How one Albuquerque neighborhood was shattered to make way for I-25—and why the state wants to do it again

In the spring of 1956, former Albuquerque Mayor and City Commissioner Clyde Tingley—one of the most influential political figures in the city’s history—stood firmly against the proposed I-25 freeway through the heart of town. “It’s the biggest foolish, jackass-type of thing I’ve heard of in a long time,” he said, calling for a caravan of Albuquerqueans to march on Santa Fe and demand answers from the governor. Tingley wasn’t alone in his concern, but he was unusually blunt. While many civic leaders saw the promise of federal dollars and equated freeways with modernity, Tingley saw clearly what the project would destroy: businesses, churches, playgrounds, homes. “It’s a shame and a disgrace,” he said. “The people of the city and county should rise up against it.”1

In the 1950s, Albuquerque was booming. It was one of the fastest-growing cities in the Southwest, flush with ambition and determined to cement its place in the modern American landscape. The 1940 Census counted 35,449 residents in Albuquerque. By 1950, the population had grown by 173% to 96,815 and officials were speaking about the city potentially reaching 250,000 by the end of that decade. City officials, engineers, and business leaders shared a common vision: progress through infrastructure. A city of tomorrow needed highways—long, wide, fast-moving corridors to usher in the automobile age and unlock miles of land for development north, south, and east of the city’s center.

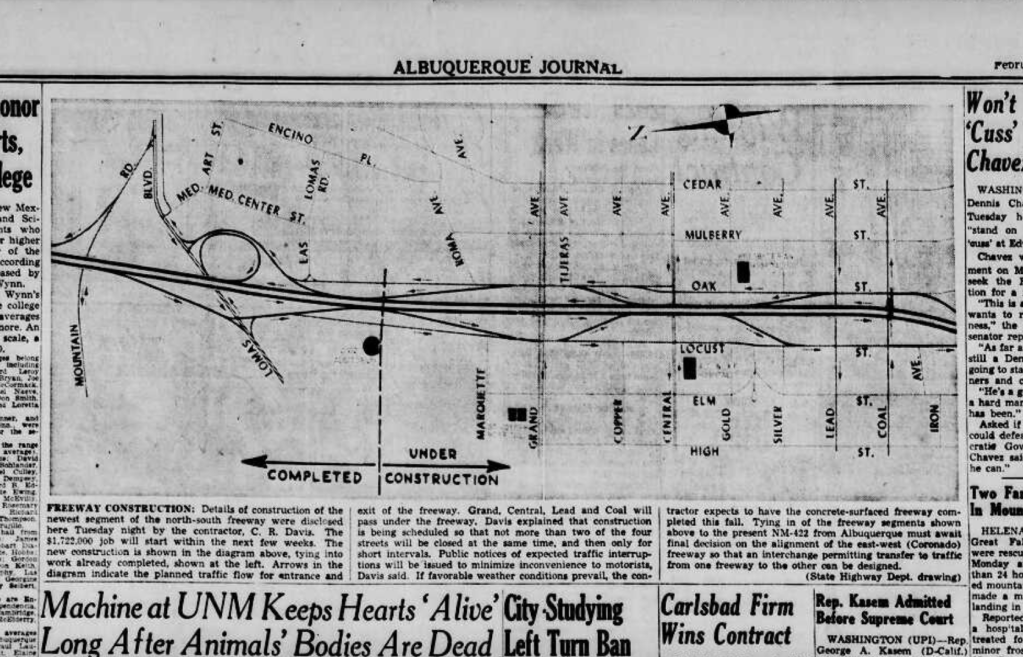

It was in that context, in 1956, that plans to extend State Highway 422—what would become Interstate 25—through the very heart of Albuquerque took form. It was hailed as necessary, even inevitable. A June 13th, 1956 Albuquerque Tribune article celebrated the Junior Chamber of Commerce’s unanimous resolution in favor of the route, quoting engineer Gordon Herkenhoff: “After research and study this route has proved to be most advisable as far as distance and expense is concerned.”2

To the business community, this was progress. The Jaycees went further, sending representatives to the State Highway Commission to urge “speedy action” on the extension. Local officials echoed the urgency. State Highway Engineer Lawrence Wilson called it “the last chance to get an adequate through route through the east part of Albuquerque.”3 And City Commission Chairman Maurice Sanchez declared that freeways were “bound to come unless the city wishes to remain antiquated.”

