Part One

In the Manner of Progress

The idea that a city might be planned rationally, deliberately, even morally, is a relatively new invention in the American West. Before zoning, there was ambition and grit. Before regulation, there was exclusion. And in places like New Mexico, exclusion wasn’t just cultural—it was codified in land.

This is a story of how land use in Albuquerque evolved not to promote growth, but to control it; turning a living, organic city into a managed landscape shaped by power, fear, and legal formalism.

Where land once grew communities slowly, lot by lot, hand by hand, our modern codes now attempt to freeze it in place with dire consequences.

Long before Albuquerque had a zoning code, long before it had even been named, people built places with intention. At Chaco Canyon, at Taos Pueblo, and in countless other Indigenous communities across the Southwest, land was not subdivided in the way we subdivide it presently; it was shared, adapted, and reused across generations. Homes clustered for mutual support. Commons served as places of ceremony, agriculture, and trade. Public and private space were far more fluid than how we understand them today. The result wasn’t sprawl, but compact, resilient, collective living.

The Spanish land grant system partially carried this logic forward with plazas and shared ejidos, though the seeds of commodification had already been planted. Under U.S. control, those seeds bloomed: into private titles, formal codes, and a growing suspicion of anything communal. Zoning didn’t invent the hierarchy of land, but it gave it bureaucratic precision. It erased irregularity. It imposed categories: residential, commercial, industrial. What had once been organic, messy, and human became rational, mapped, and immobile.

And so we inherited a city where land is no longer a canvas for slow, shared growth but instead a grid of permissions and exclusions, shaped less by people than by policy. And we inherit a fight to restore the organic, community-centered forms of development that long shaped human cities, and continue to shape human cities throughout the world.

Before zoning, there were land grants. In Albuquerque, many of today’s neighborhoods sit atop former Spanish and Mexican grants; issued often not through consent, but through colonial reward. These grants did more than allocate land—they transformed it.

Issued first by the Spanish Crown and later by the Mexican government, these grants gave land to individuals, families, and entire communities to settle what is now New Mexico. Some were private, but many, especially in rural areas, were communal: shared lands known as ejidos, where residents grazed livestock, gathered firewood, and built towns1. In Albuquerque, these communities weren’t on the margins—they were the city. The Atrisco Land Grant, for example, predated the founding of Alburquerque in 1706 and stretched from the Rio Grande all the way to the Rio Puerco2.

In and around Albuquerque, the legacy is everywhere. After Tiwa people abandoned Alameda Pueblo, the land was granted in 1710 to Captain Francisco Montes Vigil as a reward for military service. Two years later, he sold it to Juan González, whose livestock corrals across the river gave the village of Corrales its name. This was how the land changed hands—not in ceremony, but in paperwork. Not with treaties, but with transactions.

In 1712, a 70,000-acre grant was made to Captain Diego Montoya. It passed to his widow, Elena Gallegos, and eventually to her son. The grant stretched from the edge of Sandia Pueblo to the boundaries of the new Spanish villa that would become Albuquerque. It reached from the river to the mountains. Strips of farmland were divided for irrigation. The commons in the East Mesa were used for grazing. Over time, the heirs sold parts off. What remained—7,761 acres—was transferred to the City of Albuquerque in 1982 and then turned over to the U.S. Forest Service. The land is now part of Cibola National Forest.

Much of the North Valley followed the same pattern. Ranchos de Albuquerque. Los Griegos. Los Gallegos. Los Montoyas. Los Poblanos. Names passed down, mapped out, and codified. What had been sovereign Indigenous land became colonial reward, then family inheritance, then federal asset. A city grew on top of that layered ground.

But this land was not empty. These grants were issued over ancestral and sovereign Indigenous territories. often without consent. Pueblos were displaced or constrained. Nomadic and semi-nomadic tribes, like the Navajo and Apache, were pushed further to the margins. Some grants were explicitly intended to serve as military buffers between Spanish settlements and “hostile” Indigenous groups, embedding conflict and conquest into their very design. So while land grants can be viewed as communal, even egalitarian, especially within Hispano settler communities, they were also colonial tools—part of a long continuum of Indigenous dispossession.

Then, in 1848, the direction of dispossession flipped. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo of that year promised to honor these grants. But in practice, most were ignored, misclassified, or carved up by speculators. Entire communities lost their rights to land they had stewarded for generations. Federal courts ruled that commons belonged not to the people, but to the U.S. government. And the Forest Service, often seen today as a neutral manager of public land, became—through purchase, pressure, and policy—the inheritor of millions of acres once held in common.

