Between Walls and Bridges

From neon smut shops to sector-plan vetoes, the 1980s and 1990s revealed how easily Albuquerque scapegoated vice, codified localism, and forgot that the real cause of decay was its own planning decisions.

In this third installment of our series on the history of land use and zoning in Albuquerque, we trace the roots of contemporary NIMBYism and the anti-growth playbook. We look at how a zoning code swollen with sector plans failed to plan for people, how walls and bridges became symbols of exclusion and demand, and how a city that needed to act like a city instead doubled down on single-family sprawl. The cynicism toward planning that emerged in this era still shapes Albuquerque today.

Contents

- Between Walls and Bridges

- Introduction

- Neon, Sprawl, and the Birth of a Panic

- Martineztown: Walled In

- Richard Bell and the Taylor Ranch Uprising

- The Montaño Bridge: A Cottonwood Falls

- From Uprising to Demand

- The Coors Conundrum

- A Corridor in Crisis

- Dreams of Downtown Revival

- Barelas Stakes Its Claim In The Core

- Grand Plans, Partial Realities

- The Planned Growth Strategy and the Politics of Division

Introduction

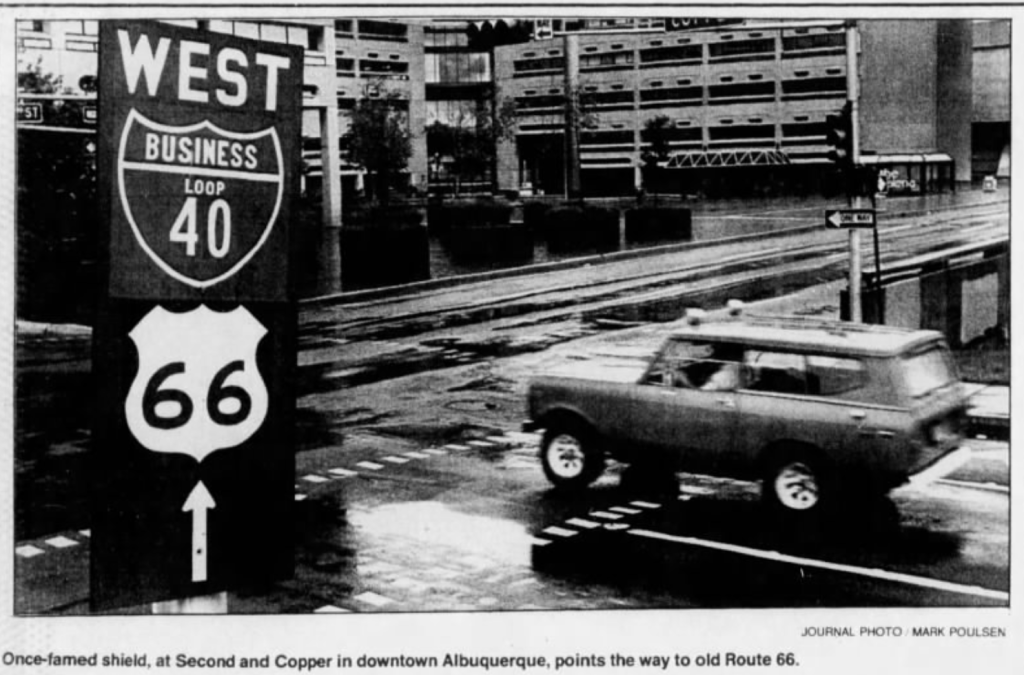

Drive east on Central in a Chevy Cavalier in 1985 and you knew, almost at once, the center had come undone. Route 66 was coming down from the maps, the signs stripped from their poles. The highway that had defined a generation was officially decommissioned, and its fading marquees made a neat symbol of the corridor itself: tired, gutted, past its prime. The road itself had become something else entirely: a chain of pawn shops, liquor stores, Pussycat Video glowing pink against stucco, the marquee at the old theater hawking Deep Throat as if it were just another Tuesday showing. Just as the old road was decommissioned, its motels, once neon waystations for travelers, had become rooms for rent by the hour. On the sidewalks, a trickle of pedestrians passed under buzzing streetlights, while the storefronts behind them emptied out one by one.

It was the era when Albuquerque’s Downtown was no longer the city’s Downtown, but a kind of shorthand for trouble. The optimism of the 1960s renewal schemes had curdled, leaving half-razed blocks and parking lots where old hotels once stood. Even the promise of “urban entertainment,” festival markets and glass-roofed plazas felt desperate, pitched against the reality that the gravitational pull of the city had shifted. The new centers rose not on Gold or Central but out along the freeway corridors, gleaming boxes in what had been desert, foothills, escarpment, or sagebrush a generation earlier.

And yet still, there was optimism. If not always Downtown, then in the sheer scale of expansion. The Westside subdivisions were marching toward the mesas, Taylor Ranch swelling with single-family homes. A city that had once been bounded by acequias and cottonwoods was pushing into what locals still called wilderness. Every bridge over the river was a fight, every apartment project a skirmish. By the time the Big I was rebuilt, the ancestral cottonwoods at Montaño had been torn asunder—first by chainsaws and hatchets wielded by vandals, then by arson, and finally by the bulldozers of construction crews. For many, one tree came to symbolize the city’s uneasy trade: growth on one side, loss on the other.

This set the stage for the next two decades: Downtown cast as decadent, Martineztown and Barelas resisting erasure, Taylor Ranch fighting against apartments and renters and fighting for bridges and sprawl, Coors Corridor tangled in its own rules. It was an era of contradictions, where civic leaders promised revival while residents fought to preserve views and trees, where the city sought order but produced patchwork instead.

By the early 2000s, Albuquerque had doubled down on its old mistakes even as it began to search for new answers. What follows is the story of that uneasy middle period—1980s to early 2000s—when Albuquerque’s past and future seemed to run parallel, never quite intersecting.

In the chapters that follow, we’ll trace this uneasy period through its defining battles: the porn panic on Central Avenue and the contested fate of Martineztown; the protests of Taylor Ranch and the symbolic fall of the Montaño cottonwood; the Coors Corridor Plan and the rise of “environmental” objections that masked exclusion; the repeated attempts to reinvent Downtown, from the threatened destruction of the Sunshine Theater to Jim Baca’s Theater Block and the Alvarado reborn; the Botanical Garden and Aquarium as signs of civic ambition; and the Planned Growth Strategy, which split Albuquerque’s politics into pro- and anti-growth camps.

Together, these stories carry us into the early 2000s, when the reconstruction of the Big I and the adoption of the Planned Growth Strategy revealed a city caught between its mid-century inheritance and the search for a better way forward.

Neon, Sprawl, and the Birth of a Panic

In 1985, the Route 66 signs came down.2 The highway that had carried Albuquerque’s mid-century dreams was struck from the federal map, and Central Avenue was left to announce its own decline. Pawn shops with barred windows. Liquor stores promising cut-rate whiskey. Pussycat Video glowing pink against stucco. The marquees on theaters lining the avenue pushing hardcore pornos like it was any weeknight film. Motels, once waystations for tourists, now rented by the hour.

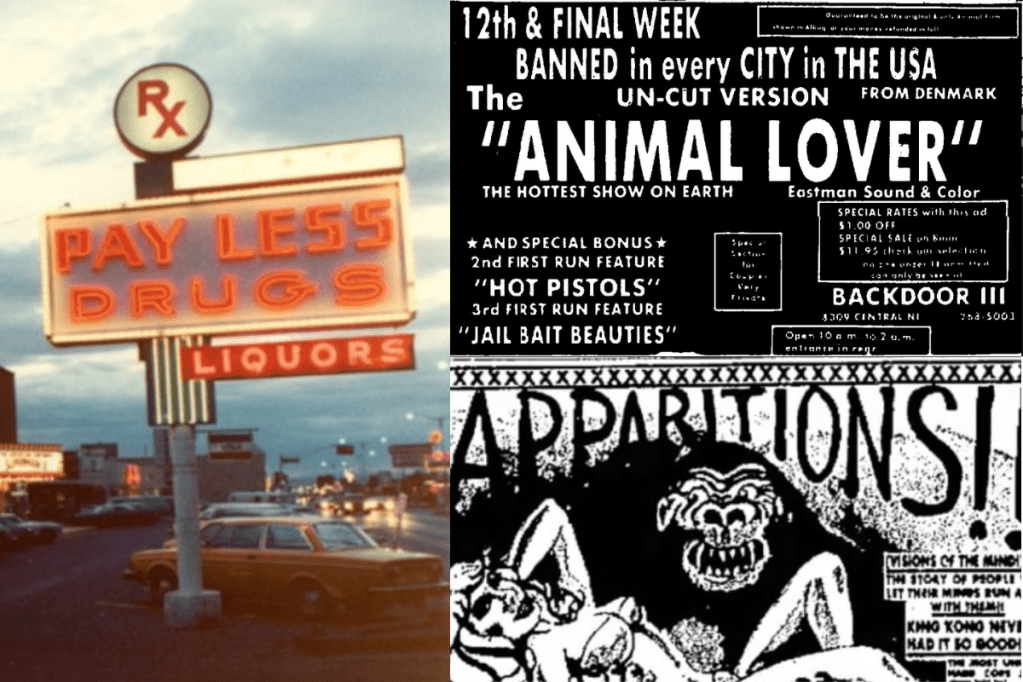

This was Downtown and the Central Corridor in the late 1970s and 1980s: neon against boarded facades, pornography both omnipresent and oddly banal. A 1975 Variety report counted eight full-time hardcore theaters, including a “porno-twin” on Central and the 24-hour Backdoor II, where Deep Throat played forty consecutive weeks. Ads ran daily in the Journal and Tribune, their illustrations inked over, a coded geography of discretion.

Porn flourished, but only in the vacuum left by flight and abandonment. Renewal schemes of the 1960s which brought pedestrian malls, convention hotels, and saw whole blocks razed had already failed, producing half-empty lots. The core was no longer the city’s heart but a shorthand for trouble. What filled the void were the businesses that could afford the rent: X-rated cinemas, adult bookstores, bail bonds, liquor. The porn marquee arrived after the decline had already set in, a timestamp more than a cause.

Nationally, the story was familiar. Times Square in the 1970s packed with grindhouses.3 Boston’s Midtown Cultural District hollowed out.4 Even Hollywood’s sign lost its final “O” during Los Angeles’s long slump5. City leaders blamed porn, yet the real work of hollowing out the core had been done by sprawl, disinvestment, highway building, and white flight. Albuquerque was no exception.