Tingley wasn’t alone in his critique, as not everyone was on board.

In a letter to the Tribune’s public forum, local resident W.M. Merrill called the proposal a “boondoggle of taxpayers’ money.” He wrote: “How stupid can our politicians and Highway officials get? Or, have they set themselves up as dictators, doing things their way…without letting the taxpayers—the working class people who elected them—[have a say]?”4

Merrill highlighted what the freeway would destroy: “The nine blocks, bounded by Marquette on the North, High on the South, Oak on the East and Locust on the West, there is a church, a public park, and a mortuary. These three things alone have benefited the well-being and welfare of the community for many years.”

He questioned the logic behind the project: “Now, if we had needed this highway for defense purposes, why didn’t the highway department route Highway 422 from Santa Fe to Albuquerque at a closer point of Sandia Base and Kirtland Field?”

Senator Dennis Chavez, though generally supportive of the freeway in concept, urged caution: “I wouldn’t want nine or ten blocks of homes, business houses, school houses, libraries and hospitals to be jeopardized without knowing what it is about.” He asked the Bureau of Public Roads to “hold back a little bit until we find out what the complaints are about.”5

These competing voices—business leaders urging acceleration, engineers promoting efficiency, residents pleading for their neighborhoods, and public officials issuing both warnings and endorsements—set the tone for a debate that still echoes today.

A Neighborhood Erased

The area taken for the freeway included parts of the Terrace Addition, a neighborhood platted in the early 1890s through the 1910s and marketed as one of Albuquerque’s most desirable new districts. A 1928 Albuquerque Journal advertisement celebrated its location as walking distance to Lincoln School, the state university, and Albuquerque High, and promised easy car access to Downtown via the newly paved Coal Avenue and an upcoming viaduct that would provide a second crossing of the railroad tracks. It was a textbook example of prewar urbanism—tree-lined, compact, and integrated with the city’s street and pedestrian network.

Terrace Addition was never wealthy, but it was stable and proud. Its homes were modest bungalows and Territorial-style multiplexes and courts, often owner-occupied, clustered around small grocers, parks, and schools. It embodied an era of neighborhood building that emphasized connection over speed, density over sprawl.

That neighborhood fabric also supported one of Albuquerque’s most vibrant Black communities in neighboring South Broadway. During the Great Migration, South Broadway became central to Black life in the city—offering both refuge from exclusion elsewhere and the foundations of a thriving local culture. According to long-time South Broadway resident Euola Cox, “Years ago, the housing situation was such that a Black person could not live in any area except the South Broadway area. Realtors made a conscious effort to sell houses to Blacks only where it was acceptable for Blacks to live. It was understood that if you were poor and Black, you lived in a certain part of the city, where the poor and Black lived” (Neighborhoods at a Crossroads).6 Out of that constraint grew a powerful and resilient community—rich in diversity, entrepreneurship, and civic life. The area housed barbershops, beauty salons, family-owned stores, churches, and gathering places that served not only Black families, but the broader integrated fabric of Albuquerque’s working-class east side.

That era ended with the arrival of NM-422, which would level large parts of Terrace Addition and separate neighborhoods like South Broadway and Huning Highland from neighborhoods to the east.

To the State Highway Department, the neighborhood was expendable. In justifying the route through the city’s core, Highway Commissioner Ralph Jones infamously praised the city’s “waistband” and called the freeway “a belt for Albuquerque’s waistline.” He argued it was “rather amazing” that the project would “disturb only eight or nine blocks that are really built up,” suggesting this limited destruction was a small price for progress. But to the residents of Terrace Addition, there was nothing fortunate about the bulldozers arriving at their door.

By the 1970s, the neighborhood had been hollowed out. Presbyterian Hospital paved over entire blocks for surface parking—advertising its 300-space expansion in 1972 as a sign of growth. The Technical Vocational Institute (TVI), now CNM, expanded across Lead Avenue, replacing homes and businesses with parking lots and institutional buildings. Coal and Lead were converted to high-speed one-way couplets, turning what had been residential corridors into auto sewers. Frontage roads flanked the freeway like a scar, reinforcing the physical and psychological divide between east and west.

