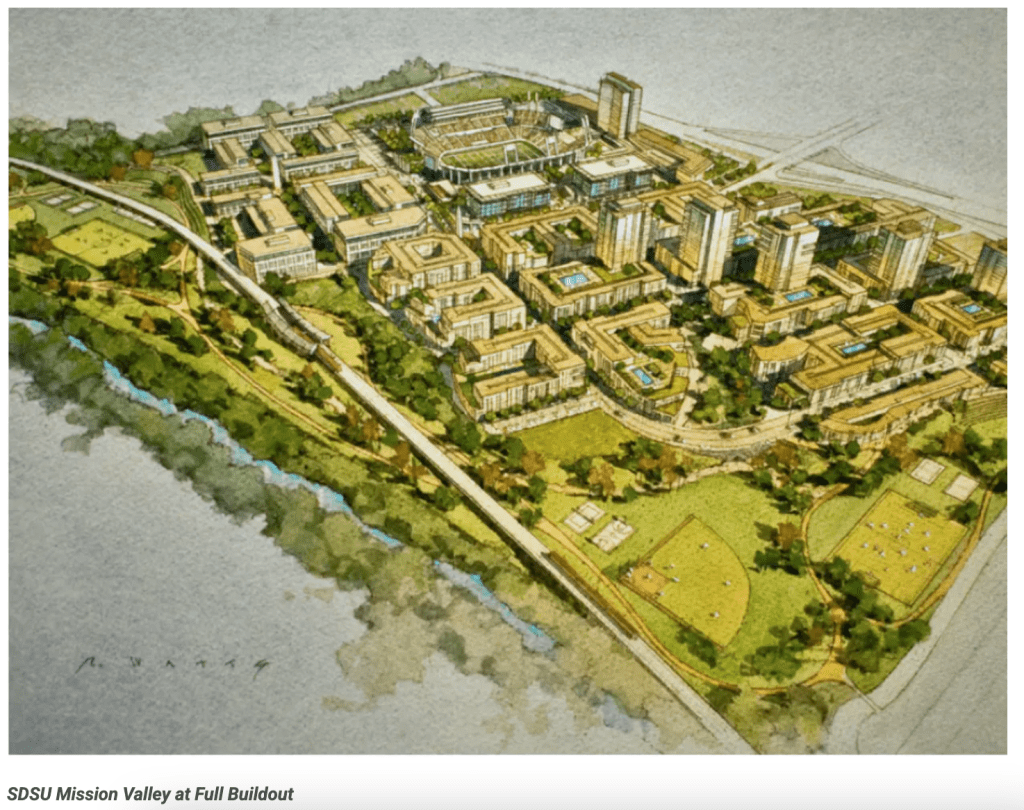

In 2020, San Diego State University took over the site of the old Qualcomm Stadium. They could have built another mall. They could have chased short-term lease revenue and parking contracts. Instead, they built a city.

Mission Valley is now becoming a 160-acre mixed-use campus: student and workforce housing, research labs, parks, classrooms, and small businesses woven together around a light rail stop. When it is completed, SDSU Mission Valley will include 80 acres of parks and open space, 4,600 market-rate and affordable housing units, 1.6 million sq. ft. of research and innovative space, 95,000 sq. ft. of retail space, and a hotel. It’s not just a redevelopment project but a statement of values. SDSU chose density, sustainability, and long-term community over surface parking and drive-thrus. The result is a neighborhood that will be far more alive.

UNM’s South Campus could be that. It’s the same idea: underused public land with prime (potential) access to transit and infrastructure. But where SDSU saw an opportunity to lead, UNM seems to be settling for less. Mission Valley, called a “car sewer” by Streetsblog, has many of the same issues as the South Campus area of UNM. Close proximity to amenities and infrastructure make it ripe for change. Why not seize the opportunity as SDSU, has?

What It Could Be

It’s not hard to imagine something different. Picture University Boulevard transformed from a high-speed arterial into a true boulevard: wide sidewalks, shade trees, bike lanes, and a busway connecting the points north from as far as Rio Rancho, to Main Campus, and then to the Sunport. Imagine housing above cafés and student apartments overlooking the stadium. Imagine academic buildings or startup labs spilling into the public realm, giving students and researchers reasons to cross between Main and South Campus, and to linger for entertainment, socializing, and shopping.