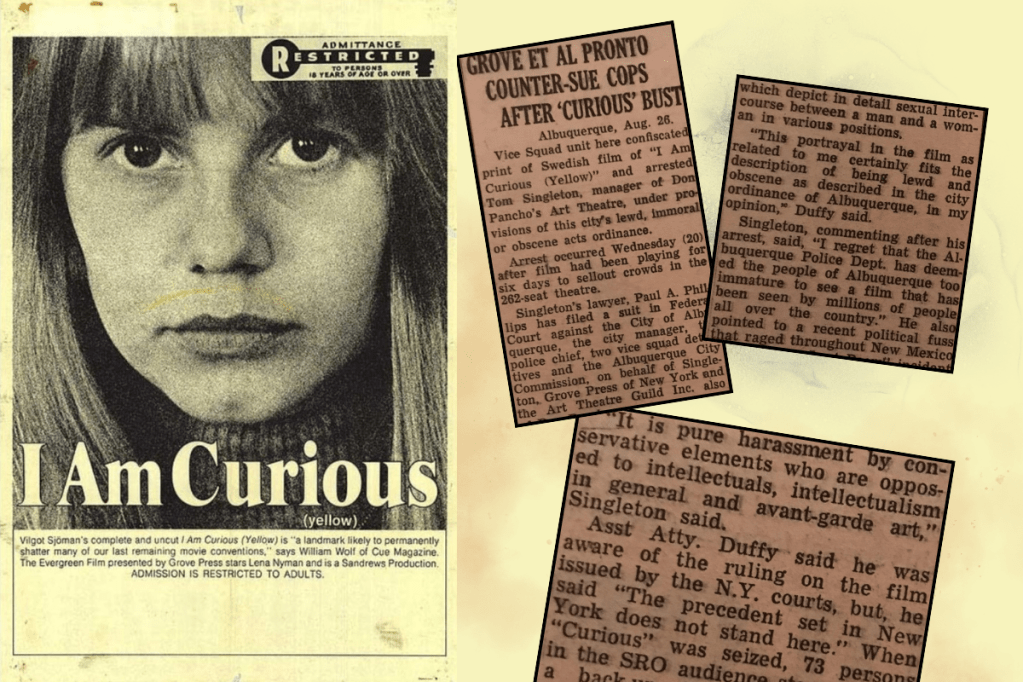

What made it distinct was the mix of permissiveness and panic. No enforceable obscenity ordinance, sporadic police raids which were sometimes theatrical, as in 1969 when Don Pancho’s Art Theatre was raided for showing I Am Curious (Yellow), its manager arrested under the city’s lewd-and-immoral code. Tom Singleton sued, calling the raid political harassment, a warning against “intellectualism and avant-garde art.” The line between arthouse and obscenity was porous, contested, weaponized.

By the mid-1980s, the tolerance snapped. Civic leaders cast adult businesses as urban cancers, even as national studies questioned the link to crime.6 A 1986 compromise brokered by Senator Manny Aragon kept some shops alive despite zoning violations.7 Two years later, Council voided it. In 1989, eight X-rated stores were shut down to a standing ovation.8

Councilors insisted porn shops bred crime, then proposed relocating them Downtown. If they were truly magnets for violence, the message was blunt: Downtown was expendable. The values of safety that shaped the suburbs did not extend to the city’s core. “In addition to restricting the bookstores to downtown, the zoning ordinance also prohibits them from operating within 1,000 feet of each other or within 500 feet of residences, schools, or churches.”9

In 1986, Chief Trial Attorney Manny Aragon cut a deal to keep eight porn shops open—Pussycat, Madam X, Pleasure Palace, Eros Arcade—while they challenged the city’s zoning code. In return, the owners agreed to dim their neon, add rear entrances, and tone down their signage. Aragon called it pragmatism, even as he admitted the pact made him “the scum of the earth” in some eyes.10

By 1988, the patience was gone. Councilors Pete Dinelli and Hess Yntema moved to void the agreement outright, calling it an “administrative arrangement” that had never been approved by Council or the mayor.

The councilors framed the 1986 deal as illegitimate from the start. Dinelli told the Journal: “We’re taking the position that the agreement with the bookstores was never binding on the city, because it is in violation of the zoning ordinance… I would prefer to see the bookstores reopened by a court order rather than ‘voluntarily allowing them to operate’ under the agreement.”11 Yntema added: “Passage of this resolution won’t solve all our problems, but it will create a more difficult environment for the pornographers.” In an earlier debate, he even suggested: “I think we should talk to Sen. Aragon about paying for any damages” if the city was sued.12

The moral panic found numbers. State Representative Bill Camp cited an Albuquerque Police Department study showing crime rates “seven times higher” in La Mesa, near two East Central porn shops, than in an adjacent neighborhood without them. The implication was blunt: porn shops weren’t just nuisances: they bred rape, robbery, and auto theft.13 Camp leaned heavily on statistics from the APD study to argue adult shops bred crime: “The empirical evidence is strong enough to show the bookstores are a strong cause for the increased crime.”14

But nothing in the reporting suggests this was rigorous research. It was an internal APD comparison of two neighborhoods, not a peer-reviewed study, and it ignored larger structural causes of crime, such as poverty, disinvestment, and the city’s own planning choices. The way city leaders latched onto these numbers showed how eager they were to pin decline on vice rather than on zoning and sprawl.

The numbers rested on the same shaky foundations as other “secondary effects” studies nationwide. By the late 1980s, cities across the country were citing one another’s research in a game of telephone, even when the underlying methods were “seriously and often fatally flawed.”15 The most commonly used reports, from Indianapolis, Phoenix, Los Angeles, and St. Paul, were riddled with problems: study areas weren’t properly matched to control areas, data were collected over too short a time to establish trends, and in many cases the “evidence” came not from crime logs at all but from biased surveys of nearby residents or real estate agents.

The Los Angeles study, for instance, admitted to “stepped-up” police surveillance around porn businesses, virtually guaranteeing higher arrest counts whether or not crime actually increased. The Indianapolis report asked real estate appraisers to speculate about hypothetical scenarios instead of measuring real property values. Phoenix offered no meaningful time-series data at all. These were not controlled experiments—they were anecdotes in statistical clothing fed by Reagan-era panic.

The irony is that the one study that did meet basic standards of rigor, conducted in St. Paul in 1978, found no link at all between adult businesses and neighborhood decline. When researchers compared census tracts citywide, the single consistent predictor of deterioration was the presence of alcohol-serving establishments—not bookstores or theaters. In fact, even areas with nude entertainment but no alcohol did not show the expected collapse.16

APD’s comparison of La Mesa to a neighboring tract was just a local replay of this pattern: no proper controls, no accounting for poverty or disinvestment, and no recognition that the real drivers of neighborhood instability (bars, liquor stores, absentee landlords, the city’s own planning failures) were already in plain view. The department’s “seven times higher” statistic was less a revelation of crime than a measure of Albuquerque’s eagerness to pin urban decline on vice.

On July 19th, 1989, the fight culminated. Council voted unanimously to close the eight remaining X-rated bookstores, greeted by a standing ovation from more than 250 opponents in the chamber. Mayor Ken Schultz joined the cause, proposing not only to shutter the shops but to ban adult ads from city newspapers altogether.17 The Journal recorded the scene: “The City Council voted unanimously Wednesday to shut down eight X-rated bookstores operating in violation of the zoning code, igniting a standing ovation from more than 250 pornography foes.” The resolution declared Aragon’s 1986 deal “null and void from its inception.”18

For Aragon, who had brokered the original deal, the backlash was deeply personal. He defended the agreement as “in the best interest of the city,” a way to avoid costly litigation while imposing limits on signage and operations. But the nuance was lost in the uproar. In his own words, the compromise made him “the scum of the earth in the eyes of some people.” The politics demanded a villain, and Aragon fit the part.

It was framed as crime prevention. In practice, it codified something else: if danger had to exist, it would be contained Downtown. The values of safety and community that shaped the suburbs did not extend to the city’s core.

By the time porn shops appeared, the center had already been hollowed by zoning that pushed growth outward. Zoning functioned by shunting growth outward to the foothills, to the Westside mesas, to subdivisions that multiplied while the core withered. Porn became the scapegoat, an easy stand-in for a city unwilling to admit that its decline was self-inflicted.

Like other cities, and despite evidence to the contrary, Albuquerque embraced the secondary-effects myth, codifying zoning as crime prevention when in fact it was zoning itself, through sprawl and disinvestment, that hollowed out the core.

As Charles Marohn has argued,19 the postwar development model was a kind of “growth ponzi scheme”: each new subdivision or strip mall generated short-term tax revenue but left behind long-term liabilities the city could never afford to maintain. The result was an illusion of prosperity on the edge, funded by extracting value from the center. In Albuquerque, the marquee over a porn theater became a convenient villain, but the harder truth was that the city’s own land-use regime was producing the very decline it sought to blame on vice.

Our leaders once explained away decline by blaming vice; now, similar narratives resurface when activists and leaders insist that investment itself is the danger—that new housing and commerce in Downtown neighborhoods or the International District will somehow create the very instability these neighborhoods already endure. But just as porn and peep shows did not topple Albuquerque’s center, gentrification rhetoric does not explain the deeper problems of disinvestment, exclusionary zoning, and the fiscal trap of sprawl. To move forward, the city must resist the comfort of scapegoats and confront the real structural choices that produce decline.

That also means acknowledging that the old tools of zoning are not the way out of the problems zoning itself created. As neighborhoods clamor for carve-outs and exemptions, from wealthy enclaves like Huning Castle to historic districts like Huning Highland, Barelas, or Nob Hill, the temptation is to double down on fragmentation and localism. Yet every exception only deepens the contradictions. The hard lesson is that the very way we build our environment under this regime leads inevitably to decay and stratification. Escaping the cycle requires not piling on more layers, overlays, or design standards, but re-orienting land-use rules toward inclusion and resilience.

Martineztown: Walled In

Council’s solution to the porn problem said as much about their view of Downtown as it did about obscenity. In one breath, leaders like Mayor Schultz, Councilors Dinelli & Yntema, and the Albuquerque Police Department, insisted that adult theaters bred crime, even violent crime; in the next, they proposed to concentrate them in the urban core. The contradiction was telling as It revealed a willingness to treat the city’s heart as expendable, a place where dangers could be contained. The values of safety and community that guided new subdivisions on the fringes of town stopped short of Central Avenue.

And yet, for neighborhoods folded into that same core, the future was not so easily written off. Martineztown, wedged between the railroad tracks, the interstates, and arterial roadways, was a Downtown neighborhood by geography, but never fully accepted as one by the city’s imagination. Then, as now, how Martineztown should develop—or whether it should develop at all—was a matter of constant dispute.