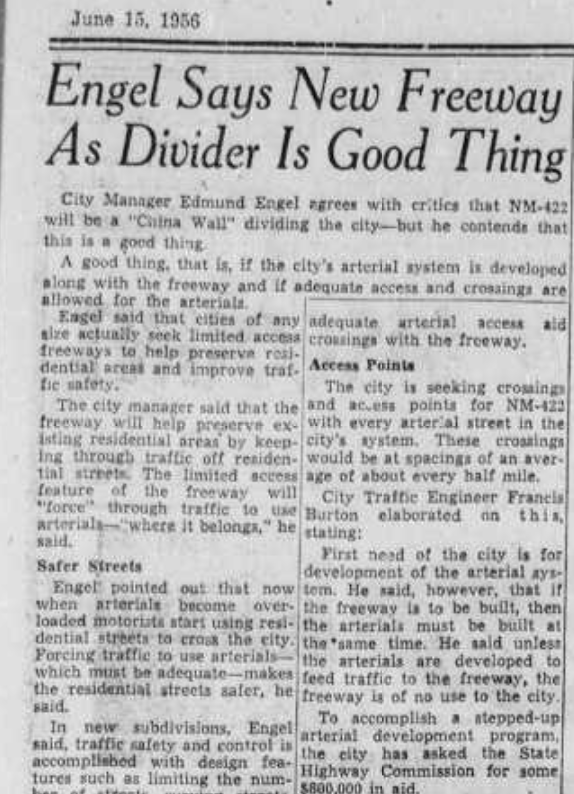

City Manager Edmund Engel acknowledged at the time that NM-422 would be a kind of “China Wall”7 through the city—but insisted this was a positive thing. He argued that limited access and separation from local streets would keep traffic on the freeway and out of neighborhoods, declaring, “The freeway will improve the traffic and safety situation.” He believed that “forcing traffic to stick to designated routes” would lead to safer streets, and that service roads would make the area “attractive for residential use.”

But Engel’s vision proved deeply flawed. In the decade following the freeway’s construction, Terrace Addition and its surroundings did not flourish—they declined. Entire blocks were razed for surface parking and institutional expansion. What had once been a walkable, mixed-use district became an archipelago of asphalt. Engel’s claims that access roads and limited crossings would improve the urban fabric were quickly disproven by the sharp increase in traffic speeds, disinvestment, and the loss of residents. The freeway did not preserve neighborhoods—it fractured them.

To make matters worse, the city doubled down on car-centric development. University Boulevard was realigned and widened, slicing through blocks of homes between TVI and Lomas Boulevard in the name of modernizing Albuquerque’s arterial network. Leafy neighborhood streets—Coal and Lead—were stripped of their original boulevardesque design and turned into high-speed, one-way arterials, prioritizing regional car traffic over local quality of life. What had once been a network of calm residential streets became conduits for commuters to bypass the very community they disrupted. As the Friends of Albuquerque Environmental Story noted in 2008, “The built environment of the Near Heights has, of course, continued to change, not always for the better. The demands of the automobile in our increasingly decentralized city, for example, radically altered the cohesion of older neighborhoods.”8

Silver Hill, Sycamore, and the remnants of Terrace Addition spent decades trying to recover from this trauma. Disinvestment followed displacement. Property values fell. Families moved out. And what had once been a thriving walkable district became a patchwork of vacant lots, institutional land, and vehicle infrastructure.

One of the clearest casualties of that decline was Lincoln School, a once-beloved middle school that stood as a rare example of integration in the United States’ segregated education landscape. Serving students from across the diverse neighborhoods of Terrace Addition and South Broadway, Lincoln brought young Burqueños together at a time when such schools were scarce. But after the freeway arrived, physically cutting the school off from its neighborhood and accelerating residential flight, its future began to dim. By 1970, just four years after I-25 opened, the city began considering closing the school despite vocal opposition from parents and community members. District lines were redrawn in an attempt to preserve it. But by 1974, the damage was done. Lincoln School was shuttered, and today, it sits boarded up within the APS maintenance yard—trapped between the freeway and Milne Stadium, a visible ghost of the community it once served.

This was not an accident: it was the cost of speed. The gospel of midcentury highway planning was simple: make it faster, make it wider, and cities will grow. Engineers insisted this was modernization. But the result was the opposite: disconnection, economic stagnation, and the atomization of community. Albuquerque paid the price for a promise that never materialized.

Today, we live in the shadow of that “value.” The very fabric of the Terrace Addition was sacrificed to chase speed, convenience, and federal money. And nearly 70 years later, we are still debating whether it was worth it.