But this betrayal wasn’t just bureaucratic, it was also deeply exploitative. The failure of federal authorities to justly honor Spanish and Mexican land grants opened the door for a new wave of colonization: one led by lawyers, judges, politicians, and speculators who came to be known as the Santa Fe Ring. These men, some of whom served as territorial governors, surveyors general, and federal officials, used fraud, legal loopholes, and insider connections to seize control of vast tracts of land once held communally by Hispano settlers and their descendants while also narrowing indigenous land holdings, many of which had also been protected by Spanish and Mexican land grants.

Perhaps the most infamous among them was Thomas B. Catron, a lawyer and politician who would become the largest individual landowner in the United States. Through dubious legal mechanisms like partition suits, falsified genealogies, and the reclassification of community grants as private ones, the Ring carved up land that had once sustained entire villages. Surveyors general tasked with protecting land rights were themselves active speculators. And as the courts consistently sided with these interests, land slipped away—parcel by parcel, under the guise of law and progress.

The result wasn’t just lost acreage. It was a long memory of being dispossessed by systems that claimed to be rational. Institutions that promised order, but delivered exclusion.

The point isn’t to collapse one history into another but to name the continuity. Before zoning could exclude with setbacks and codes, the land had already been divided by other means. Not just taken, but reassigned. Formalized. Repackaged as order.

This legacy matters. It built a foundational mistrust of institutions—especially those that claimed to be neutral while reshaping land and power. The lines drawn in the name of “progress” rarely felt like progress to those being pushed out or corralled.

Like so many American cities, our city built its geography of inequality not just through racism in the abstract, but through codes, ordinances, and plans—layered and legal, designed and defended.

This is not a story of villains. It is a story of systems. And it begins not with a bulldozer or a blueprint, but with excited conversations in conference rooms, and a city convinced it was simply planning for the future and keeping up with the American march of progress.

So when zoning finally arrived in Albuquerque, first as a conversation in the 1920s, and then as law in 1953, it didn’t emerge in a vacuum. It came layered atop centuries of dispossession, wrapped in the language of order but steeped in a history of exclusion. The tools were new. The logic was not.

The Arrival of Zoning Ordinances

In 1887, in Yick Wo v. Hopkins3, the Supreme Court ruled that San Francisco could not selectively enforce a laundry ordinance to target Chinese business owners. That decision, technically about fire safety and wooden buildings, was a rare recognition that race and regulation had become quietly fused. But it didn’t last.

As Yoni Appelbaum details in Stuck4, the next chapter began in Modesto, California, a city that, facing pressure from white residents, quietly restructured its municipal code to keep its Chinese population and their laundries locked into a specific district. The law didn’t mention race. It didn’t have to. The justices upheld it, and with that approval, a door opened. Zoning—land use by another name—could now do what explicit racism no longer could. It became the language of decorum. Of “neighborhood character.” Of safety, aesthetics, and order.

By 1916, Berkeley, another California city, had taken the baton. In response to a proposed boarding house for Black laborers near a white neighborhood, the city adopted the nation’s first single-family zoning ordinance5. The logic was straightforward: if you could restrict what kind of buildings were allowed, you could restrict who was allowed to live there—without ever mentioning who.

This model of exclusion quickly spread. Cities across California adopted zoning laws that divided space not only by use but by class and, implicitly, by race. San Leandro became a textbook case. It remained over 99% white deep into the 1970s, despite being surrounded by a rapidly diversifying Bay Area. Zoning did the heavy lifting. Apartments were banned6. “Neighborhood character” was protected. The signs in front yards today say “Hate Has No Home Here,” but when it came to affordable housing, new neighbors, or multifamily homes, the politics have said otherwise. Justice and change are only being discussed now, many years later.

Albuquerque’s trajectory was not identical—but it rhymed.

While California cities experimented with zoning in the 1910s and 1920s, New Mexico adopted its own form of racial control: in 1921, voters approved a constitutional amendment commonly known as the Alien Land Law, which prohibited Asian immigrants from owning land. There was little dissent. In fact, local papers openly celebrated the exclusion.

“It bars Japs and Chinamen, and not aliens that could become citizens,” read a September 14, 1921 editorial in the Albuquerque Evening Herald. “It should carry7.”

At a Farm Bureau meeting one month earlier, reported in the Albuquerque Morning Journal, local leaders encouraged each other to vote in favor of the measure alongside opposing new taxes and highway bonds. The “Japanese exclusion law,” as they called it, was treated as common sense—an administrative housekeeping matter, not the codification of racial subjugation8.

That law stayed in New Mexico’s constitution for over 80 years.

In her piece Albuquerque’s Racist History Haunts Its Housing Market9, Wufei Yu reminds us that exclusion in Albuquerque was not always loud. Sometimes it was subtle. In the early 20th century, the Chinese community in Albuquerque faced ordinances that targeted their businesses, limited their housing options, and pushed them to the city’s edge. As the city grew, so too did its appetite for “order”—which often meant removing those who did not conform to its imagined identity.