A Neighborhood in Two Minds

The split was not abstract. In the 1970s and 1980s, Martineztown residents were asked to weigh redevelopment plans that promised new housing and infrastructure. South Martineztown embraced the idea. Neighborhood spokesman and resident Richard Martinez was almost jubilant: “We’re very excited about the whole thing. This will improve the stature of Downtown living.”21 Frank Martinez, a Martineztown resident, community leader and redeveloper, described South Martineztown as “one of the few places in the nation where urban renewal means something other than bringing in the bulldozers… I guess I’m one of the few people who ever gets a chance to see a dream come true.”22

For the north, the view could not have been more different. Cipriano John Baca, 81 years old and a lifelong resident, rejected redevelopment outright: “This is the real Martineztown…this is where you have the same people, generation after generation.”23 To him, continuity mattered more than the city’s promises. A Journal story at the time put it bluntly: “For the residents of South Martineztown, a dream may have come true. For the residents of the north, a dream has yet to materialize.”24

That divergence became a hallmark of planning in Martineztown. For every plan that promised revitalization, another group of residents feared displacement. And as years dragged on, even supporters grew skeptical. Frank Martinez later admitted frustration: “The basic attitude of the residents is one of consternation…they’re somewhat dubious that anything will ever happen.”25

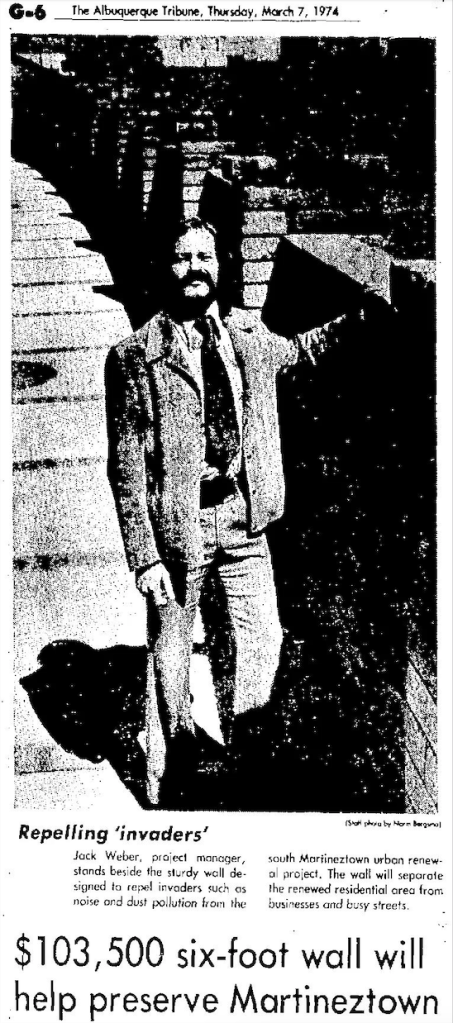

Wounds and Walls

Even where redevelopment did come, it came with scars. South Martineztown was rebuilt with new townhouses, but it was walled in. Concrete barriers rose along Lomas, Broadway, and Grand Avenue (later Martin Luther King Jr. Avenue), justified as buffers against traffic. They were meant to shield residents from the ceaseless flow of commuters driving in from the suburbs each morning, cars streaming off the interstates and into Downtown offices.

The walls were more than barriers to pollution and noise. Rather than heal the wounds left by road widenings, they hardened them. They denied Martineztown direct connection to the city that surrounded it. Where once you might have walked into Downtown to shop or to work, the walls blocked those routes. They told residents they were separate, enclosed, and perhaps most damningly, expendable.

Most of those walls still stand today, a stark reminder of how the city “protected” Martineztown by sealing it off. They mark the boundary between a neighborhood struggling to persist and a Downtown where city leaders were willing to concentrate (supposedly) crime-inducing “smut.” What the city called protection functioned as containment..

The same mentality shaped the streets themselves. City and state planners came to see Broadway and other thoroughfares not as main streets but as high-speed conduits funneling commuters into the core. In the process, Martineztown residents were denied the chance to build the kind of mixed-use homes, compact development, and businesses that thrive along healthy urban corridors. Instead, they were left encircled by stroads—dangerous, overbuilt hybrids of street and highway27—that cut them off from the fabric of the city. As Albuquerque enters a new era of urban investment, these choices remain cautionary. If we are to ensure that all Burqueños have the economic and social mobility they deserve, we must remember that walls and stroads didn’t protect Martineztown; they cut it off from opportunity, revitalization, and mobility.

Contested Belonging

The disputes over Martineztown’s identity were not new. For decades, residents had fought over whether the neighborhood was truly part of Downtown. Some embraced the designation, hoping it would bring investment. Others rejected it, recalling how being “part of Albuquerque” had meant road widenings, demolition, and neglect.

This duality mirrored the larger urban story. Just as Albuquerque’s leaders blamed porn theaters for Downtown’s decline while ignoring sprawl, so too did they imagine Martineztown’s problems as failures of community rather than failures of planning. In reality, the neighborhood bore the brunt of decisions made elsewhere: highways cut through its edges, arterials funneled traffic past its homes, and sector plans made promises that rarely materialized.

Martineztown persisted. Families stayed, churches held their ground, and neighbors kept arguing over what survival should look like and who gets to define it. That argument is not just historical. Today, neighborhood leaders like Angela Vigil and Loretta Naranjo-Lopez reject Downtown affiliation,28 echoing earlier fears of demolition and neglect. Others, then and now, have embraced connection, believing it brings resources and renewal. Identity, density, and investment have never split Martineztown into neat sides; they’ve produced overlapping, contested voices that still shape the neighborhood.

That endurance is what makes Martineztown such a crucial counterpoint to the council’s contempt for Downtown. While city leaders were treating the core as a containment zone for problems, Martineztown residents were asserting that they still had a future, even if they could not agree on what form it should take.

Martineztown’s walls and split votes reveal the deeper pattern of this era: decline was diagnosed as vice and disorder, not as the product of policy. Smut shops were blamed; zoning and road policy escaped scrutiny. Containment was celebrated Downtown while the periphery expanded unchecked. The consequences fell on places like Martineztown—concrete walls, narrowed options, and endless fights over whether to lean into the city or hold it at bay. That history complicates any tidy picture of a “decadent, expendable” core. It also echoes forward. Richard Martinez’s optimism that new housing could “improve the stature of Downtown living” and Cipriano Baca’s defense of generational continuity still bookend today’s debates: reinvestment as repair versus reinvestment as erasure. What hasn’t changed is a persistent provincialism about the core—treating Downtown as a special-interest zone rather than the civic heart. That refusal to build a strong, community-centered center doesn’t just hurt Martineztown; it weakens Albuquerque as a whole.

Martineztown remains caught in the middle—traumatized by road widenings, divided by walls, and too often forgotten in waves of planning. Its residents still weigh the risks of redevelopment against the need for dignity and survival, hoping the city will finally treat their neighborhood as more than expendable. Healing will not come from neglect. It will come from embracing the investment and care long denied, and from acknowledging Martineztown’s place not as an island walled off from the city, but as a vital part of it—a contributor to Albuquerque’s culture, resilience, and everyday life. The lesson is larger than Martineztown but instead touches our entire city. It is about what happens to a city that fails to protect and integrate its center, and how that failure radiates outward to shape the whole.

Richard Bell and the Taylor Ranch Uprising

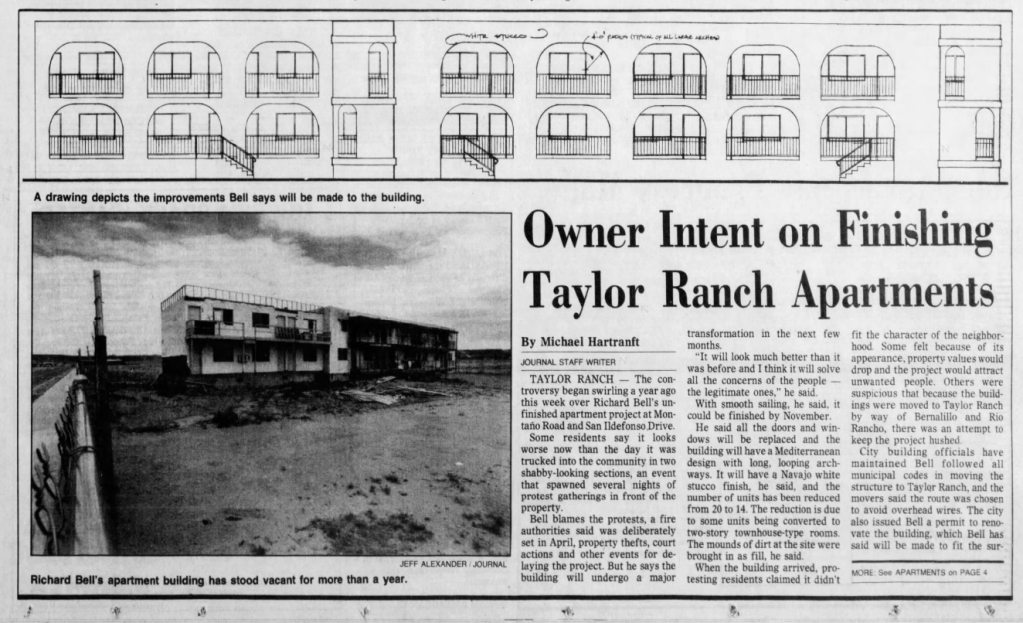

If you wanted to see how deeply Albuquerque’s sprawl hardened into exclusion, you could do worse than Taylor Ranch in 1989. There, on a bluff above the Rio Grande, residents rose up not against a freeway or a factory, but against apartments—prefabricated structures brought into their neighborhood by a Black developer named Richard Bell.

The episode which we can call the “Taylor Ranch Uprising,” and its drama—the protests, the fires, the threats, the political theater—was unlike anything else in the city at the time. Yet in hindsight, the uprising was less an aberration than a revelation. It showed how race, class, and zoning fused in Albuquerque’s suburbs, how the rhetoric of “codes” and “community standards” masked deeper fears, and how the city’s growth machine faltered when it tried to square suburban dreams with urban reality.

Richard Bell was not an outsider to Albuquerque’s growth story. He had developed housing across the metro, and by the late 1980s he saw opportunity on the Westside, where Taylor Ranch was booming with single-family homes. Bell was unusual in one crucial respect: he was Black, a rarity in the overwhelmingly white world of Albuquerque real estate development.

Bell’s plan was straightforward. He purchased six prefabricated apartment buildings from a site near Presbyterian Hospital and arranged for them to be moved into Taylor Ranch, a new subdivision marketed as family-friendly and orderly. The relocation was complicated, requiring a 40-mile journey through Bernalillo and Rio Rancho.30 By the time the structures arrived, neighbors were already suspicious. Bell promised improvements: Navajo white stucco, looping archways, townhome-style redesigns.31 He argued the apartments were legal, permitted, and consistent with Albuquerque’s need for housing. He saw no reason why renters should be excluded from Taylor Ranch.

“A Big Monster Out There”

Neighbors disagreed. From the moment the first building appeared, protests erupted. Residents crowded the streets, blocked trucks, and shouted down work crews. Fires broke out in the half-finished structures.32 Rumors spread that the apartments were dangerous, cheap, and substandard.

One neighbor, quoted in the Journal, captured the mood: “I open my back door, there’s a big monster out there.”33

The language is revealing. The “monster” was not the building itself. What neighbors feared was less the building itself than what it symbolized: density, renters, change and of a more diverse Taylor Ranch. Residents worried openly about “the types of tenants it might attract.” Substandard became the catchword. But substandard, in this context, did not mean structurally unsound. It meant socially suspect.