And then there’s the South Diversion Channel. Today it’s a barren utility corridor, fenced off and largely forgotten, carrying storm waters south but otherwise hard to remember. But it could be something remarkable: a greenway connecting South Campus to the South Valley, linking to trails and neighborhoods that have long been cut off by infrastructure in this area. A continuous walking and biking route would not only open up the site but also help bridge the physical and social gaps that have divided this part of the city. South Broadway and Downtown, for example, sit just to the west. The chasm created by the Interstate and the empty stretches of South Campus could use this project for urban repair and healing.

This kind of redevelopment would not only make South Campus more useful but also more human. It would give UNM the ability to model the kind of urbanism that students, staff, and faculty increasingly want to live in: dense, walkable, social, and sustainable. And? With a lot fewer cars and less space devoted to storing them.

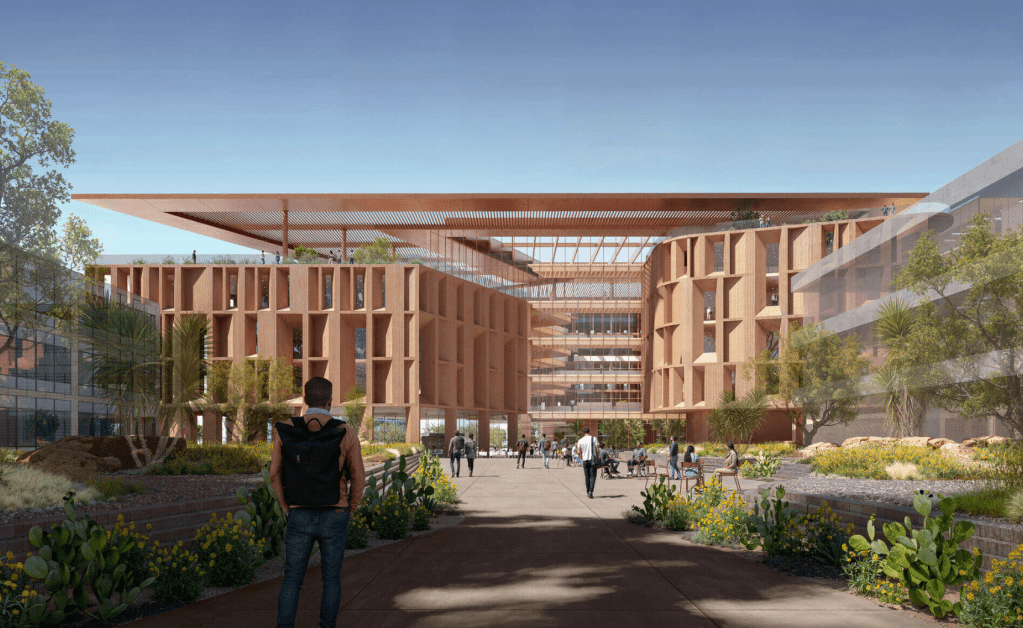

UNM Knows How to Do This

And here’s the part that stings: we know UNM can design beautiful, forward-thinking spaces. Just look at the new School of Medicine project on North Campus—designed by ZGF and McClain + Yu, or the new Fine Arts Center taking shape along Central Avenue. They’re elegant, compact, and distinctly Albuquerque. The architecture respects its place while embracing the future of education and care.

Why not bring that same ambition south? Why should one campus get the architecture of the 21st century while the other gets the parking ratios of 1987?

A Matter of Vision

The problem isn’t money or expertise. It’s imagination.

When universities develop land, they shape more than their own footprint: they shape the city’s. When done well, campus expansions become catalysts for growth and housing and public life. Done poorly, they become suburban voids that cut off neighborhoods from each other.

UNM has a chance, right now, to set a different example. A Target and a few chain restaurants might fill a few retail gaps, but they won’t move the city forward. They won’t contribute to solving our housing shortage or giving more space to students and visitors. They won’t build the next generation’s connection to the university.

But a mixed-use South Campus,one that embraces transit, housing, and design—could.

Let’s Build the City We Deserve

The story of Mission Valley isn’t that San Diego is richer or luckier than Albuquerque. It’s that their university decided to dream bigger. It understood that public land should serve the public good and that this, in turn, could serve the university while also being highly profitable.

UNM could follow that lead. It could show how higher education and urban design work together to create places that last. The land is already there. The timing is perfect. The stadium upgrades could be the start of something much larger—a campus that grows into a real neighborhood, one that belongs to both UNM and Albuquerque.

If the university and city choose to take that path, South Campus could become more than a parking lot with a mascot. It could be the moment we stop settling for less.

Leave a comment