By the time Albuquerque adopted its first zoning code in 1953, the foundations had long been laid. A city that prided itself on multicultural heritage had already decided, quietly and often without protest, who counted and who did not.

Today, more than 60% of Albuquerque is zoned exclusively for single-family homes. Entire neighborhoods—some of them once redlined, others built as enclaves—remain effectively off-limits to those who cannot afford a detached house on a quarter-acre lot. The rules are written in the language of setbacks, lot sizes, and parking minimums—but their effects are not neutral. Some of these neighborhoods, dotted with vestiges of old corner stores, multiplexes, apartment homes, and neighborhood businesses, now find themselves fighting to relegalize what once made them vibrant. Their residents are told that mixed-use buildings are not “contextually appropriate”—even when the context in question was imposed by mid-century code, not community, and even when the neighborhood was platted in the 1890s, faces a major institution, or sits on a high-frequency transit corridor.

The irony is sharp. What was once taken away in the name of order is now being denied in the name of preserving it.

This history is not theoretical. It is not distant. It is embedded in the city’s maps, its housing prices, and its daily commutes. It explains why some neighborhoods thrive while others decay. Why some schools are full of resources and others are not. Why housing is scarce and new development so often protested.

The Promise of Order, The Fear of Change

There is a kind of optimism that always accompanies the phrase “up-to-date.” It suggests that modernity is neutral, that systems are inherently good if only they are new enough. In Albuquerque in the 1920s, “up-to-date” meant something very specific: clean streets, orderly neighborhoods, electric signs only in the right places. It meant being like California.

In January of 1925, a man named C. O. Cushman stood in front of the Kiwanis Club at the Franciscan Hotel and gave a speech about zoning. It was the kind of luncheon speech that gets written up in the Morning Journal not because of what it said, but because of who was in the room. Cushman had once lived in Albuquerque but now sat on the zoning commission of San Leandro, California—a city already laying the groundwork for what would become one of the most segregated white suburbs in America.

He said Albuquerque should follow California’s lead. Cities out West, he explained, had discovered that zoning was essential to prevent “residence properties being depreciated in value by the erection nearby of filling stations and business structures.” San Leandro had zoned for single uses and was thriving. It was progress, he said. It was “strictly up-to-date.”

The crowd, which included Mayor Clyde Tingley and other city leaders, applauded10.

Cushman’s presence on San Leandro’s zoning commission wasn’t incidental. As previously mentioned, San Leandro would go on to become one of the most notoriously segregated white suburbs in postwar America; its zoning used not just to separate uses, but to exclude people. That one of Albuquerque’s own had helped shape that system, and then returned home to advocate for similar policies, ties Albuquerque’s zoning legacy directly to the national project of quiet exclusion. It wasn’t framed in racial terms—not publicly, at least—but the logic was the same: protect property values, limit change, and keep certain people out by controlling what could be built, and where. Zoning didn’t invent discrimination. But it offered a cleaner, bureaucratic way to carry it forward.

In the months that followed, local realtors began pressing for action. The New Mexico League of Municipalities lobbied the legislature to pass a zoning-enabling law11. Planners drafted proposals. Newsrooms editorialized in favor of “beautification” and “order12.” There was, as one 1927 article put it, a shared desire among New Mexico’s cities to copy from one another’s codes13—a quiet admission that originality was not the point. Uniformity was.

Zoning had arrived as a civic fashion. And like fashion, it masked its politics in form.

The draft ordinance created six zones: A and B were residential, C through E were for commerce, and F was industrial14. But the real lines—the ones that mattered—were not just on the maps. They were in the language: depreciation, disadvantageous businesses, incompatible uses. These were terms of art, imported from the West Coast. They allowed cities to keep apartments out of single-family zones, laundries out of downtown, “undesirables” out of sight.

In March of 1928, a promotional ad ran in the Albuquerque Journal for a new neighborhood: Terrace Heights. Buyers were told to act quickly: prices were climbing. The ad boasted proximity to the high school and the university, promised a boulevard with trees and a soon-to-be paved Coal Avenue. Most notably, it celebrated that the upcoming zoning ordinance would officially designate the area a “Grade-A Residence Section15.”

The phrase had the tone of a steakhouse menu, but it meant something sharper. This was how the future would be parceled out: not just by geography, but by code.

Clyde Tingley, ever the infrastructural futurist, supported zoning with a particular concern. It wasn’t just that buildings might go up in the wrong place. It was that buildings might not go up at all. Tingley feared that billboards, unregulated and profitable, would allow landowners to sit on vacant lots without developing them. “If we do not regulate the erection of billboard[s],” he warned, “we’ll soon have them on every vacant lot in Albuquerque… If the owner of a vacant lot can get enough money from the billboard people to pay his taxes, he will not build16.”