Bell accused opponents of racial bias, and he was not alone. Observers noted how quickly the fight escalated beyond design quibbles into character attacks and arson. As a Black developer bringing renters into a homogenous suburb, Bell embodied anxieties that were rarely voiced directly. Instead, neighbors invoked “codes,” “property values,” and “community character.”

The City’s Dance

City Hall scrambled. Councilors Pete Dinelli and Pat Baca introduced legislation to condemn the apartments as “ruined, damaged and dilapidated,” even though they were new buildings to the area trucked across town and which had ambitious plans in place to renovate them.35 Mayor Ken Schultz considered buying out Bell. Martin Chavez, then a young attorney with political ambitions, suggested the state purchase the site for public housing or schools.36 Bell tried to stand firm. He insisted the project was legal, that opposition was rooted in prejudice, and that renters deserved housing in Taylor Ranch. But the harassment wore him down. Don Newton, president of the Taylor Ranch Neighborhood Association (TRNA), later recalled a phone call in which Bell’s voice was “full of fear,” convinced his life was in danger.37

Within months, Bell gave up. “I’m just sick of it. I’ve got other things I need to do with my life. It’s cost me too much money.”38 He left Albuquerque, abandoning the project.

The Softball Field Parable

In the documentary Neighborhoods at a Crossroads, TRNA leaders insisted their opposition was not about animosity. In speaking about why the neighborhood has blocked or protested so many proposal, TRNA secretary Terri Spiak stated: “We take the responsibility of protecting the neighborhood very seriously. The things we do, we don’t do them out of a personal agenda, at all, because it is all grounded in the existing code and regulations or an effort to change them.”39

As Spiak spoke, the film celebrated the blocking of not only Bell’s development but also numerous other apartment proposals and even a neighborhood softball field. The field was deemed too noisy, too disruptive, too dense with activity. The pattern was clear: the fight was not really about legality or building quality. It was about protecting a suburban ideal that equated stability with uniformity. In that world, even a recreational field was seen as an intrusion. Apartments, which bring renters, diversity, and change, were unthinkable.

Zoning as Exclusion

The Taylor Ranch Uprising centered on Richard Bell, but its roots lay in the zoning system that made apartments anomalies in the first place. Single-family zoning had carved most of Albuquerque into neighborhoods where apartments were either prohibited or heavily restricted. That meant multifamily housing had to squeeze into the few parcels where it was legal. Bell’s apartments were legal, but they were also conspicuous—trucked in, surrounded by single-family homes, and visually marked as different. This is the structural contradiction of sprawl: the city needed density to house its growing population, but its zoning ensured density would always appear out of place. The system produced conflict by design.

National Parallels

Albuquerque was not unique. Across the United States, suburbs resisted apartments in the 1970s and 1980s. In St. Louis County, homeowners fought low-income housing projects. In Orange County, California, residents rallied against “crackerbox apartments.” In New Jersey, exclusionary zoning prompted the famous Mount Laurel court cases.40

As Andrew H. Whittemore observes in Exclusionary Zoning: Origins, Open Suburbs, and Contemporary Debates, early zoning was designed to “sort out cities by housing type,” advancing the idea of a socially stratified city as a desirable outcome.41 That logic has never disappeared, even when buried under language about “character” or “property values.” Katherine Levine Einstein, David M. Glick, and Maxwell Palmer show in Neighborhood Defenders how contemporary residents weaponize those very terms to block multifamily housing through public hearings and procedural delay.42 Taken together, these accounts reveal how exclusionary zoning’s origins and its present-day defenses share the same underlying project: preserving racial and class homogeneity under the neutral cover of planning. The Taylor Ranch opposition to an apartment complex in the 1970s exemplifies this continuity, as residents recast fears of integration and decline into the ostensibly race-neutral language of protecting neighborhood character.

Municipalities used police powers to restrict residential density and building forms in ways that systematically excluded less affluent (and frequently non-white) households from neighborhoods that were otherwise made attractive by public services and infrastructure. Zoning thus became a subtler successor to explicit racial covenants.

Taylor Ranch fit this pattern perfectly. Bell’s apartments threatened not just property values, but the racial and class homogeneity of the Westside.

The Human Cost

For Bell, the cost was financial and personal. He lost money, time, and ultimately his place in Albuquerque’s development world. For renters, the cost was opportunity denied. The Westside remained overwhelmingly single-family, leaving apartments clustered in older, less affluent areas.

For Taylor Ranch, the cost was subtler. The uprising hardened the neighborhood’s identity as anti-apartment, anti-density, anti-change, and perhaps the heart of Albuquerque’s NIMBY contingent. It became a template for future fights, from parks to roads to bridges. TRNA, forged in the Bell battle, became one of the city’s most influential and combative neighborhood associations, and its most vociferous spokespeople often also oscillated to the Westside Coalition of Neighborhood Associations – perhaps the largest NIMBY organization in New Mexico.

A Template for the Future

The Taylor Ranch Uprising did more than stop one project. It set the tone for decades of suburban politics in Albuquerque:

- Fear coded as codes. Residents claimed to follow the law, but their objections revealed deeper anxieties.

- Exclusion cloaked in civility. Density was opposed not with slurs, but with “quality of life” arguments.

- Neighborhood power institutionalized. TRNA grew into a formidable force, shaping city policy well beyond its borders.

Bell was right. The apartments were legal, needed, and consistent with growth. But legality, need, and consistency meant little in the face of organized exclusion, racism, classism, and fear.

Monsters and Memories

When one neighbor described Bell’s apartments as “a big monster out there,” she meant it as a complaint. But the phrase lingers as an unintended truth. Neighbors called the prefab shells “monsters.” Maybe they truly believed that. What truly loomed was the zoning code that made any apartment feel out of place. The code entrenched exclusion and encouraged a neighborhood to police its borders. We were, and remain, a city that chose appeasement over equity, and this led to a protest environment that encouraged racist vandalism and destruction.

Bell left. The apartments vanished. Taylor Ranch remained. But the uprising left a scar that shaped Albuquerque’s growth for decades to come and shows that deep, violent racism that still permeates the culture of our governance and planning—from neighborhood associations and coalitions to city leaders.

Having stopped apartments as ‘disorder,’ Taylor Ranch then pivoted to demand the infrastructure sprawl requires.

The Montaño Bridge: A Cottonwood Falls

From Uprising to Demand

The Taylor Ranch Uprising of 1989 had proven one thing: the neighborhood could mobilize. What began as a fight against Richard Bell’s apartments hardened into a worldview, one where density was framed as disorder and renters as interlopers. But Taylor Ranch was not anti-development in any pure sense. Like many suburban communities, it resisted growth until growth served its interests.

By the early 1990s, Taylor Ranch had swelled with single-family homes. Commuters funneled east each morning, idling on the few bridges that spanned the Rio Grande: Central, I-40, and eventually Paseo del Norte (El Pueblo Bridge in early planning documents). The drive to Downtown could stretch an hour on a bad day. For residents, the bottleneck was intolerable. What they wanted now was not preservation, but connection.

And so the same neighborhood that fought to keep apartments out turned to demand a bridge in.

The TRNA as an Army

The Taylor Ranch Neighborhood Association (TRNA), emboldened by its victory over Bell, now trained its organizing power on the Montaño Bridge. What had begun as talk at board meetings became a full-fledged campaign.

Diana Shea, TRNA president, recalled one pivotal moment in the early 1990s: Martin Chávez, then an ambitious attorney, stormed into a TRNA meeting with papers in hand. “Here’s how we’re going to get the bridge,” he told them. To Shea, the message was clear: political power would align with neighborhood demand.44

For residents like Peggy Minich, the issue was constant: “The noise about the Montaño Bridge started way before it was completed in ’97. Access back and forth was a huge issue because most people then worked on the other side of the river.”45

Mike Creusere, another TRNA president, put it more bluntly: “It was pretty obvious that bridges were going to be needed and that was going to be a battle because the North Valley didn’t want the bridges and they fought us tooth and nail and we fought them tooth and nail. It was a long struggle—they even tried to get legislation to block it.”46

For Taylor Ranch, the bridge was justice, overdue and non-negotiable. For the North Valley, it was an existential threat.

The North Valley’s Stand

To understand the opposition, you had to understand the place. The North Valley was one of Albuquerque’s oldest cultural landscapes: a patchwork of acequias, cottonwoods, horse pastures, and small farms. It was rural life inside the city, and residents treasured it.

The idea of a four-lane bridge cutting across Montaño Road threatened that identity. Traffic would roar through narrow lanes, bringing noise, pollution, and a stream of suburban commuters. To North Valley residents, the bridge was not mobility but an invasion.

John O’Connor, mayor of Los Ranchos, said it plainly: “We don’t want a 7-Eleven on each corner. We like the smell of horses and fertilizer and the sounds of chickens and roosters.”47

Opponents rallied around environmental arguments. Ecologists testified that the bosque was one of the richest riparian corridors in the Southwest, home to migratory birds, wetlands, and old-growth cottonwoods.48 Cutting a road through it would fragment habitat, dry out channels, and scar one of Albuquerque’s few natural treasures.

For many in the North Valley, protecting the bosque was synonymous with protecting their way of life. For TRNA, it sounded like obstruction cloaked in idealism. Creusere dismissed it outright: “They use all kinds of tactics, including trying to talk about the natural ecosystem, which I didn’t buy… It was a nice valley, I have to admit, but I wasn’t buying the argument.”49

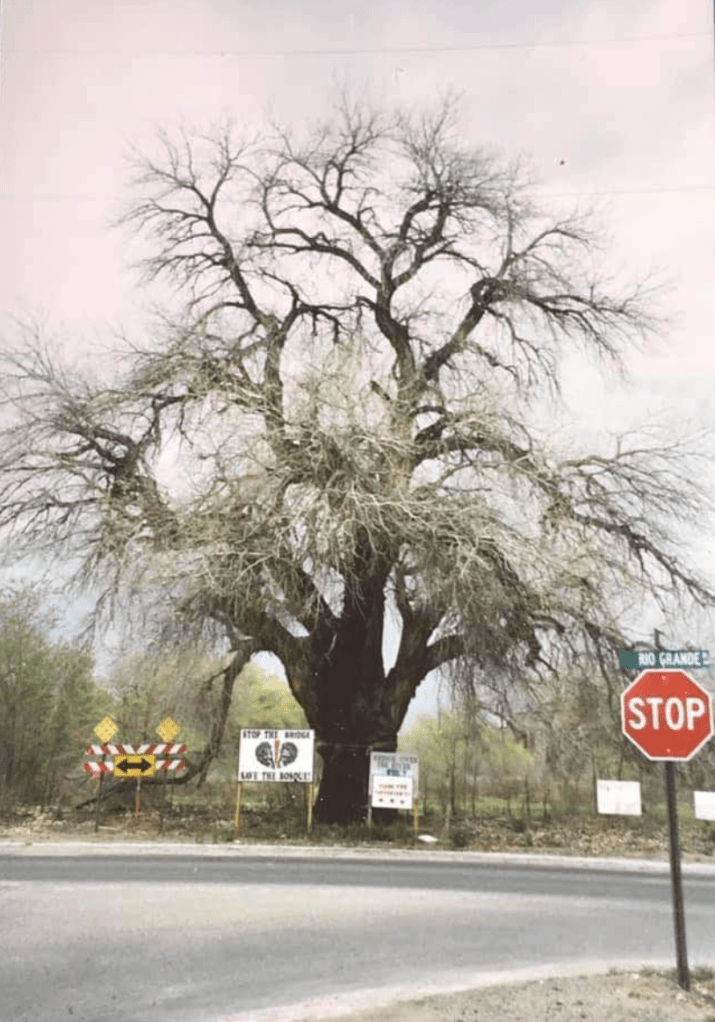

The Cottonwood Martyr

At the heart of the fight stood a tree.