A Second Act, or a Repeat?

Today, 70 years later, the state is once again preparing to reshape Albuquerque in the name of ‘safety’ and ‘efficiency.’ The I-25 S-curve expansion, planned at $400 million for more lanes and faster frontage roads, threatens to deepen the wounds it once opened. It may not demolish homes, but it dismantles livability.

Nowhere is this clearer than in the proposal for new frontage roads.

These aren’t like the narrow, local-serving roads that exist along some parts of the corridor today. The new frontage roads would be significantly wider, designed to carry fast-moving traffic—posted at 30 mph but realistically operating closer to 50 mph. According to project materials, they would push into Highland Park, narrowing the green space and putting high-volume roadways alongside what little remains of the community’s public realm. Just north of the park, the frontage road would cut directly beside Hotel Parq Central, once the historic Santa Fe Hospital, effectively re-traumatizing a site already damaged during the freeway’s initial construction in the 1960s and which took over 20 years to find new life after it finally stopped treating patients.

The hotel and park, both symbols of attempted neighborhood recovery and reinvestment, would again be placed in the shadow of car infrastructure. As one Downtown Albuquerque News9 article put it, “opponents see the frontage roads not as a compromise, but as a new intrusion—making the neighborhood less walkable, less livable, and more disconnected from the rest of the city.” The broader fear is not only that this mimics the mistakes of the past, but that it does so more aggressively, with wider roads and higher design speeds than before. “Let’s think about humans and survivability,” Strong Towns President Brandi Thompson told a meeting last December.

Opposition has emerged under the banner of Rethink I-25,10 a coalition that includes neighborhood associations from Huning Highlands, EDo, Raynolds, and South Broadway, alongside organizations like Strong Towns ABQ and urban policy advocates. Their critique mirrors the ones voiced in 1956: Who benefits? Who pays? And what are we sacrificing in the name of car throughput?

But unlike in 1956, today’s opposition is deeply informed by questions of equity, justice, and community healing. The wall-like infrastructure once praised by City Manager Edmund Engel as a tool for order and safety is now seen more clearly for what it is: a barrier. A line drawn through the urban landscape that often separates opportunity from disinvestment, wealth from poverty, and white neighborhoods from communities of color.

This isn’t just a hypothetical. The original construction of I-25 cut through and isolated South Broadway and San José—working-class neighborhoods that included one of Albuquerque’s most significant Black communities. The trauma of disconnection and displacement is still present, and the proposed expansion threatens to deepen the divide. The new lanes and frontage roads would not just move traffic—they would further reinforce the boundaries between who has been invested in, and who has been left behind.

Like so many midcentury highway projects, I-25’s original path mirrored a national pattern of targeting communities of color under the guise of progress. As TIME11 reported in the case of Ferguson, and as YIMBY Action12 has chronicled across cities, these “transportation upgrades” have left a legacy of segregation and economic harm.

And yet, in 2025, the same script is playing out. NMDOT engineer Summer Herrera claimed to DAN that “induced travel at the facility level will include traffic diverted from parallel routes,” dismissing broader induced demand by arguing that “this section of I-25 does not have sufficient routes parallel to it.” Her justification for the project’s safety benefits relied on a model derived from an industry manual and approved by the federal government, which she said “definitively concluded that the number and severity of crashes were significantly reduced” with the freeway’s realignment.

This framing echoes that of 1956, when Highway Commissioner Ralph Jones said the freeway would “weld the city together” and State Engineer Lawrence Wilson declared it was “the last chance” for a through-route—both relying on vague projections of future growth and dismissing public concern. Then, as now, officials used technical language and distant modeling to present the freeway as inevitable. But forecasts are not fate. As Robert Goodspeed, professor of urban planning at the University of Michigan, warns, this is how engineers “colonize the future”—using speculative data to preempt debate about what kind of places we actually want to live in.13

Models like NMDOT’s rarely account for the trip not taken. They don’t consider what happened when San Francisco’s Embarcadero Freeway was removed,14 or when Broadway in Manhattan was pedestrianized,15 or when Portland eliminated Harbor Drive.16 In each case, traffic simply disappeared or adjusted—contracting in response to reduced capacity. Traffic isn’t a liquid in a pipe; it’s a gas. It expands to fill the space given to it, but it can also shrink. Herrera’s statements—and the project’s modeling—rest on the assumption that traffic volume is static and inevitable, rather than shaped by land use, incentives, and investment.