It was a kind of proto-YIMBYism, years before the term would be coined. Tingley believed land should serve the city, not sit idle. He wanted homes, not hoarding. He wanted growth—but with guardrails.

Yet the ordinance was delayed. Realtors objected to restrictions on downtown, 4th Street, and East Central. Editorial boards questioned the wisdom of codifying building heights. A January 1928 recommendation argued that the city shouldn’t move forward until it completed a comprehensive plan17. That, too, was delayed.

Even in its infancy, zoning revealed its cracks. A 1928 Albuquerque Journal editorial praised the city’s delay in adopting a zoning ordinance, warning that it had already become a political football—permits would be granted to the well-connected, and withheld from the rest18. Zoning was billed as a neutral tool to bring order and predictability but residents feared that permits were going to the favored few; others were left navigating a maze of restrictions that seemed to shift with proximity to power. The promise of zoning was order. The reality was discretion—rules broad enough to exclude and vague enough to bend. That tension hasn’t gone away. Today, the same cracks are visible—just papered over with new language. We still see codes written broadly and enforced selectively. We still hear appeals cloaked in concern but rooted in control. The script hasn’t changed. Only the players have.

Nearly a century later, echoes of these early debates remain. Where past residents feared that height limits on 4th Street, Downtown, and on Central would impose a “straitjacket” on growth19, today’s defenders of the status quo argue that loosening those limits will irreversibly scar neighborhoods. But beneath both eras lies a deeper discomfort—with the idea that cities, left to evolve, tend to grow organically: lot by lot, increment by increment, in ways that defy rigid control. Once dismissed as chaotic or undesirable, this kind of bottom-up growth is being reembraced today in the name of justice, affordability, and livability. And yet the reaction is familiar. Just as early zoning efforts sought to freeze the city into a particular form, modern opposition to reform often masks the same impulse: to hold back the natural rhythms of urban life under the guise of order, aesthetics, or equity.

When the zoning ordinance finally came to a vote in January of 1929, the backlash was theatrical. Citizens packed the meeting room. Voices rose. One newspaper described the ordinance as being called “everything from a property damager to a straitjacket.” The measure was tabled. Mayor Tingley told the room they could “go home and rest easier.” The zoning law, he said, had been “chloroformed.”

But the idea wasn’t dead. Just sleeping.

Read “City Zoning Ordinance Is Killed,” January 10, 1929

“labeled everything from a property damager to a strait-jacket, the proposed city zoning ordinance, after undergoing a terrific bombardment from citizens packed the room beyond capacity, was tabled by the city commission Wednesday night, ’till the taxpayer’s request its reconsideration.’ The motion to table the ordinance was made by Commissioner Chas Lembke and seconded by Commissioner Martin Riley and was passed unanimously by the city administrators on a roll-call vote. As Mr. Lembke finished his mention and before Mr. Riley had a chance to second it, the crows of persons who jammed the commission room broke into loud applause. There were shouts of ‘Thank you, Clyde,’ and ‘Thank you, Mayor,’ and ‘thank you, commissioners,’ as the gathering dispersed. “You people can go home and rest easier,” said Mayor Tingley, ‘and consider the ordinance chloroformed.’

What this first failed ordinance revealed was not just the tension between progress and preservation, but the limits of consensus. Everyone wanted order—but only on their terms. Everyone wanted growth—but not next door. The city, expanding rapidly onto the East Mesa, was beginning to confront an unsolvable problem that would define it for the next century: how to grow without changing.

It would take another quarter-century before zoning returned in full force. By then, the city would be in a different era. War would have transformed the economy. Suburbia would be ascendant. And the quiet codes of exclusion, perfected in places like San Leandro, would arrive in Albuquerque not as an innovation—but as a default.

Interlude: The City Without Zoning Still Found Ways to Exclude

Even as Albuquerque failed to pass a zoning ordinance in 1929, it continued to grow. Entire neighborhoods were developed, property sold, land subdivided—and exclusion, despite the absence of formal zoning, was alive and well. The rules were just enforced off the books.

Throughout the 1920s and ’30s, the city’s Black residents—many of whom had migrated from Texas or Oklahoma, or larger parts of the South during the Great Migration—were quietly but consistently denied access to most of Albuquerque’s neighborhoods. Real estate agents used “gentleman’s agreements” to steer Black families away from white areas, while property covenants written into deeds ensured that homes remained “whites only.”