A forty-foot cottonwood rooted in the bosque along the bridge’s proposed path became the rallying point for opponents. They plastered its bark with signs: “Bridge Over the River Why?” Protesters chained themselves to its trunk, seeing in it the embodiment of their cause: nature versus pavement, heritage versus expansion, stillness versus sprawl.

When the bulldozers came, the cottonwood’s fate was sealed. Finally, heavy equipment dragged its carcass away. The High Country News delivered the epitaph in one line: “Traffic flow 1, trees 0.” In the pages of the Tribune, Burqueños mourned its loss.50

The North Valley mourned the tree; Taylor Ranch celebrated the bridge; Albuquerque was left with a scar that still lingers, both physical and social, and one that has become emblematic of current fights and tensions.

The Forgotten Tree?

Not everyone remembered it as sacred. Yolanda Hebert, a Taylor Ranch resident, recalled it almost as a curiosity: “The main thing I remember about Montaño Road being built was there was a big old tree that people didn’t want cut down. People were protesting because they didn’t want the tree cut. I thought it was a good idea because there were more ways to get to the Heights. So I was for it, and I’m glad it happened. Nobody now probably remembers that big tree.”51

She was half right. Many forgot. But for those who grew up in Albuquerque in the 1980s and 1990s, the tree was unforgettable. It was where some of us learned the language of environmentalism; it was where others became urbanists, or now, YIMBYs, seeing how preservation talk could be used to block a bridge even as cul-de-sacs marched across the desert. Over time, many of us became both, and allies: recognizing that single-family sprawl was the common harm, that bosque-versus-bridge was a false choice, and that the hypocrisy and myopia on display were not sustainable. The real work was changing the rules that outlawed infill and mixed use, so environment and mobility, affordability and belonging, could point in the same direction.

The cottonwood’s fall became a generational education in selective morality. They cut the tree. Kids in the Valley still talk about it. For them, it wasn’t a lesson in morality so much as proof the rules bent for some and not for others and that localism is a trap that is far too appealing and easy to fall into and the results are almost always bad.

Philadelphia, New York, and the Pace of Change

Dan Curtiss, another TRNA president, often compared Albuquerque to older cities: “In Philadelphia and New York there’s a bridge every two blocks, and here it took decades to get one. That shows you how slow things go when people get entrenched in what they’ve got.”52

His observation revealed Albuquerque’s contradictions. In cities with dense cores, bridges were unremarkable infrastructure. In Albuquerque, each crossing was existential, a referendum on who belonged and what landscapes mattered. They admired the crossings but not the city the crossings serve. In the same breath that demanded East Coast throughput, they rejected East Coast form: attached housing, mixed-use blocks, apartments near jobs. It’s a one-way borrowing: infrastructure without urbanism, growth without diversity.

What people fought over wasn’t commute times so much as whether their neighborhood would be suburban or rural.

Selective Environmentalism

The environmental arguments around Montaño mattered, but they were also selective. The bosque was treated as sacred. The desert, by contrast, was expendable. Taylor Ranch itself sat atop land once covered with sagebrush, arroyos, and fragile soils. Its cul-de-sacs and lawns had already trampled ecosystems.

Yet few residents mourned that loss. Environmentalism became urgent only when it preserved a cherished landscape, not when it confronted the consequences of sprawl. The cottonwood was mourned. The sagebrush was forgotten.

This hypocrisy ran in both directions. TRNA residents dismissed bosque protections as “phony,” yet demanded a bridge to shorten commutes made necessary by sprawl. North Valley preservationists invoked ecology against the bridge, but rarely acknowledged that blocking infrastructure only pushed growth further outward, onto farmland and mesa alike.

The Zoning Trap

The refrain from Taylor Ranch—“We couldn’t afford to buy on the east side”—was both true and incomplete.53 Eastside neighborhoods, with their tree-lined streets and historic housing stock, were increasingly expensive. For middle-class families, the Westside offered cheaper land and new homes.

But the affordability came at a cost, one created by the very structure of Albuquerque’s zoning code. By locking most of the city into single-family zoning, Albuquerque outlawed incremental infill in its core. Density was blocked in older neighborhoods. Apartments were met with fury and small-scale evolution was impossible.

The result was forced sprawl. Families priced out of the Eastside had little choice but to leapfrog westward. But once there, they found themselves trapped: dependent on bridges, dependent on cars, and pitted against their North Valley neighbors in battles that were less about choice than about inevitability.

The zoning trap didn’t just ensnare Taylor Ranch. It also shaped the North Valley, where environmentalism and affinity for a rural aesthetic became the banner for bridge opposition. By the 1990s, much of the valley had already begun its transformation into a higher-wealth enclave, where preserving “character” often meant shutting out new housing or incremental change. That exclusivity came at a cost: by blocking infill and density in the core, North Valley residents effectively pushed growth to the Westside mesas, paving sage and desert, lengthening commutes, and forcing the very bridges they opposed. In this way, the zoning regime harmed both sides — trapping Taylor Ranch in sprawl and commute dependence, while undermining the North Valley’s own ecological values.

The Montaño Bridge fight was not just about one crossing. It was the symptom of a system that outlawed evolution, strangled infill, and left growth to spill outward in the most destructive ways.

Two Sides, Unequal Stakes

Diana Shea, TRNA president, later reflected: “There were reasons not to build that Montaño Bridge, but they were overridden by the reasons we had for building the bridge. There’s always two sides to every issue.”54

But the sides were not equal. For the North Valley, the bridge meant disruption, noise, and the erosion of rural identity. For the Westside, it meant some relief from traffic, access to jobs, and rising property values. For the city, it meant accommodating growth it had already permitted.

Each side fought for its own survival. But both were trapped by the same system: a city built on exclusionary zoning, dependent on sprawl and busy highways, and incapable of reconciling growth with equity.

The Bridge Opens

In 1997, after decades of lawsuits, protests, and bitter public hearings, the Montaño Bridge opened. Cars streamed across, cutting commute times. For Taylor Ranch, it was a triumph. For the North Valley, it was a wound. For the bosque, it was another scar.

The cottonwoods were gone. The tree was gone. The traffic was here to stay.

Legacies of Montaño

The Montaño Bridge left legacies that extend well beyond its asphalt:

- Environmentalism as Selective

The fight revealed how environmental values could be sincere and hypocritical at once. The bosque mattered, but so did the sagebrush. Protecting one while paving over the other was not stewardship. It was convenience. - Zoning as a Trap

The refrain about affordability revealed the deeper problem: a city that outlawed density in its core, forcing families outward and guaranteeing sprawl. Single-family zoning made the bridge fight inevitable. - Neighborhoods Versus Neighborhoods

Albuquerque’s planning failures left communities to battle one another. Taylor Ranch versus the North Valley was not just a clash of interests. It was the predictable outcome of a system that made conflict the price of growth. - The Cottonwood as Symbol

Yolanda Hebert was right that many forgot the tree. But for those who remember, it remains a symbol—not just of loss, but of awakening. It showed how values were deployed selectively, how noble causes could mask exclusion, and how the city failed to confront the structures behind the fight.

The Tree and the System

The Montaño Bridge fight wasn’t really about traffic counts. It was about who got to call the shots — and who was left carrying the costs. It showed how the system causes neighborhoods to fight symptoms rather than causes: environmentalism applied selectively, affordability pushed ever outward by single-family zoning, and the city’s heart left stagnant. It also previewed a fierce localism that still infects Albuquerque’s politics and intentionally positions neighbors against each other while ignoring regional impacts.

When the cottonwood fell, it was mourned by some, forgotten by others, but its lesson endures. It taught us that the real battle was not between the Westside and the North Valley, but between a city’s myths of stability and the realities of its growth.

The cottonwood fell, commuters cut ten minutes, and the bridge stayed. We built a city where every crossing is a referendum because we outlawed change where people already live.

The Coors Conundrum

A Corridor in Crisis

By the mid-1980s, the Westside had grown so fast that planners decided it needed a coherent vision. The result was the 1984 Coors Corridor Plan, a dense set of guidelines and maps meant to regulate development along one of Albuquerque’s busiest arteries.

From the start, the Coors Corridor Plan mistook scenery for sustainability and localism for planning, writing ambiguity into law and conflict into the corridor.

The plan promised to balance growth with environmental protection. Its centerpiece was a “view protection” policy designed to preserve sightlines of the Sandias and the bosque. In practice, it collapsed under its own contradictions. Planners themselves admitted the plan was “difficult to understand and ambiguous.” No one could agree whether its guidelines were mandatory or optional.

By 1988, it was clear the “view protections” were unworkable. But abandoning them proved impossible.55 Vitriolic opposition from increasingly powerful neighborhood associations and coalitions ensured that the policy lingered in the code, burdensome yet immovable. Instead of offering clarity, the Coors Plan institutionalized confusion; its very vagueness became a weapon residents could wield to oppose development.

The corridor became a battleground where nothing was clear, everything was contested, and the real needs of the city were subordinated to endless disputes over aesthetics and process.

False Environmentalism

The Coors Plan epitomized a kind of false environmentalism that took hold in Albuquerque in the late twentieth century. It claimed to protect views of the Sandias and the bosque, but it did little to address the underlying environmental consequences of sprawl: paving farmland and desert, extending infrastructure, and forcing longer commutes. “View protection” became a convenient shield for blocking growth, while real environmental issues (air quality, water use, ecosystem fragmentation) were ignored.

This pattern echoed the Montaño Bridge fight. Just as proponents claimed the mantle of affordability while disregarding the ecological, social, and ironically, the affordability costs of sprawl, so too did the Coors Plan elevate scenery over sustainability. The city congratulated itself for protecting a distant mountain view even as it consumed the desert underfoot.

Localism Institutionalized

What made the Coors Plan truly significant was not its content but its structure. It was a sector plan, a specialized code layered atop the city’s zoning ordinance. Rather than a clear, citywide vision, it created a hyper-local regulatory regime.