These rationales aren’t just flawed—they’re familiar. In both 1956 and today, engineers tell us that the model demands action, that failure to expand is failure to plan. But in doing so, they bypass a fundamental question: What if the model itself is the problem?

Urban designer and Strong Towns founder Charles Marohn distinguishes between streets and stroads—a term he coined to describe high-speed, pseudo-arterial roads that fail at both mobility and value creation. Streets, Marohn explains, are places where people live, walk, shop, and gather. They build wealth and community. Stroads, on the other hand, are designed for speed but littered with driveways, stoplights, and turning movements that make them dangerous, inefficient, and economically destructive.

What’s proposed for the I-25 S-curve—wider frontage roads that carry high-speed traffic alongside homes, hotels, and parks—is worse than a stroad. It’s a freeway flanked by stroads, severing walkability and sucking vitality from the very neighborhoods Albuquerque hopes to revitalize. Instead of stitching our city back together, these roads would drive us further apart—socially, economically, and physically.

We must ask: Do we want more barriers—or more connections? More throughput—or more life on the street?

Because what we build next will answer that question—for decades to come.

Alternatives Ignored

Critics have proposed smarter, more future-focused alternatives. Instead of expanding the freeway, why not invest in transit? The Rail Runner could be upgraded to offer faster, more frequent service between Albuquerque and Santa Fe—for under $200 million, according to the legislature’s own fiscal report.17 For another $360 million, the entire corridor could even be electrified. NMDOT argues that widening the S-curve will reduce crashes by correcting “deficient curves,” and engineer Summer Herrera insists that induced demand won’t apply here because “this section of I-25 does not have sufficient routes parallel to it.” But this logic reflects a broader problem in how DOTs approach infrastructure—not as policy choices, but as engineering inevitabilities.

Herrera claims that “the evaluation definitively concluded that the number and severity of crashes were significantly reduced with correction of the deficient curves,” citing an industry trade manual approved by the federal government. But such statements hide behind technocratic language—framing the future as preordained, rather than shaped by values. As urban planning professor Robert Goodspeed is cited in “City Limits”, engineers often “colonize the future” by presenting their models as objective truth, when in fact they are extrapolations based on past car-centric behavior. They rarely consider the trip not taken—the ways people might drive less if we made transit faster, housing closer, or walking safer.

Treating traffic like liquid in a pipe, DOTs assume that more volume needs more space. But traffic behaves more like a gas: it expands to fill capacity, but can also contract when that capacity is reduced. Studies from VTPI, Vox, and Strong Towns all point to the same conclusion: building more lanes doesn’t fix traffic—it fuels it.

But none of that appears in the current plan. No mention of transit, no real investment in multimodal alternatives, no commitment to a carbon-reduction future. Just another massive investment in a car-only system that has already failed to deliver prosperity.

The False Promise of Freeways

From Dallas to Detroit, cities across the country are confronting the legacy of their freeway mistakes. Some, like Rochester, NY and Milwaukee, WI, have begun to tear down inner-city highways, reclaiming land and rebuilding community fabric. Albuquerque has the same opportunity.

As Strong Towns and other organizations have pointed out, traffic is not destiny. More lanes mean more cars. Between 1993 and 2017, U.S. cities spent $500 billion expanding highways—only to see congestion grow by 144%,18 far outpacing population growth. Highways are expensive, inefficient, and destructive when run through the core of a city.

Even in 1956, some leaders saw the danger. U.S. Senator Dennis Chavez said: “I wouldn’t want nine or ten blocks of homes, business houses, school houses, libraries and hospitals to be jeopardized without knowing what it is about.” He called for the Bureau of Public Roads to “hold back a little bit until we find out what the complaints are about.” His words remain remarkably prescient in a city still dealing with the consequences.

Meanwhile, City Manager Edmund Engel conceded that NM-422 would be a kind of “China Wall,” but defended it by claiming “this is a good thing” if proper crossings and arterials were developed. He insisted that it would “route freeway traffic to use the freeway through routes where it belongs” and called limited access “a value.”

City Commission Chairman Maurice Sanchez summed up the dominant view among officials: “If the city doesn’t take advantage of this opportunity, it would be a tragedy for the future of this city.”