The only place Black families could reliably buy land or homes was South Broadway, an area that became one of Albuquerque’s only historically Black neighborhoods not by design, but by exclusion. It was located near the railyards and industry—where land was cheaper and the environmental hazards higher. And yet, in this containment came community: churches, businesses, civic organizations, and Black cultural life flourished despite the boundaries around them. As longtime South Broadway resident Euola Cox recalled, “Years ago, the housing situation was such that a Black person could not live in any area except the South Broadway area. Realtors made a conscious effort to sell houses to Blacks only where it was acceptable for Blacks to live. It was understood that if you were poor and Black, you lived in a certain part of the city, where the poor and Black lived” (Neighborhoods at a Crossroads)20.

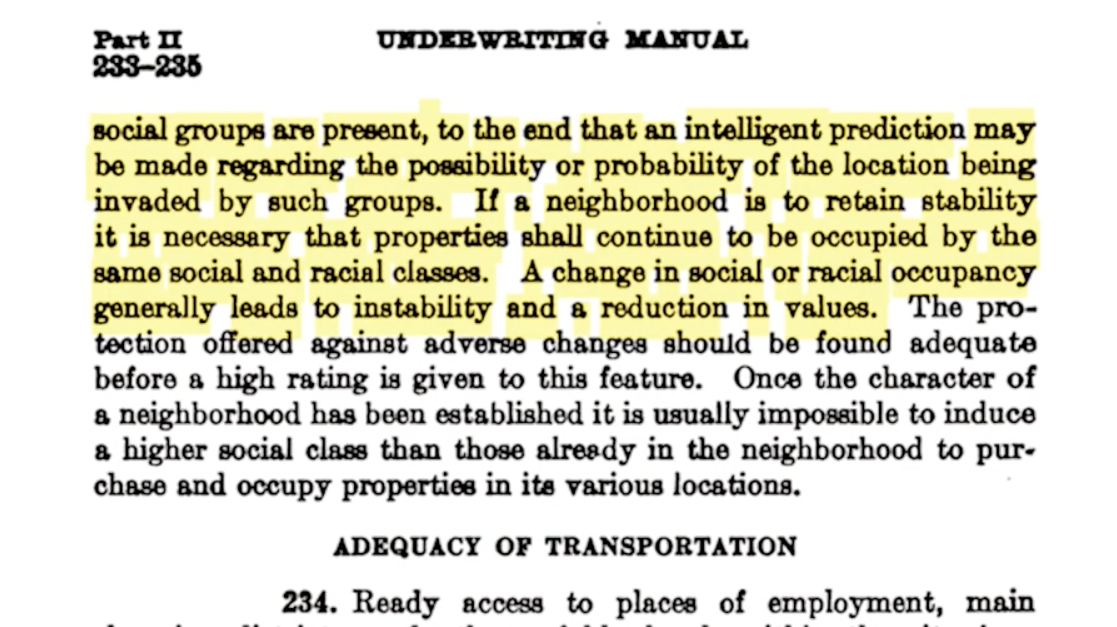

By the 1930s, exclusion was no longer just local custom—it was federal policy. The 1936 Federal Housing Administration Underwriting Manual, a document that shaped mortgage lending and housing construction across the country, made its position clear:

“If a neighborhood is to retain stability,” the manual stated,

“it is necessary that properties shall continue to be occupied by the same social and racial classes. A change in social or racial occupancy generally leads to instability and a reduction in values.”

This wasn’t subtext. It was instruction.

FHA appraisers and underwriters were explicitly told to factor in racial homogeneity when determining which neighborhoods deserved loans or public investment. This created a nationwide feedback loop of disinvestment and segregation and Albuquerque was no exception. Neighborhoods like South Broadway were either redlined or starved of resources, while newer, whiter areas on the East Mesa were promoted as sites of orderly expansion and “Grade-A” residency.

So while the 1929 zoning ordinance failed, the logic of zoning—of social separation under the guise of land-use planning—had already taken root. It would take years before Albuquerque would pass a formal zoning code, but its future had already been shaped: not by what was on the books, but by what was enforced behind the scenes.

The Ordinance That Tried to Freeze a City in Place

There is always something (surprisingly) theatrical about zoning hearings. The language is excessively dry: “nonconforming use,” “conditional approval,” “district boundary” — but the emotions are not. People show up for zoning hearings because they believe, often correctly, that it will affect what happens next door. Sometimes forever.

In Albuquerque in 1952, the drama of zoning was already well underway. The City-County Planning Commission, working with quiet urgency for nearly two years, had prepared a sweeping ordinance. City Manager Edmund Engel and Associate Planner Karl Ebel gave a three-part series in the Albuquerque Journal explaining why zoning was not just desirable but necessary. The future, they said, depended on it21.

But the future, as it turned out, was not going to cooperate.