That structure encouraged neighborhood parochialism. Instead of thinking about the Westside’s role in the region and its need for housing, infrastructure, and integration into the city’s whole, the Coors Plan locked the debate into endless fights about corridor character, traffic counts, and setbacks.

This was the logic of sector planning: carve the city into fragments, let each fragment defend itself, and hope coherence emerged. It never did. By the 2010s, Albuquerque had more than 400 separate zones and sector plans, a patchwork that paralyzed planning and emboldened NIMBY opposition at every turn. Divided into five separate documents, our city could even claim to have well over 1,200 zones when all five documents were considered together—among the most complicated land use codes in the country.

A Blueprint for Conflict

The Coors Plan did more than confuse. It provided a toxic blueprint for how Albuquerque’s contemporary NIMBYism would operate. By framing development as a threat to aesthetics and “character,” it gave residents a ready-made vocabulary to oppose change. By enshrining ambiguity, it guaranteed fights: neighbors versus developers, neighborhoods versus the city, the Westside versus the valley.

It was no accident that the Taylor Ranch apartment uprising and the Montaño Bridge protests flared in this same era. The city had written conflict into law. When residents torched Bell’s apartments or chained themselves to a cottonwood, they were following the logic of a planning regime that made every project a zero-sum battle.

The ambiguity didn’t just confuse but it empowered. Neighborhood groups seized on the vagueness to challenge projects they disliked, framing them as inconsistent with the Coors Plan.

When a proposed shopping center in Paradise Hills came forward in 1987, the Coalition of Westside Neighborhood Associations filed an appeal, claiming it violated the Coors Plan. Their objection wasn’t to the mall itself, but to details: a median cut on Coors, extra signage, the specter of traffic and air pollution.56 57

“If the Coors Corridor was worth protecting, and many citizens worked years with developers, city staff, and experts to develop the Coors Corridor Plan … it seems that a constant ‘picking’ at the plan will deteriorate it to the point of ‘worthlessness,’” coalition chair W.D. “Bill” Brannin warned.58

In effect, the plan became a neighborhood cudgel: an ambiguous set of rules that could be interpreted broadly enough to oppose almost anything, from a curb cut to a big-box store.

The code preserved distant mountain views while ignoring what happened on the ground underfoot (or really, undertire). The windows were in the code; the walls were in the neighborhoods.

Midcentury Missteps, Reinforced

In this way, the Coors Plan was, and in many ways remains, the continuation of midcentury missteps. Albuquerque had already cut itself apart with highways and road widenings. Instead of pivoting toward holistic growth, the city doubled down on fragmentation. Each neighborhood became its own fiefdom, empowered to say no but rarely to imagine a bigger yes.

This was the moment when Albuquerque’s contemporary NIMBYism took root. The Bell apartments were cast as monsters, the Montaño Bridge as an invasion, and the Coors Plan as the rulebook for obstruction. Far from healing the city’s divisions, sector plans deepened them. They gave localism the force of law and made comprehensive, citywide planning impossible.

The Conundrum’s Legacy

Looking back, the Coors Corridor Plan was less about Coors Boulevard than about the city’s planning philosophy. The plan showed Albuquerque confusing localism with democracy, and scenery with sustainability, and how it wrote ambiguity into policy. Everyone nodded along to the neighborhood’s vetoes, but nobody could explain how it worked for everyone. The problems the plan was meant to solve (traffic congestion, disordered growth, the need for housing) were made worse by its very structure. By blocking density and promoting piecemeal regulation, it pushed development further outward, worsened congestion, and preserved exclusion under the guise of environmentalism.

The Coors Corridor Plan gives us a clear glimpse into the broader system it inhabited: the 1975 zoning code, steadily swollen with amendments and sector plans until it became a patchwork of more than 400 unique zones. Even though the Integrated Development Ordinance, or IDO, Albuquerque’s “new” zoning code, was meant to sweep that clutter away in 2017, pieces of the Coors logic survive. Character Protection Overlays, or CPOs, written into the IDO as concessions to neighborhood demands, are vestiges of sector planning, carrying forward many of the same unworkable ambiguities and parochial instincts that made the Coors Plan infamous. In that sense, the Coors Conundrum is not just a historical episode — it is a live problem embedded in the city’s present code. It pitches neighborhoods against each other, attempts to weigh localist concerns against regional needs, and prioritizes some groups over others. In many states, including California, overlays like this are being preempted as smokescreens that allow cities to avoid their commitments to housing and commerce. The continued existence of the Coors “View Protection Overlay” points to this need in our state, too.

Scholars have shown how this language works in practice. Katherine Einstein & colleagues detail how invocations of ‘neighborhood character’ turn public hearings into reliable tools of exclusion. Yoni Appelbaum, writing about why so much of American governance feels ‘stuck,’ shows how preservation-style veto points, from historic districts here, to ‘view protection’ there, arm small coalitions with the power to freeze change.59 These neighborhood-level choices produce region-wide constraints on housing supply, mobility, equity, and opportunity. Albuquerque’s CPOs fit that pattern: procedurally neutral on paper, functionally selective in whose interests they protect.

The Coors Plan did not just foreshadow the chaos of 400 (or 1,200, depending on how we wish to count them) zones by the 2010s. It planted the seeds. It showed how the city, faced with the challenge of growth, chose a toxic blueprint: one that empowered obstruction, paralyzed vision, and left Albuquerque fighting itself instead of planning for its future. We still live in this broken system that privileges some over others and it rears its head at nearly every council meeting.

Dreams of Downtown Revival

By the late 1970s, Albuquerque had already run a generation of experiments in urban renewal, most of them ending in scars: wide one-way streets, half-empty parking lots, and demolished landmarks. Yet even as the city sprawled outward, Downtown refused to disappear entirely. The question was never whether Downtown existed, but what purpose it served.

For some leaders, the answer was blunt: Downtown was expendable, a holding zone for the uses no one else wanted. In the 1980s, that logic was made explicit in debates about adult theaters and smut shops. Councilors like Pete Dinelli argued that if such businesses had to operate, they belonged Downtown; an approach that revealed both a contempt for the core and an unwillingness to imagine it as anything more than containment.

Preservationists refused to concede and rallied around survivors like the Sunshine Theater, which had escaped the wrecking ball more than once. Planners floated visions of festival marketplaces and retail pavilions, ill-conceived as they often were, because they still believed Downtown could be reinvented. Even the most desperate schemes acknowledged something crucial: the heart of the city was too important to simply abandon.

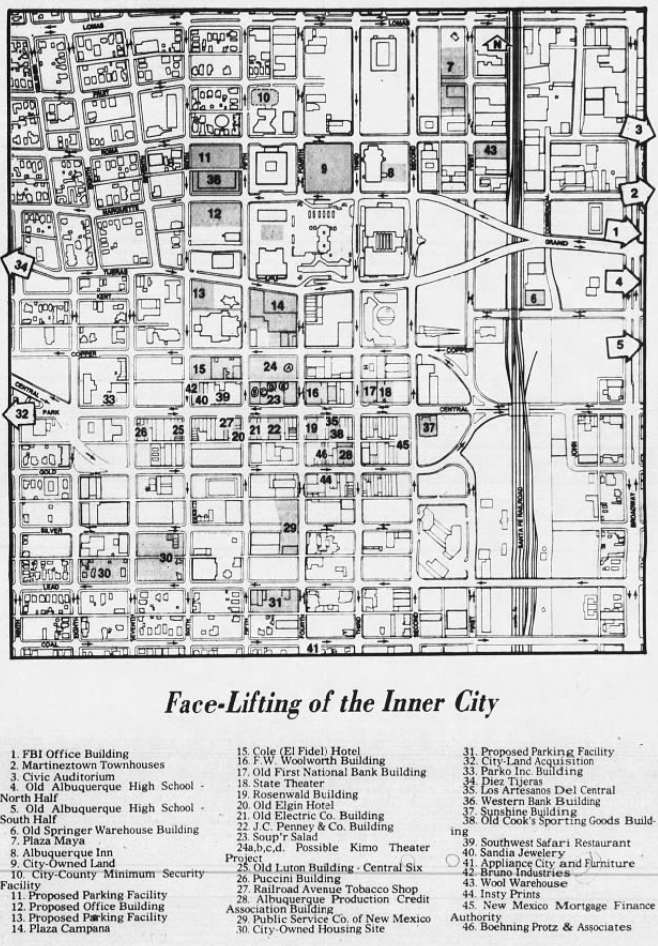

That tension between containment and reinvestment shaped the next two decades of Downtown planning. The Festival Marketplace proposal, the flirtation with façadism, Jim Baca’s pivot toward constructive projects like the Theater Block and Alvarado Transportation Center, the skyline-shifting BetaWest towers, and eventually the Downtown 2010 Plan all grew from this divide. Was Downtown to be written off as a dumping ground for vice, or reclaimed as the civic and cultural anchor of Albuquerque?

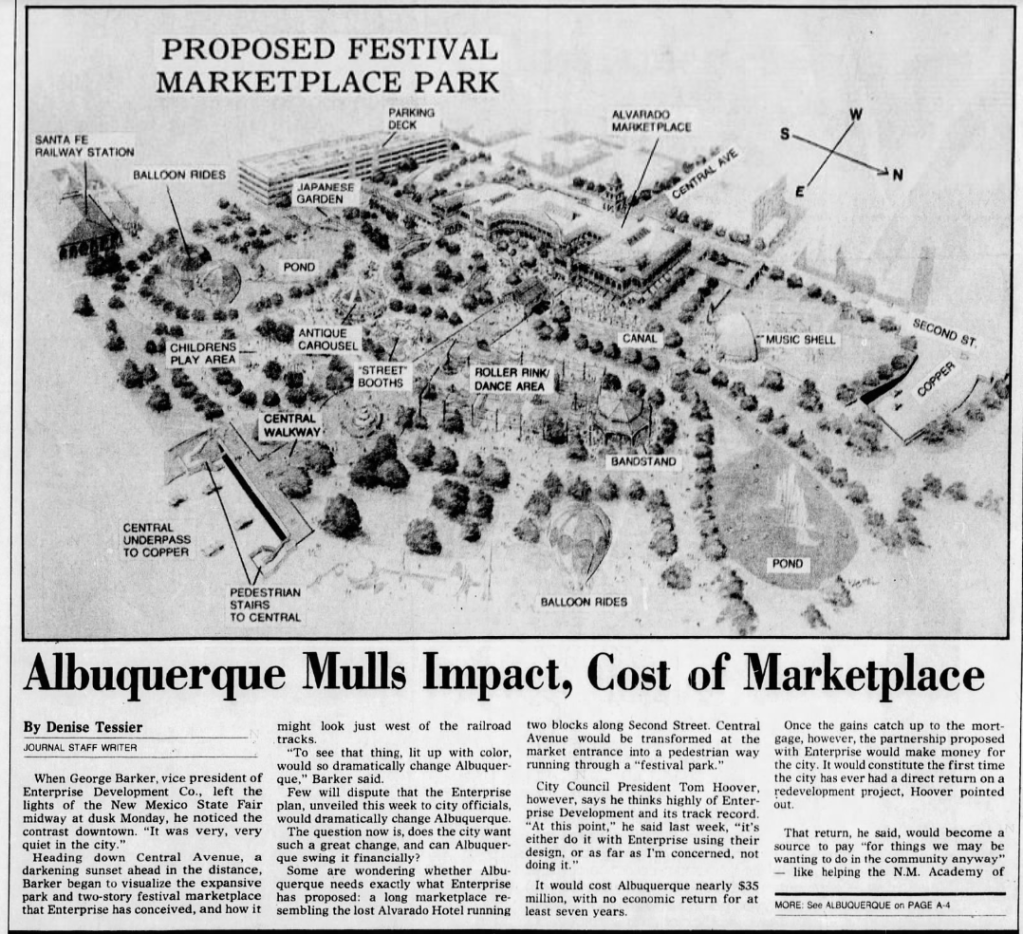

Festival Market: Downtown as Spectacle

If the 1970s had left Downtown gutted by renewal and abandonment, the 1980s brought a different kind of ambition: reinvention through spectacle. Like dozens of cities across the country, Albuquerque flirted with the fad of the festival marketplace—retail-and-entertainment complexes inspired by Baltimore’s Harborplace or Boston’s Faneuil Hall. The idea was simple: if traditional downtown shopping was dead, then turn the corpse into a stage set, a place where tourists and suburbanites might come for carefully packaged experiences.