The freeway did not unite Albuquerque as promised but fractured it. It did not preserve neighborhoods—it hollowed them out. It did not improve safety—it brought higher speeds, more crashes, and deeper inequities. The “Wall” metaphor became literal: a scar of concrete, isolating communities and severing opportunity. The vision he promoted—of a fast-moving, car-centric city—delivered congestion, disinvestment, and lasting trauma.

Today’s S-curve expansion rests on the same flawed logic. It won’t make I-25 safer. It won’t meaningfully reduce congestion. And it directly contradicts the state’s own climate, equity, and transportation goals. New Mexico has committed to reducing vehicle miles traveled and investing in multimodal transportation. Yet here we are, doubling down on the exact kind of infrastructure that makes those goals impossible.

This isn’t a forward-looking transportation strategy. It’s a monument to inertia—a $400 million bet on a 70-year-old mistake. We should call it what it is: a barrier to progress, disguised as progress.

A City’s Choice

In 1956, city leaders said I-25 would weld Albuquerque together. In truth, it cut it apart. Now, we face a second chance—not just to oppose a bad project, but to imagine something better.

What would happen if we stopped expanding highways and started expanding possibilities? What if, instead of hundreds of millions on concrete, we spent that money on housing, transit, bike networks, and public space? What if, instead of treating speed as the highest value, we prioritized safety, affordability, and community?

The decision to expand I-25 isn’t just technical—it’s moral. When engineers say, “if we don’t do this, we’ll sit in traffic,” they are presenting a model, not a mandate. They’re pricing out a future built for cars, not people. As Patrick Kennedy once told TxDOT: “These are not options. These are price tags.” What else could we do with $400 million? What else could we build?

The past cannot be undone. But the future isn’t written yet. Let’s not repeat the mistake of 1956 by sleepwalking into another generation of disconnection.

Clyde Tingley understood the true cost of the freeway—not just in dollars, but in lives, livelihoods, and the cohesion of community. While others raced to secure federal funds, he demanded the city pause and reflect. He offered a simple alternative: route the highway around Albuquerque, not through it. Save homes. Protect neighborhoods. Invest in the future, not its erasure.

We didn’t listen then. But we can now.

Today, nearly 70 years later, we face a moment just as consequential. The S-curve expansion is being sold with the same language of inevitability and technical necessity that justified the original freeway. But like Tingley, we must ask: Who pays the price? And what kind of city will we leave behind?

This isn’t just a debate over traffic or modeling. It’s a choice about whether we want to double down on the mistakes of the past—or finally learn from them.

Let’s not make Clyde Tingley’s warning prophetic twice.

Let’s join others in rethinking I-25. And let’s start reimagining an Albuquerque without it tearing through our core.

- Albuquerque Tribune, May 26, 1956 ↩︎

- Albuquerque Tribune, June 13th, 1956 ↩︎

- Albuquerque Tribune, May 28th, 1956 ↩︎

- Albuquerque Tribune, May 29th, 1956 ↩︎

- Albuquerque Journal, May 29th, 1956 ↩︎

- “Neighborhoods at a Crossroads: History of South Broadway and Kirtland Addition.” ↩︎

- Albuquerque Journal, June 16th, 1956 ↩︎

- https://albuqhistsoc.org/aes/s2nearht.html ↩︎

- Downtown Albuquerque News, May 22, 2025 ↩︎

- https://www.rethinki25.org/ ↩︎

- https://time.com/3636171/road-to-ferguson-freeway/

↩︎ - https://yimbyaction.org/blog/broken-legacies-ongoing-impacts-of-racist-urban-renewal/

↩︎ - “City Limits” Megan Kimble ↩︎

- https://www.cnu.org/what-we-do/build-great-places/embarcadero-freeway-removal ↩︎

- https://www.c40.org/case-studies/c40-good-practice-guides-new-york-city-broadway-boulevard-project/ ↩︎

- https://www.cnu.org/what-we-do/build-great-places/harbor-drive-removal ↩︎

- https://ti.org/pdfs/Rail_Runner_Progress_Report.pdf ↩︎

- https://nextbigideaclub.com/magazine/surprising-social-costs-american-highways-bookbite/50129/#:~:text=This%20is%20known%20as%20induced,percent%2C%20significantly%20outpacing%20population%20growth. ↩︎

Leave a reply to Carlos Cancel reply