On October 2, 1952, at a public meeting meant to educate North Valley residents about the proposed plan, things began to unravel. The crowd of over 140 people from the area between the Rio Grande and Edith Boulevard “indicated they understood little about zoning,” the Journal reported, “and cared less for it.” Misunderstandings were rampant: Would the city tear down homes? Would it annex land? Would it force people to move? The planners tried to explain. The meeting ended in frustration22.

A few weeks later, a new group emerged: the Bernalillo County Property Owners’ Association, organized for the express purpose of defeating the zoning plan. They said they had raised “a considerable amount of money” and would fight the measure “in its entirety.” They called it an infringement on the people’s right “to choose the disposition of their property by their effective vote.” It was a slogan that would reappear again and again in the decades to come23.

Today, groups like the Near North Valley Coalition and the District 4 Coalition fight zoning reform under the familiar banners of neighborhood protection, procedural integrity, and “appropriate development.” They call themselves defenders of place. But what they’re often defending are the very boundaries and regulations that attempted to freeze their neighborhoods in time.

The irony is hard to miss. Many of the earliest opponents of zoning feared it would erase the organic, mixed-use, incremental character of their communities. They saw zoning as a top-down imposition that would strip away local flexibility and property rights. And they were right. Zoning did flatten that complexity: segregating uses, banning corner stores, and elevating formality over function.

But today’s anti-reform coalitions have flipped the script. They defend zoning not as a threat, but as tradition, as something that must be preserved in order to protect the neighborhood. The very system their predecessors warned against has become, for them, a symbol of neighborhood identity.

They resist reforms that would allow the kinds of homes and businesses their neighborhoods once had. In doing so, they’re not preserving history, they’re preserving its erasure24.

Still, the city pressed on, as it still does. The final ordinance was drafted in mid-1953. Legal questions emerged almost immediately: could one part of the city be zoned without zoning the whole? This became urgent when Old Town, recently annexed, began fighting to stop a truck terminal by invoking the pending ordinance25.

So the commission sped things up. By August 8, 1953, details of the proposed code had begun to leak into the papers. It was the first time the public learned just how far-reaching the new regulations would be. Parking requirements for every type of building, from theaters to mortuaries. Lifetime grandfathering for non-conforming uses, unless destroyed by an “act of God.” Protections to keep industries out of residential areas—and, implicitly, people out of the “wrong” zones26.

The ordinance also included a lofty preamble:

“The purpose of this ordinance is to promote health, safety, morals, convenience, and the general welfare… to conserve and stabilize the value of property… to lessen congestion… to facilitate transportation, water, sewer, schools, parks and other public requirements.”

It was zoning as civics textbook. Zoning as moral ambition.

And yet, beneath the language of “comprehensive planning” was something else: a deep anxiety about change. As one pro-zoning letter to the Journal declared, “Zoning must be good—90% of people now live under zoning.27” That statistic was meant as comfort, but it read more like a sales pitch. The planners were still pleading.

The ordinance itself tried to make its case in moral terms. Section 2 stated that the purpose of the law was to “promote health, safety, morals, convenience and the general welfare… by regulating the use of land, height and bulk of buildings, extent of open spaces and the density of population.” It went on to cite the need to “prevent undue concentration of population,” “conserve and stabilize the value of property,” and “provide adequate open spaces for light and air.”

Each of these phrases carries a shadow. “Morals.” “Undue concentration.” “Stabilize the value of property.” These were not neutral planning goals. They were the hallmarks of a national zoning vocabulary forged in the crucible of racial panic, class segregation, and white suburban flight. And Albuquerque’s draft was no outlier. Its consultant, Dale Despain, proudly noted that it was the eleventh ordinance he had helped write. The implication was clear: this was a best-practice product, not a local experiment. A boilerplate for American stasis.

Today, defenders of restrictive zoning often argue it protects the “unique character” of neighborhoods or their cities. But that character was rarely organic. It was often imposed—standardized across dozens of cities, wrapped in lofty language, and weaponized to keep communities from evolving. What zoning preserved, more than anything, was a particular version of America: one built on separation, predictability, and the comfort of knowing who your neighbors would—and wouldn’t—be.

By August 25, the pressure reached a climax. The Journal predicted that the evening’s zoning hearing would draw “the biggest City Commission audience in the history of Albuquerque.” The ordinance shared the agenda with new tax proposals on cigarettes, gasoline, and sewer lines. Still, all eyes were on zoning28.

Clyde Tingley, now Commission Chairman, had pushed for splitting the hearings into four area meetings in larger quarters. He was denied. The chamber overflowed.

In the days before the hearing, endorsements came in from the Chamber of Commerce, the Board of Realtors, and the League of Women Voters. The Realtors urged “prompt passage.” The League praised the ordinance for “preventing overcrowding, keeping fire insurance rates down, and facilitating the obtaining of home loans.”