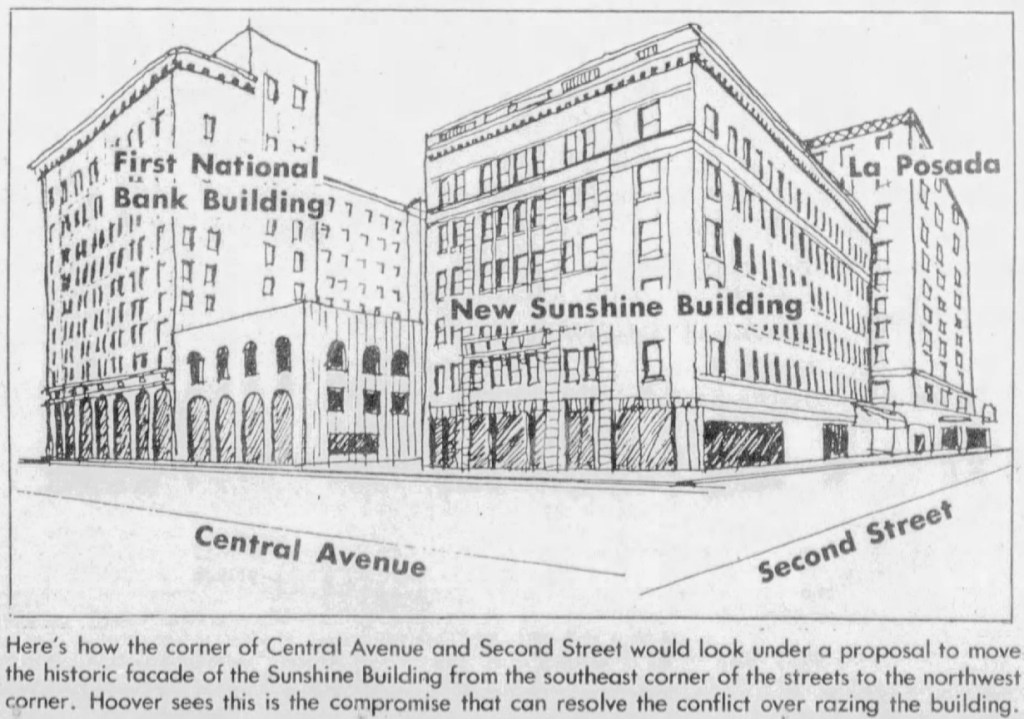

In Albuquerque, that meant a direct threat to one of Downtown’s last survivors: the Sunshine Theater. Developers proposed demolishing the Sunshine outright to make way for a retail pavilion, with one compromise so absurd it still lingers in memory: tear the building down, but reconstruct its façade across the street,60 an architectural fig leaf to hide the erasure. It was “preservation” drained of meaning—a shell without a soul, history recast as stagecraft.

The plan did not stop at the Sunshine. Portions of Central Avenue itself were to be closed, not as pedestrian malls but as erasures, streets wiped from the grid and replaced with landscaped plazas and a proposed “Market Festival Park.” In eastern Downtown, blocks of Central were drawn as blank space on planning diagrams, a parkland fantasy in which the messy work of actual commerce and life would be replaced by controlled leisure. The same logic that had justified demolishing the Alvarado Hotel in 1970 was back: the past wasn’t to be preserved but to be re-created in sanitized form.

There was even talk of constructing a facsimile of the Alvarado Hotel, paying homage to what had been lost without grappling with why it was torn down in the first place. It was nostalgia rendered in plaster and drywall, a substitute for reckoning. The message was clear: Downtown could be reborn, but only as imitation, never as itself.

These proposals echoed earlier efforts to cut and widen Central, to bend the street grid to fit a singular vision. Once again, the lived-in mess of Downtown from the cheap storefronts, the apartments, and the small businesses, was treated as expendable. In its place, planners envisioned controlled spaces of consumption, disconnected from the neighborhoods around them.

What’s striking in retrospect is not only how far these proposals went, but how close they came. That the Sunshine still stands today is almost accidental, the result of preservationists and inertia thwarting what might otherwise have been a very different landscape. Had the Festival Market been realized, Downtown might have lost one of its most enduring anchors, trading an authentic survivor for an ersatz homage.

And yet, embedded in even these flawed proposals was a paradoxical acknowledgement: Downtown still mattered. If it were truly expendable, there would have been no reason to stage such elaborate reinventions. The Festival Market may have been misguided, but it was also a confession that Albuquerque could not quite let its center go.

The Skyline Returns: BetaWest and Albuquerque Plaza

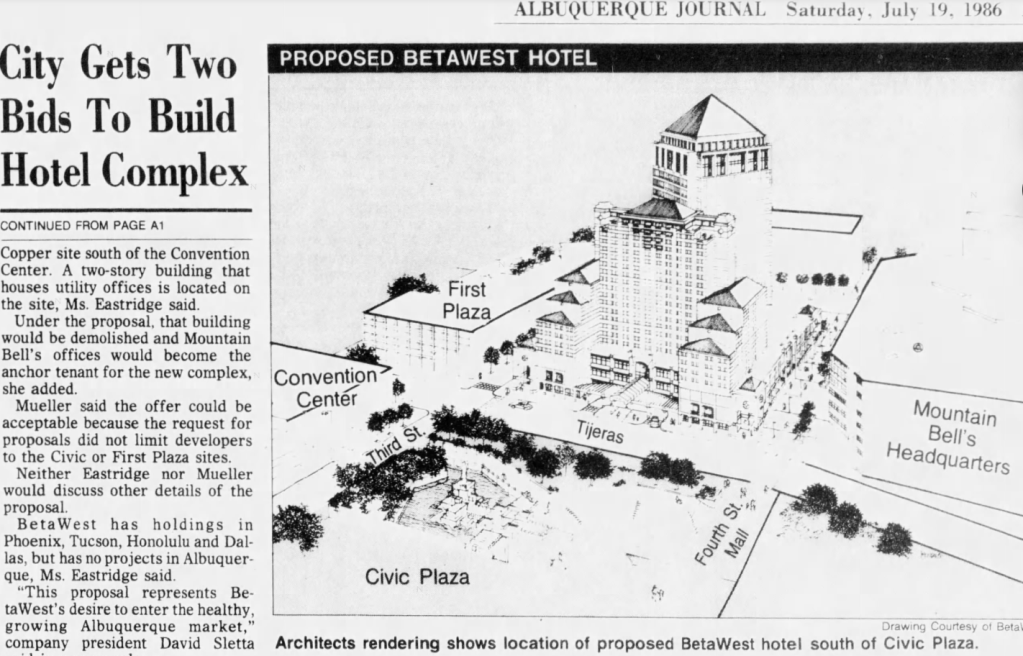

Even as Baca’s administration promoted repair through culture and transit, another force was reshaping Downtown: the business of conventions. By the mid-1980s, consultants were blunt. Albuquerque’s convention center was hobbled not by its size but by its context: the lack of first-class hotel rooms nearby.63 Without new lodging, the city was potentially losing conventions, and revenue, to nearby cities.64

This became the wedge for Downtown’s largest private investment in decades. In 1986, BetaWest Properties, a Denver-based developer, proposed a bold project: an 18-story office/hotel/retail complex on Civic Plaza, anchored by a Hyatt Regency hotel. Public subsidies and UDAG grants were quickly lined up to make the numbers work. Local skeptics worried about costs and whether conventions alone could sustain such scale. But the political momentum was irresistible and the City provided $2,000,000 to get the project across the finish line.65

Construction began in 1988, and by 1990 the twin towers of Albuquerque Plaza and the Hyatt Regency rose over the city, capped with their signature pink pyramids. At 22 stories, Albuquerque Plaza became, and remains, the tallest building in New Mexico.

The symbolism mattered as much as the steel. In Part Two of this history, the First National Bank Building at San Mateo and Central had stood as the marker of the city’s shift away from Downtown — a skyscraper rising far out on the fringe, declaring the future lay in the suburbs. The BetaWest towers represented a modest but meaningful reversal. After decades of sprawl and flight, Albuquerque’s tallest buildings were once again in the historic core.

This was not a wholesale return of investment; Uptown67 and the Westside68 continued to boom, and Downtown remained fragile but the pink pyramids were proof that the center still had gravitational pull. They became postcards, skylines, shorthand for Albuquerque itself. However, the towers rose not from a housing boom or an organic surge of businesses choosing Downtown, but from a carefully engineered public-private deal tied to the convention economy. Their lobby was oriented toward visitors, not residents; their retail struggled to fill. The project made Downtown look like a city again, but it did not, by itself, make it function like one.

Still, the towers marked a turning point. They demonstrated that large-scale investment in the core was possible, even in a city addicted to sprawl. They signaled that Downtown could be more than a holding zone, more than façadism, more than nostalgia. And they gave Albuquerque a skyline that, however contested, re-centered the city’s visual identity on its historic core.

Jim Baca and the Turn Toward Repair

By the early 1990s, the Festival Market dream had collapsed under its own weight. Financing never materialized, and the notion of demolishing the Sunshine to rebuild its façade across the street was so transparently absurd that it could not survive serious scrutiny. But the deeper shift came in the city’s politics. When Jim Baca took office as mayor, he brought with him a very different vision of Downtown.