But others were less convinced. The parking requirements, in particular, were controversial. Downtown business owners opposed them, warning that mandates for off-street parking would discourage investment. A year later, their protests succeeded—parking mandates were stripped from the code29.

The ink was barely dry before the fights began. One of the first and most bitter emerged from what seemed like a mundane clash: the Albuquerque Bus Company had acquired land near Menaul and 6th, intending to build a new maintenance facility. But with the imposition of zoning, the parcel was suddenly—and retroactively—classified residential. What had been a routine land deal became a zoning violation30.

The company appealed. The city, not eager to go to court, relented and granted the zone change to “industrial.” But the damage was done. Neighbors were furious. They had expected the zoning ordinance to preserve their peace. Now, it seemed to authorize exactly what they had hoped to prevent. It was one of the first tests of the city’s new code—and it exposed a fundamental truth: zoning didn’t simplify land use. It made it adversarial.

A 1954 Albuquerque Journal editorial captured the moment: zoning, it argued, hadn’t clarified anything; it had put people against each other. What was supposed to bring order had instead created confusion, litigation, and resentment31.

It was one of the first tests of the city’s new code and it exposed a fundamental truth: zoning didn’t simplify land use. It made it adversarial. And that adversarial structure wasn’t a bug. It was the system.

Throughout the 1950s, similar stories played out. Disputes over zoning classifications. Appeals filed and withdrawn. Quiet parcels suddenly contested. The promise of zoning—that it would bring clarity, order, stability—gave way to something far more byzantine and bruising. The city, which had hoped to write its future on a clean map, found itself refereeing a growing tangle of grievances.

By the mid-1950s, even the professional class behind zoning was admitting the system had become warped. Dennis O’Harrow, executive director of the American Society of Planning Officials, told the International City Managers Association that zoning changes were no longer guided by plans—they were driven by pressure. “All over the country… you can get any zoning change you want if you just bring enough pressure,” he said. “The easiest place to get a change through is the board of zoning appeals. If the board stands pat, force the council. If the council is stubborn, the courts will help to slap it down.32”

Albuquerque officials saw themselves in his critique. What was once imagined as a tool for orderly growth had already become a battlefield of influence. The very promise of zoning—to remove politics from land use—was unraveling under the weight of its own contradictions.

O’Harrow’s synthesis was already ringing true, as the lawsuits had already arrived.

In 1955, the Albuquerque Trailer Court Association sued, claiming the ordinance was invalid. The problems were technical—missing enacting clauses, inconsistent section numbering—but they reflected a deeper unease33. The ordinance was too long. Too dense. One city employee told the Journal it could be written “better in three pages.” City Planner Dale Despain defended the document—56 pages long with a 158-word sentence that spanned two pages—as clear and readable, “as recommended by the U.S. Chamber of Commerce.34” He relented days later, promising to restudy the language35.

By 1956, more challenges came. Wasco T. Hedrick, an auto salvage operator on Second NW, sued after the city denied his request to rezone his land. The ordinance, he said, was “unreasonable, arbitrary, capricious, illogical, ridiculous, severe, and fantastic.” He called the penalties—$300 a day and 90 days in jail—“fantastic” in the legal sense: untethered from reality36.

Then came the federal case.

In 1957, a woman named Lorraine F. Mantle won a lawsuit in U.S. District Court declaring the city’s R-1 zoning unconstitutional as applied to her property on Ridgecrest SE. The court reasoned that proximity to Air Force and hospital traffic made single-family restrictions impractical. The result? Her property became an un-zoned island in a city obsessed with maps37.

It would take years for the city to resolve her status. Years without clarity. Years without justice.

Even the ordinance’s authors began to have regrets. Don Wilson, a former city commissioner who voted for the plan, returned to City Hall as an attorney seeking a zone change for a client. “I sometimes wish I hadn’t voted for the zoning ordinance,” he told the planning board. “The purpose of zoning is not to maintain a static condition.38”

That was, by then, exactly what zoning had become: an attempt to freeze the city in place. To put a frame around a living organism. To preserve order by stopping motion. The shared commons and growth of the old era had given way to the adversarial system that is familiar to us today.

By 1959, a new zoning code replaced the 1953 ordinance entirely, it having been invalidated for lacking the words “Proclaimed by the City Commission of Albuquerque.” It was similar in size and content—57 pages, pocket-sized—and perhaps a little humbler. But the lines it drew would shape Albuquerque for generations, or at least until 1965, when the city again adopted a new code.

Today, zoning still shapes who gets to live where, what gets built, and who gets to say no. From lawsuits over developments to debates over transit corridors, the same logics—fear, protectionism, control—resurface, cloaked in modern language. The old codes remain, not just in the law, but in the way we imagine what a city should be.

The fight had not ended. It had just been formalized.

Look for upcoming installments tracing how zoning evolved through parking mandates, car-first planning, suburban sprawl, and urban renewal—and how each layer of regulation made the code more complex, less just, and harder to change. We’ll also explore where reform is finally beginning, what zoning justice might look like, and how a different future is still possible.

- Struggle for Survival: The Hispanic Land Grants of New Mexico, 1848-2001

Author(s): Phillip B. Gonzales ↩︎ - https://albuqhistsoc.org/SecondSite/pkfiles/pk208landgrants.htm ↩︎

- https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/118/356/ ↩︎

- Yoni Appelbaum, Stuck: How the Privileged and the Propertied Broke the Engine of American Opportunity, Random House Publishing Group, 2025

↩︎ - https://www.kqed.org/news/11996229/berkeley-first-city-to-sanctify-single-family-zoning-considers-historic-reversal-allowing-small-apartments ↩︎

- https://justice.tougaloo.edu/sundowntown/san-leandro-ca/ ↩︎

- September 14th, 1921 – Albuquerque Evening Herald ↩︎

- August 10, 1921 – Albuquerque Morning Journal ↩︎

- https://www.hcn.org/issues/53-4/south-race-racism-albuquerques-racist-history-haunts-housing-market/ ↩︎

- January 8th, 1925 – Albuquerque Morning Journal – “ZONING LAW IS NEEDED, CUSHMAN TELLS KIWANIS

Former Albuquerque Man, Member of San Leandro, Cal., Commission, Gives Benefit of His Experience” ↩︎ - March 1, 1925 – Albuquerque Morning Journal – “Realtors talk of Zoning System – urge legislature to legalize system for cities that should like to use one” ↩︎

- July 24th, 1928 – Albuquerque Journal ↩︎

- May 10th, 1927 – Albuquerque Journal – “Municipal League met to discuss garbage collection as well as share notes on zoning laws” ↩︎

- November 29th, 1928 – Albuquerque Journal – “Zoning law passed first reading” ↩︎

- March 28th, 1928, Albuquerque Journal ↩︎

- March 17, 1927 – Albuquerque Journal – “City must allow city commission to regulate billboards, especially as city considers drafting a zoning ordinance as the state has now legalized” ↩︎

- January 4th, 1928 – Albuquerque Journal ↩︎

- March 14th, 1928 – Albuquerque Journal ↩︎

- January 10th, 1929 – Albuquerque Journal, “City Zoning Law Killed,” ↩︎

- “Neighborhoods at a Crossroads: History of South Broadway and Kirtland Addition.” ↩︎

- October 17th, 18th, and 19th, 1952 – Albuquerque Journal ↩︎

- October 2nd, 1952 – Albuquerque Journal – “Democracy Gets Loud, Off Subject At Zoning Meet” ↩︎

- October 26th, 1952 – Albuquerque Journal ↩︎

- March 27th, 2025 – Downtown Albuquerque News – “Neighborhood groups take city to court over ordinance that hampers their ability to launch development appeals” ↩︎

- May 12th, 1953 – Albuquerque Journal – “work on zoning law speeded to August 1st;” ↩︎

- August 8th, 1953 – Albuquerque Journal – “New Zoning Hearing Law Soon – Some Details of Document” ↩︎

- August 14th 1953 – Albuquerque Journal ↩︎

- August 25th, 1953, – Albuquerque Journal – “Zoning Ordinance Hearing Assures Crowded Meeting, Commission Slated To Consider New Tax Measures, Too”

↩︎ - July 8th 1954 – Albuquerque Journal – “Long Study Looms on Parking Plan” ↩︎

- August 17th 1954 –Albuquerque Journal – Zoning Entanglement Bound To Hurt Someone ↩︎

- August 17th 1954 – Albuquerque Journal – Zoning Entanglement Bound To Hurt Someone ↩︎

- December 1st, 1955 – Albuquerque Journal ↩︎

- June 29th 1955 – Albuquerque Journal ↩︎

- September 9th, 1953 – Albuquerque Journal – “Despain defends length of city’s zoning ordinance” ↩︎

- September 11th, 1953 – Albuquerque Journal – “Despain to Study Zoning Measure for Readability” ↩︎

- October 6th, 1956 – Albuquerque Journal – “Zone Ordinance Blasted in Suit In District Court” ↩︎

- March 9th 1957 – Albuquerque Tribune ↩︎

- April 21st, 1957 – Albuquerque Journal – “A former City Commissioner who voted for the zoning ordinance told city planners the other night he sometimes wishes he hadn’t.” ↩︎

Leave a comment