Where the Festival Market saw Downtown as a stage set, Baca insisted on treating it as a neighborhood; one that could once again be lived in, walked through, and anchored by real institutions. His administration promoted a series of projects that signaled a pivot from demolition to repair:

- The Theater Block redevelopment,69 which aimed to concentrate arts and cultural activity near the Sunshine and KiMo, rather than raze what was left. Instead of façadism, this was about reactivating surviving landmarks.

- The Alvarado Transportation Center, a deliberate attempt to atone for the demolition of the Alvarado Hotel. By reconstructing a station on the same site, Baca framed the project as a kind of civic penance — a way to bring back what had been callously destroyed in the name of progress. Even though Greyhound and Amtrak resisted fully integrating into the hub at first, the symbolism mattered: Albuquerque was, at last, trying to rebuild what it had lost.70

- Housing initiatives, including the “Zona de Colores”71 and Villa San Felipe apartments, which marked one of the first serious efforts in decades to bring residents back Downtown. For the first time since suburban flight hollowed out the core, the city was acknowledging that office towers and parking lots could not alone sustain a center.

These moves were far from perfect. The Alvarado project was hamstrung by federal agencies’ reluctance to participate. Villa San Felipe was criticized for its expense and delays.72 73 And the Theater Block was only a partial success, more a cluster of projects than a cohesive cultural district.

But compared to the bulldozer mentality of the 1970s or the theme-park fantasies of the 1980s, they represented a profound change. Baca’s Downtown was not to be erased or packaged for tourists; it was to be incrementally rebuilt as a place where people might once again live, work, and gather.

This was also a political gamble. Figures like Pete Dinelli, who had made their careers treating Downtown as expendable, first as a containment zone for smut shops, later as skeptics of housing and transit, still had significant sway. To argue that Downtown deserved investment was to swim against decades of inertia and a deeply ingrained culture of sprawl. That Baca pushed these projects at all was a sign of political courage, however uneven the results (and he even got Dinelli to sign onto supporting the measure for a Downtown Performance Arts Center).

These uneven projects that set the stage for Downtown’s modest revival in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Without the Theater Block, there would have been no anchor for the Sunshine’s survival. Without the Alvarado, no civic gesture toward reconnection. Without Villa San Felipe, no precedent for housing. They were not miracles but they were a pivot, away from containment and spectacle, toward a philosophy of repair.

Downtown 2010 Plan: Blueprint for a Core

By the late 1990s, Downtown Albuquerque stood at a crossroads. The Festival Market had failed, the Sunshine Theater had survived, and the BetaWest towers had planted their pink pyramids on the skyline. Jim Baca’s administration had invested in projects that stitched fragments of life back into the core: the Theater Block, Villa San Felipe, and the Alvarado Transportation Center. But Downtown’s future was still unsettled, its fate caught between inertia and reinvestment.

The Downtown 2010 Plan, adopted in 1998, was the most comprehensive effort yet to give the core a future. Drafted with the Downtown Action Team,74 it was a ten-year blueprint for remaking Downtown not as spectacle, but as a working urban neighborhood.75

Its aims were ambitious for Albuquerque at the time: jump-starting significant new housing downtown (not just offices), re-establishing mixed-use activity along Central, Silver, and Gold, elevating arts and culture as civic anchors, and committing to streetscape, lighting, and infrastructure improvements to reverse the damage of mid-century renewal.

This shift represented more than a shopping list. It was a philosophical break from decades of treating Downtown as expendable. In the 1980s, councilors had openly argued it should serve as a containment zone for smut shops. Now, official city policy said the opposite: that Downtown was central to Albuquerque’s identity, and that repairing it was a public good.

Implementation was uneven. Some housing did arrive, loft conversions and apartments like Villa San Felipe establishing a toehold. Streetscape projects softened the hardest edges of the core. The Sunshine endured, the KiMo survived, and a small arts scene began to take shape. But the contradictions were real. Greyhound refused to move into the rebuilt Alvarado, leaving the city’s intermodal dream incomplete. Crime and the perception of disorder persisted. Vacant lots still pocked the landscape. And retail investment never reached the scale the plan imagined.

The success of the era was palpable. For a brief moment, Albuquerque began to honor its past by rebuilding the Alvarado not as a hotel but as a civic hub, acknowledging the wound of its demolition while trying to heal it. The plan also signaled a rare agreement across political lines: that Downtown mattered, and that strengthening it would benefit the entire city. For once, the core was treated as more than isolation area for vice or a stage set. It was acknowledged as the civic heart, the place that could hold the city together.

Even the gaps began to close. After years of resistance, Greyhound eventually moved into the rebuilt Alvarado, completing the multimodal hub that had once seemed destined to remain half-realized. The city’s ailing transit system, SunTrans, notorious for poor service, safety issues, and failing equipment, was reborn as ABQ RIDE, its new logo modeled after the Alvarado’s Spanish Revival façade — a symbolic admission that transit, like Downtown itself, required not just repair but reinvention.76

In 2004, the city launched its first Rapid Ride line,77 a bold experiment in higher-quality bus service that ran along Central Avenue to Wyoming and Uptown. For the first time in decades, Albuquerque had a corridor where transit was fast, frequent, and reliable. The Rapid Ride would be a prototype of what real rapid transit might look like. The line was popular from the start, connecting Downtown to neighborhoods and jobs in a way that ordinary bus service never had.

In the background, the state was looking further ahead. Rail studies laid the groundwork for what would become the Rail Runner,78 linking Albuquerque not just to its suburbs but to Santa Fe, the state capital. The Alvarado Transportation Center was no longer just a gesture toward a demolished hotel; it was becoming a hub in a regional system.

By the mid-2000s, with new housing on the horizon, entertainment venues opening, and a growing emphasis on transit and regional links, Albuquerque seemed poised to think of itself, at last, as a true metropolis. Not simply a city among mesas, but New Mexico’s city, reclaiming a mantle it had not worn with confidence since the days when Clyde Tingley presided over the council.

For a brief moment, the optimism was undeniable. The wounds of urban renewal were not healed, but they were acknowledged. The city had begun to honor its past through projects like the Alvarado, even as it gestured toward a more urban future. And while the momentum would falter in the years ahead, the Downtown 2010 era proved that Albuquerque could, when it chose, see itself whole.

The era did not last. By the mid-2000s, momentum faltered. Private investment turned back to the suburbs, sector plans and sprawl regained dominance, and Downtown’s fragile coalition dissolved. Yet the memory of that short window still shapes Albuquerque today. The 2010 Plan demonstrated what was possible when leaders, residents, and businesses chose optimism over abandonment. And tellingly, Downtown leaders are once again reconstructing this framework, revisiting the same principles of housing, walkability, and cultural anchors.

Albuquerque has always had the capacity to reinvest in its core. When it does, the results are visible and shared. The challenge is (and will be) sustaining that optimism long enough to carry it forward.

Barelas Stakes Its Claim In The Core

Yet plans and policies only mattered insofar as they touched real neighborhoods, and nowhere was that more visible than in Barelas. Just south of the core, it had absorbed the brunt of renewal in the 1970s, whole blocks cleared until only fragments remained. By the late 1990s, the neighborhood was once again at the center of debate; this time over the siting of the National Hispanic Cultural Center. In Barelas, the abstract promises of the 2010 Plan collided with lived history: demolition and survival, cultural ambition and defiance, scars of displacement alongside dreams of renewal. To understand what Downtown’s revival meant in practice, you had to look not just at towers and plazas, but at the streets of Barelas.

If Martineztown spent the late twentieth century wrestling with its identity — resisting some redevelopment, denying its connection to the core — Barelas took a different tack. For all the wounds urban renewal had inflicted on its streets, and despite the poverty and disinvestment that lingered, Barelas never disavowed its proximity to Downtown. It claimed it.

South Barelas, in particular, had been nearly erased in the late 1970s, targeted by the city for wholesale clearance under urban renewal. Families who had lived there for generations accepted “ridiculous offers” for their homes because they believed condemnation was inevitable. Adela Martinez, who refused, remembered her neighbors leaving in fear: “People actually thought the city could condemn their homes and they wouldn’t get a penny for them. That’s why they took the ridiculous offers they were getting. I know people who took $15,000 for their homes. I know people who still don’t have homes because of that.”79 For decades, she lived as the last resident on her block, her green-stucco home surrounded by vacant lots and commercial buildings.

It was there, in the late 1990s, that the state chose to build the National Hispanic Cultural Center (NHCC). For Martinez, it was another violation. “We never needed a shrine to tell us who we were,” she told the Journal in 1999.80 “We just knew.” For Senator Manny Aragon and cultural leaders, it was something else: a progressive step toward honoring Hispanic heritage and building a cultural institution that could stand alongside Barelas’ historic significance as a railroad and Camino Real hub. The battle was bitter — Martinez refused repeated offers to sell, including one for $119,500,81 and forced architects to redraw their plans to literally build the center around her home.82

Her resistance made the NHCC not just a cultural amenity, but a narrative. On one hand, it embodied the scars of renewal: a woman whose neighbors had been displaced, refusing to leave even when encircled by parking lots and amphitheaters. On the other, it showed a new willingness to invest in Barelas as a place of cultural significance. Edward Lujan of the Center’s Foundation insisted: “The center will benefit everyone. The center will attract attention. We’re seeing it as enhancing our culture.”83

At the same time, the neighborhood was undertaking its own quieter revival. The Tribune reported in 1996 on new homes rising on Bazan Court, a streetscape project for Fourth Street, and residents determined to “see their rebirth through.”84 Families like Miguel Horta and Jacqueline Castro, who thought they would have to leave for the West Side to afford a new home, instead found one in Barelas: “We thought we’d have to move… Now we will live almost within walking distance of our parents and grandparents.” The reopening of the Red Ball Café, immortalized by its Wimpy burger, gave the neighborhood both nostalgia and pride. Entrepreneurs like Jim Chavez took on the challenge: “This gives me a chance to put something back into the place I was born.”85

These investments mattered not just because they improved the neighborhood, but because they reinforced Barelas’ historic identity as a place of movement. The Camino Real, Route 66, and the Santa Fe Railroad had all coursed through its geography. The railroad shops, once employing over a thousand, were remembered as a “cathedral” of working-class life. Even as those institutions vanished or moved, Barelas remained tied to the city’s arteries. Unlike Martineztown, which tried to wall itself off (or, was walled off by outside forces), Barelas leaned into its role as a neighborhood linked inherently to circulation, migration, and exchange.

In this way, Barelas embodied both the contradictions and the hopes of Albuquerque’s 1990s renaissance. Grand civic projects like the NHCC coexisted with grassroots initiatives like affordable housing. The memory of demolition and disinvestment lived alongside new pride and reinvestment. Barelas was not “saved” by any one project, but by its people. And in enduring, it showed that Downtown was not only a matter of towers and plazas, but of neighborhoods that refused to disappear and embraced adaptation, change, and even, or especially, growth. They showed that “neighborhood character,” that old, racist term, was actually about the people that inhabit and make a place. Not about a nostalgia that can’t be recreated or mantra to keep people out.